Why the Yale model of investment teaches us the wrong lessons

The “Yale model” of investment sparked a boom in alternative assets, yet its mastermind gave very different investing advice.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The lesson that many investors take from the success of David Swensen (see below) is that they can improve their returns by ditching traditional stocks and bonds for alternative investments (see bottom). Nothing is further from the truth. Plenty of endowments, pension funds and other institutions have failed in their attempt to emulate the Yale model, and most private investors are likely to do even worse if they try to copy Swensen’s approach.

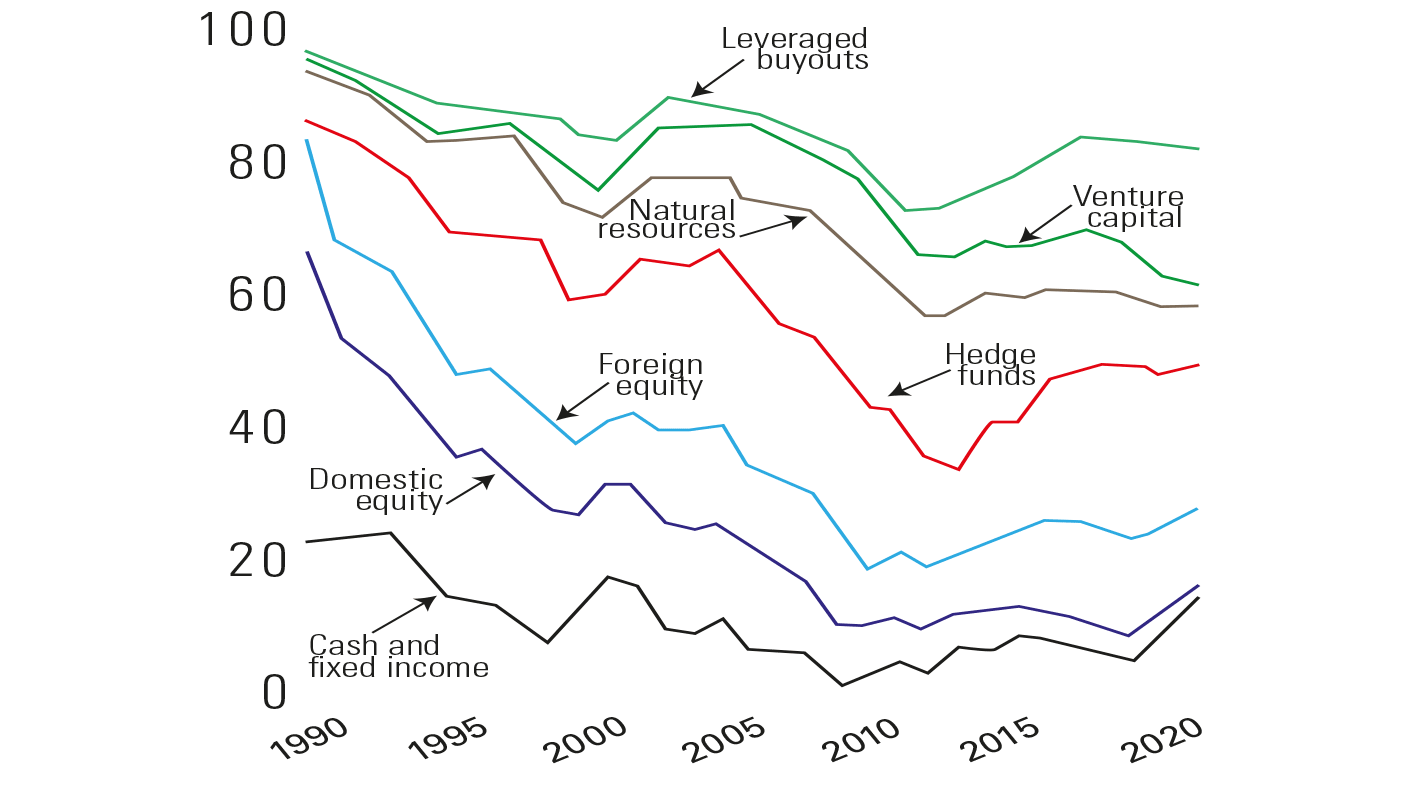

The main reason hides in plain sight in Yale’s own analysis of its returns. Only 40% of its outperformance is due to asset allocation; the rest is due to the manager’s selection. Yale has a skilled team and a rigorous process dedicated to finding the best managers – an edge that is much harder to duplicate than simply copying its current asset allocation (see chart). What’s more, Yale’s clout and network gives it access to high-performing funds that aren’t available to many institutions, let alone individuals.

A strong reason to keep it simple

Some investors will assume that even if they can’t earn the 60% of outperformance that came from top managers, they can still get the 40% that comes from more exotic asset allocation. But in alternative assets, it rarely works that way. Performance is highly skewed: a small number of managers do very well, while a large number do rather poorly. The underperformance from a pool of inferior managers will often wipe out all the theoretical outperformance you’d expect from the asset class, leaving you worse off than if you’d kept it simple.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

That’s why Swensen recommends the opposite for private investors in his book Unconventional Success. This was published in 2005 and the investment business has moved on in a few respects, but the message remains relevant.

Investors should build a portfolio around six core asset classes that have distinctively different properties: domestic shares, international shares, emerging market shares, real estate investment trusts, government bonds and index-linked government bonds. And they should implement this through cheap index funds.

Swensen argues against corporate bonds (they “serve no valuable portfolio role”). Hedge funds, venture capital and leveraged buyouts “belong only in the portfolios of the handful of investors with the resources and fortitude to pursue and maintain a high-quality active management programme”. Many investors will disagree on some points (they may want to hold gold, they may think active funds can play a role), but the warning to avoid the temptation of alternative investments is one to heed.

David Swensen: the “pioneer who reshaped investing”

David Swensen, who died last week, was a “pioneer who reshaped investing” in his role as the head of the Yale endowment fund, says Robin Wigglesworth in the Financial Times. While he “never commanded the fame of Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch or Jack Bogle” with the wider investing public, “among industry insiders, he is widely considered in their rank”.

When Swensen took charge of the fund in 1985, it was worth $1.3bn. It went on to return an average of 12.4% per year over the past three decades and is now worth $31bn (the rate of return is greater than the growth in the fund because some of the endowment is spent each year – it contributes more than a third of the university’s budget). But it was the way that he earned those returns – rather than the size of them – that made him so influential among other institutional investors.

“Swensen built his career with alternative investments,” says John Rekenthaler on Morningstar. When he took over the fund, it was much like any endowment at the time, with two-thirds of its assets in equities (mostly US stocks) and the bulk of the rest in bonds and cash. “Swensen had other ideas. In time, he transformed the fund completely”. Today, most of the fund is in alternative investment strategies: hedge funds, leveraged buyouts and venture capital. That approach was much copied by those who tried to follow Yale, yet few succeeded. “His brilliance lay not in showing others the way, but rather in accomplishing what they could not.”

I wish I knew what alternatives were, but I’m too embarrassed to ask

Alternative investments – often just referred to as alternatives – is a broad term for anything that does not fall into one of the conventional asset classes of listed stocks, bonds and cash.

Real estate is the most widely held of these. Listed real estate investment trusts (Reits) are classed as conventional investments, but direct investment in real estate is not, because this represents an interest in a specific property that can’t be bought or sold quickly. Assets such as timberland or other natural resources are treated in a similar way: a timber Reit or shares in an oil firm are a conventional investment, owning the underlying assets is an alternative investment.

Other common alternatives include funds invested in assets that are not publicly traded. This includes private-equity funds that invest in unlisted businesses (such as leveraged buyout funds, which often buy listed firms and take them private, using a substantial amount of debt to fund the deal), as well as venture capital (which invests in early stage growth companies). Funds that invest in distressed, illiquid or private debt also fit in the alternatives category.

While many alternative investments are unlisted or highly illiquid, the category also includes funds that invest in listed, liquid securities if they rely heavily on tools such as short-selling, leverage or derivatives. These are typically referred to as hedge funds and cover a wide range of strategies, from absolute return funds (aiming to make positive returns regardless of market trends, typically through use of derivatives) to global macro funds (making big bets on a range of assets based on an analysis of economic or political trends).

Established alternatives also include precious metals, such as gold. The inclusion of art, stamps and wine is more debatable, as not everybody would agree that these constitute investments – an argument that also now rages over cryptocurrencies.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?