Why you should always be sceptical of new funds promising miracle returns

Many market-beating strategies could be an illusion caused by the constant search for new ways to sell funds, says Cris Sholto Heaton.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

There’s a well-known problem in many fields of research where findings from one group of researchers can’t be confirmed by others who try to repeat the same experiment. Areas such as psychology, sociology and medicine are especially prone to this – one study found that only half of a set of psychology experiments could be reproduced, with a number of high-profile and influential findings turning out to be false.

This isn’t necessarily because of fraud on the part of the original researchers; patterns will often emerge by pure chance if you crunch a set of data for long enough, and the incentive for researchers to keep crunching until this happens means that they can end up with a finding that appear to be statistically significant but is really just noise.

In theory, investing should have less of a problem than most fields. Ideas for strategies to deliver better performance will always be tested in the real world. If too many are failing, it should be obvious. Yet that assumption may be too optimistic, according to Campbell Harvey, professor of finance at Duke University in the US. In an interview with the Financial Times, he suggests that at least half of 400 market-beating strategies published in reputable financial journals can’t be replicated.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Results in the real world

Some researchers come to the same conclusion – a paper by Kewei Hou, Chen Xue and Lu Zhang (Replicating Anomalies) found that more than 80% of results they studied could not be reproduced. Others dispute it: Is There a Replication Crisis in Finance? by Theis Ingerslev Jensen, Bryan Kelly and Lasse Heje Pedersen reckons most findings they review appear to hold up. The debate remains live on an academic level, but there is some practical evidence to support it.

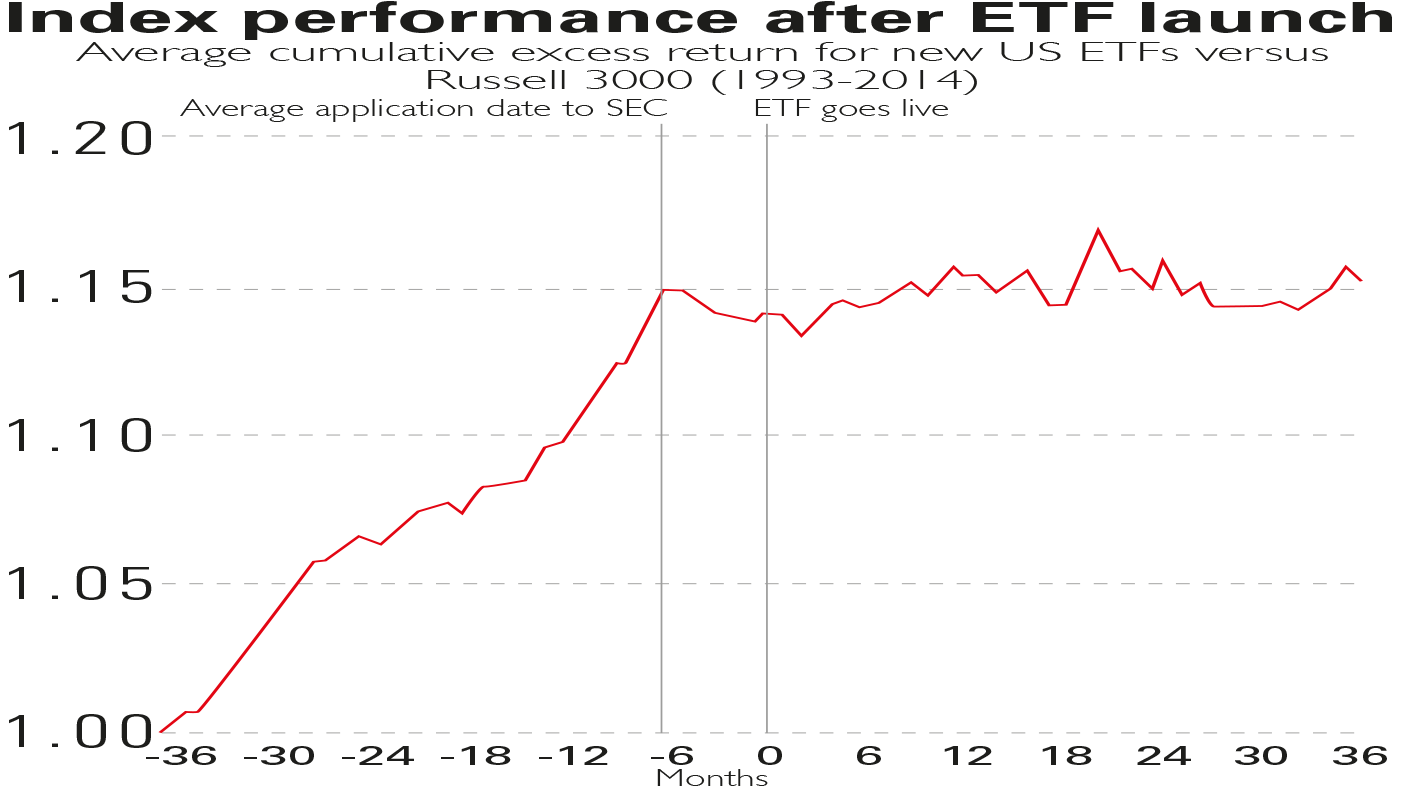

You’ve probably seen asset managers proudly launch new funds that have a great record in backtesting, but fail to deliver in the real world (this is true of many smart beta ETFs – see below). The chart above – from Research Affiliates and reproduced in a recent paper by Harvey – shows the average performance of the indices used for new US ETFs. On average, indexes strongly outperformed the market in the 36 months before ETF launches – but that outperformance tended to disappear over the next three years.

In some cases, the successful strategy will have been a statistical illusion from cherry picking or twisting data. Sometimes real-world transaction costs eat away at theoretical excess returns. Or the wider market environment may change (value strategies had a long record of success but have done badly for the past decade). Regardless of the reasons, investors should always be sceptical of new products promising miracle returns.

I wish I knew what smart beta was, but I’m too embarrassed to ask

Finance theory divides investment returns into two parts. Alpha is the value added through the decisions made by you (or the manager of the fund you hold). Beta is the return that results from the overall market.

Assume that a portfolio of investments goes up by 15% while the overall market rises 10%. In this case, beta is 10% and alpha is 5% (15%–10%). In reality, the calculation is a bit more complicated because it depends on whether the type of stocks in the portfolio would be expected to fluctuate more than the overall market, but this demonstrates the idea. Beta is what you get from simply being invested in the market (ie, what a passive index investor gets); alpha is what an investor gains or loses from active investment management.

Smart beta strategies lie between active and passive investing. A smart beta fund tracks an index, but with that index constructed differently to a traditional stockmarket index. Instead of weighting securities by size, a smart beta index selects or weights according to characteristics that may make them more likely to outperform the wider market. Common characteristics (often called factors) include variations on size (historically, small stocks tend to outperform larger ones on average); value (stocks that seemed cheap on metrics such as price/earnings or price/book have tended to outperform expensive ones); volatility (less volatile stocks have tended to do better); momentum (stocks that are rising strongly may be more likely to keep rising); and quality (profitable, efficient business with less debt have tended to beat weaker ones).

Advocates of smart beta say that it can deliver higher returns than passive investing in a cheaper and more systematic way than active investing. This makes sense in principle, but depends on the continued success of the factors chosen for the smart beta strategy. There can be no certainty that a factor that worked in the past will keep doing so.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?