The UK housing market is facing its biggest test in 70 years

Low-cost mortgages have inflated house prices and the housing market, but this trend is set to go into reverse as the cost of borrowing rises says Dominic Frisby.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Despite being built of bricks, a house is, in many ways, a financial asset. This is because, for the most part, we use finance - debt - to buy real estate. And debt has been propping up the UK housing market since the 1950s.

The influence of mortgages on the housing market

Mortgages, aka “death grip”, have been around for hundreds of years. Indeed debt has been around since before human beings settled on the fertile plains between the Tigris and the Euphrates. But mortgages in the UK only hit the mainstream in the 20th century. First, after WWI, following Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s 1918 promise to build “homes fit for heroes”, and then, probably more so, in the 1950s as the Tory government reduced Stamp Duty and lent money to building societies as part of its pledge to create a “property-owning democracy”. In the 1950s and 60s home ownership went from below 30% to above 60%.

On the one hand, the mortgage enabled many people to get on the housing ladder in the first place. The financing will have enabled more properties to be built. But on the other hand, by introducing debt into a market, you introduce more money into that market and the consequence is usually higher prices (See student loans for more details). If house prices were determined only by the amount of available cash, they would be lower and more in line with earnings.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

But house prices are determined by the amount of debt that is available, which in turn is determined by the cost of money (interest rates), general risk appetite and so on. That is why prices are now so out of kilter with earnings. Once upon a time, and not so long ago, house prices were three times earnings. Now in London, they are north of 10 times.

It’s credit, not supply that matters

The widely accepted view is that houses are unaffordable because we do not build enough and this has led to a shortage of supply. The stats I would always call on to counter this argument are that between 1997 and 2007 the housing stock grew by 10%, but the population only grew by 5%.

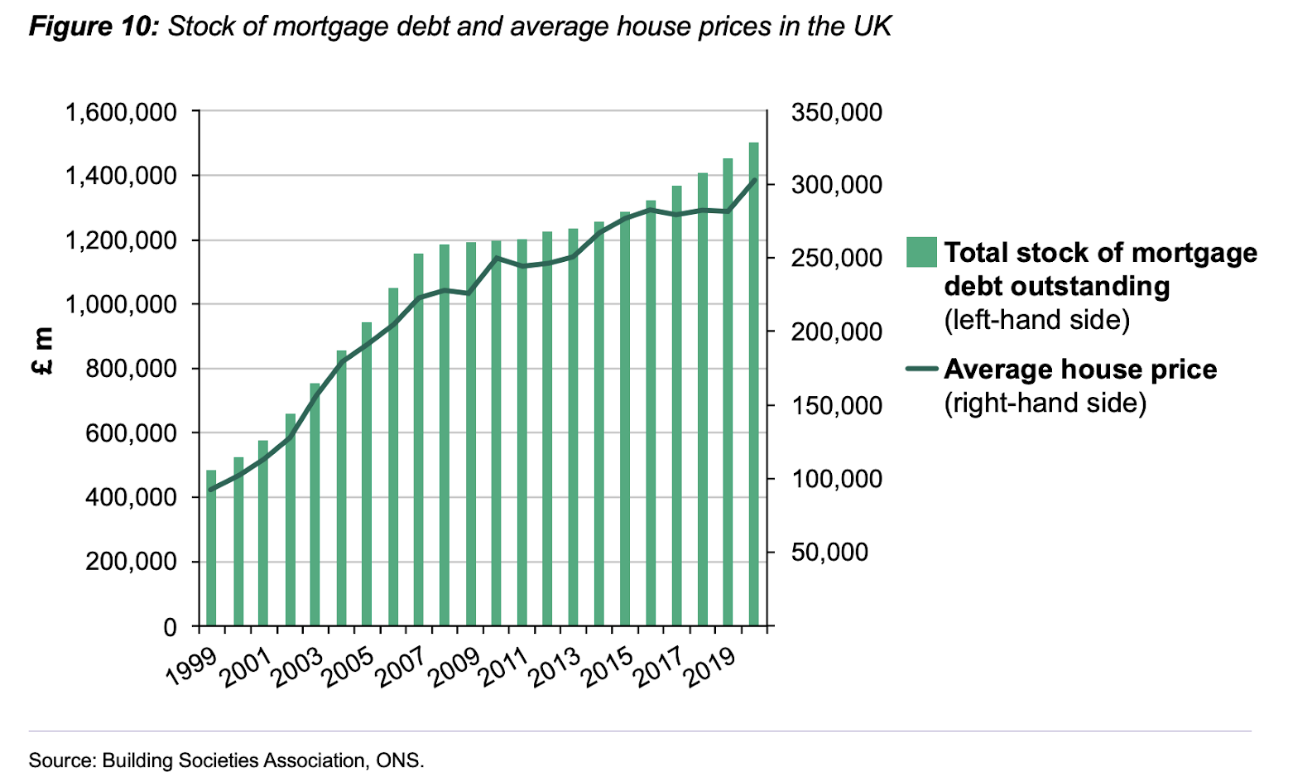

If house prices were a function of supply and demand, they should have fallen slightly over this period. They didn’t. They rose by more than 300%. The cause of house price rises is the unrestrained supply of something else: money. Mortgage lending over the same period went up by 370%.

Some might argue those numbers are out of date, but the latest numbers tell a similar story. In the ten years to 2021, the housing stock in England and Wales has grown by just above 6%. The population by a similar amount - 6.5% in England and quite a bit less - 1.4% - in Wales.

But average UK house prices over the same period went from £167,000 to £270,000 (more in England). Mortgage lending, meanwhile, more than doubled (from £153bn to £316bn) over the same period. The relationship between money supply, aka credit, and house prices is obvious.

Research by thinktank Positive Money shows that over 50% of the money created by banks when they lend now goes into mortgages. All that newly created money going into a market where supply is constrained by planning laws will inevitably push up prices.

These two charts from Positive Money illustrate the relationship between credit creation and house prices.

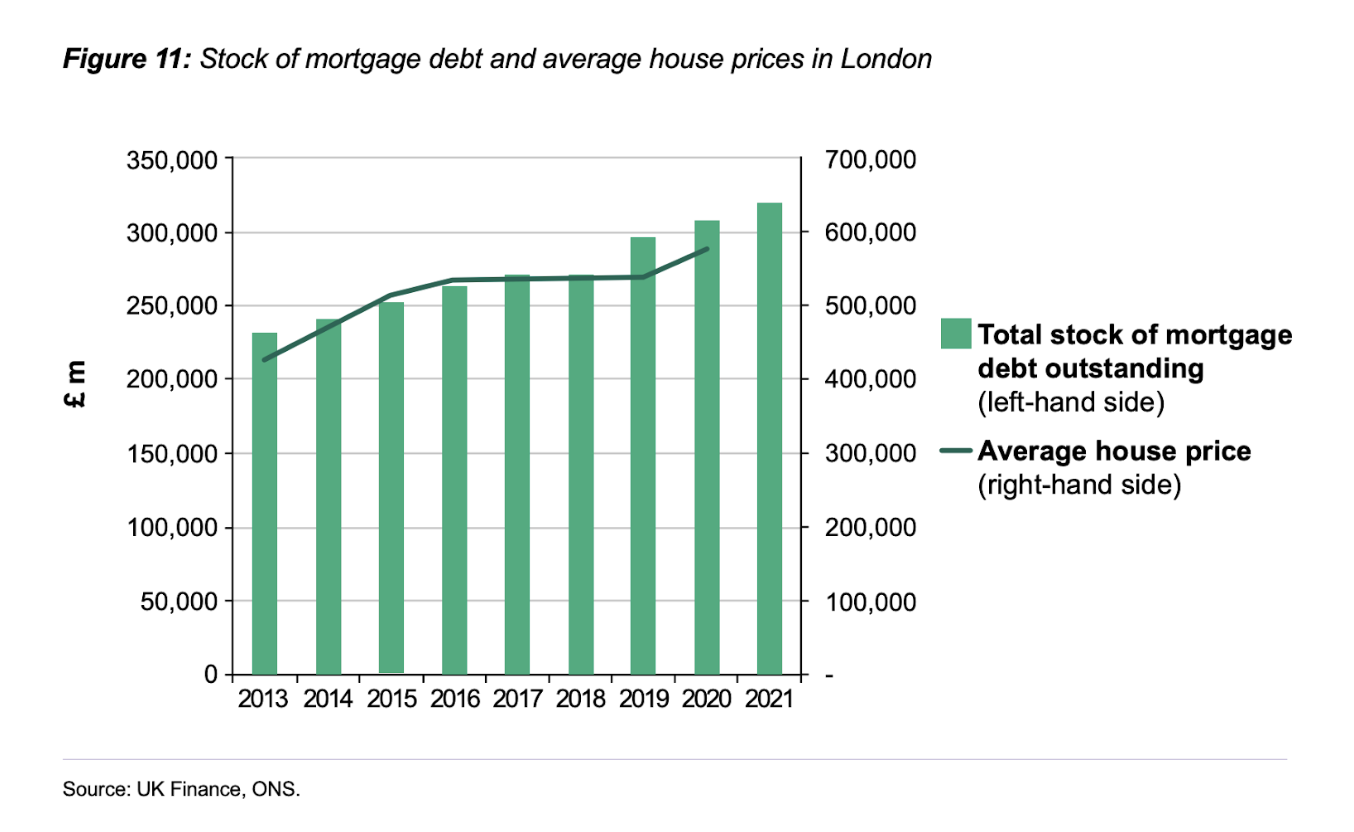

Here is London.

I’m not saying population growth doesn’t affect house prices. It does. But not as much as money or credit supply.

Even the Telegraph admitted this yesterday, albeit accidentally, saying: “The jump in house price cuts corresponds directly with a doubling of mortgage rates”.

The Bank of England has allowed the bubble to grow

The Bank of England does not factor money supply or house prices into its measures of inflation. It only includes a basket of consumer goods and services. These are prone to the deflationary forces of globalisation and increased productivity: that is to say, the shirt on your back has got a lot cheaper because it is now made in Bangladesh where labour is a lot cheaper than it was in Manchester, or wherever it was made a few decades ago.

Thus, the Bank has been able to say inflation is low for decades, it has kept interest rates too low for decades, money has been too cheap for decades, people have borrowed for decades and house prices have risen for decades.

Of late, we have hit something of a deflationary limit, albeit a temporary one. First, Covid hit supply chains and that has pushed up prices. Second, the trend is towards more not less government intervention, regulation and taxation, which also put upwards pressure on prices. Third, where does the world now go to find cheaper labour than in Bangladesh and China? Africa, maybe, or machines. Still, for the time being, we have hit peak cheap labour.

Thus has inflation spread, even by the Bank’s measures, and it is forced to raise interest rates. Rising rates push up the cost of borrowing. Many that have borrowed can no longer service their debts, and so look to reduce their debts or offload the assets they have borrowed against. This puts selling pressure on the market.

Rising rates reduce people’s appetite to borrow, the amount they can afford to borrow and banks’ willingness to lend. This takes buying pressure out of the market.

The result is the panic we now have in the housing market. Falling prices, bearish sentiment and more. A third of all listed homes are now discounted.

But, at 5%, the Bank of England base rate is still too low. Its own measures say inflation is 8.7%. Truflation has it at 11%. If you can borrow at 6%, in a way you’re making 5%, though few will see it like that.

What happens if rates go to 8.7% or 11%? It’s not like this hasn’t happened before.

I’m now 53. I’ve watched and been dumbfounded by the UK property market for too long. It is awful what it has done to this country, in my view, pricing out an entire generation, reducing family size and all the rest of it. For years every other government policy, it seems, is aimed at propping up the market, rather than letting it correct. That makes me reluctant to go all-out-bear in the way that many have done and call for 35% corrections in the housing market.

Time bombs in the housing market

However, there are two ticking time bombs.

First, if the Bank really does lose control of inflation and we get some kind of currency crisis. This would tie in with my cycle, Frisby’s Flux, which suggests we could see lows in sterling next year.

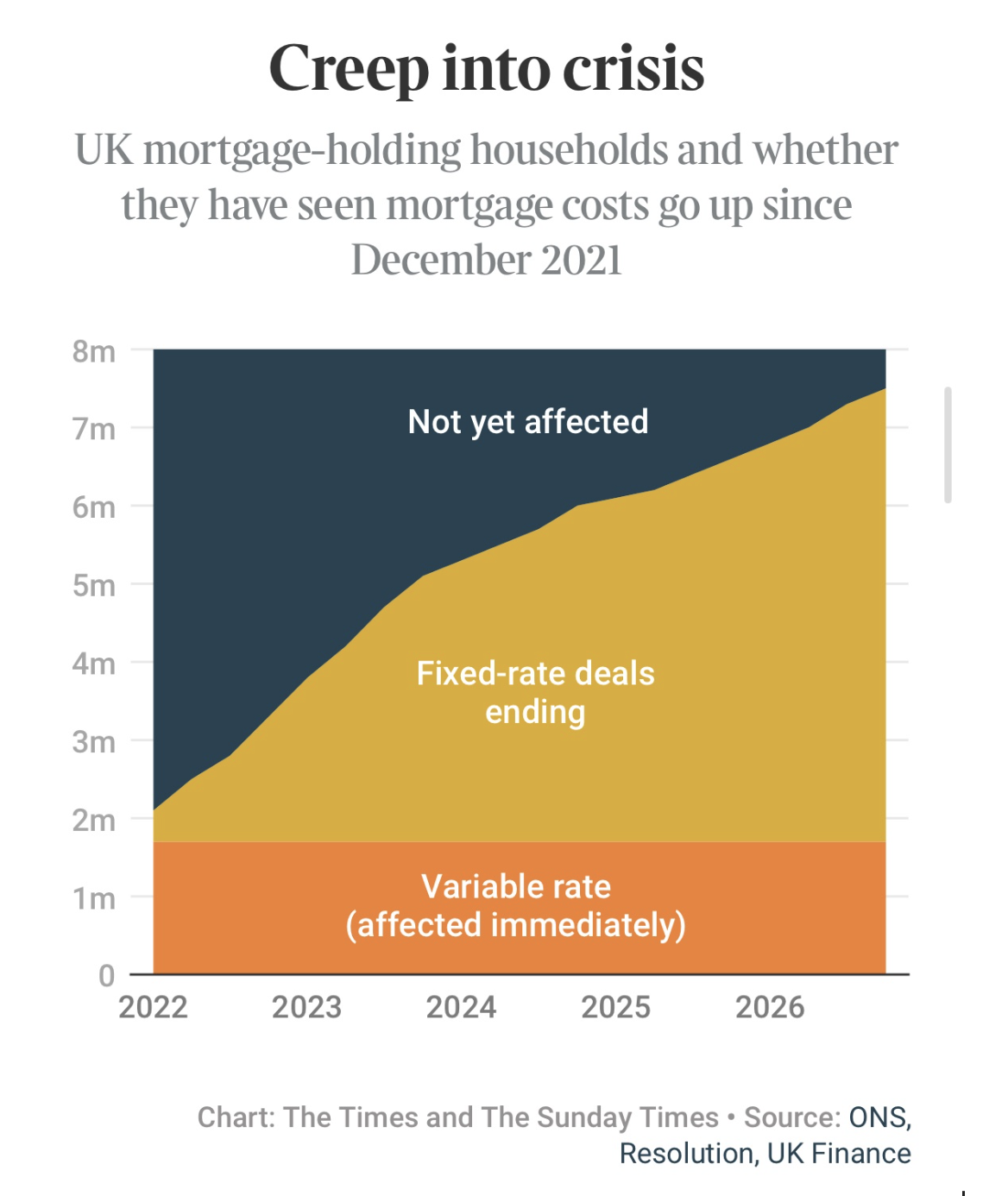

Second, the sheer number of fixed deals that are coming up for renewal in the next couple of years. This will see something in the region of two million households at least faced with mortgage repayments at least double the level they were when the original deal was taken out (see chart).

Many are not going to be able to meet those repayments. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) says 57% of UK fixed-rate mortgages were fixed below 2%. Forced sellers will quickly drive down prices.

The government will no doubt find ways to prop up the market. It knows this is coming. But housing markets move slowly, and I think houses almost certainly get cheaper before they get more expensive again. If you are looking to buy a home, unless it’s really urgent, I would find an excuse to wait.

This August Dominic will be performing one of “his lectures with funny bits” at the Edinburgh Fringe, at Panmure House, the room in which Adam Smith wrote Wealth of Nations. This one is about gold. You can get tickets here.

https://tickets.edfringe.com/whats-on/dominic-frisby-gold

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?

-

Look beyond familiar stockmarkets for reliable returns in rough times

Look beyond familiar stockmarkets for reliable returns in rough timesTips A professional investor tells us where he’d put his money. This week: Giles Parkinson, managing director of global funds at Close Brothers Asset Management.

-

Renters’ reform bill: what does it mean for landlords and tenants?

Renters’ reform bill: what does it mean for landlords and tenants?News The Renters’ Reform Bill, which promises an overhaul of the private rented sector, is currently being discussed by parliament. We look into what it could mean for tenants and landlords.

-

How to invest as we move to a hydrogen economy

How to invest as we move to a hydrogen economyCover Story The government has started to roll out its plans for switching us over from fossil fuels to hydrogen and renewable energy. Should investors buy in? Stuart Watkins reports.

-

A Canadian fund for the cautious income investor

A Canadian fund for the cautious income investorTips This investment trust offers a reassuringly boring way to navigate any imminent stockmarket volatility