Solar investing: is it too risky?

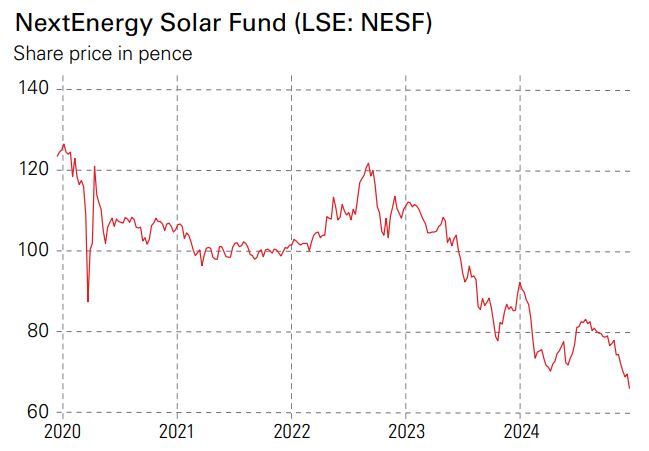

NextEnergy Solar Fund’s steep discount reflects doubts about high debts and the sustainability of its dividend. What does it mean for solar investors?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The UK has one of the most mature solar markets in the world with around 16GW currently deployed across the country. The government has a target to quadruple this to 70GW by 2035, illustrating strong support for solar as a source of low-carbon power and energy security. The latter has become a priority following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

What challenges are facing the solar industry?

Although solar power is a cheap source of energy when the sun is shining, the price that generators receive is often tied to the natural gas price. This means that renewable-energy companies benefited when the price of gas more than doubled from the start of 2022 to August of that year, following the invasion of Ukraine. However, since then the gas price has returned to close to its long-term average, and shares in the renewables firms have slumped.

NextEnergy Solar Fund (LSE: NESF) is one of the hardest hit, down by 40%. It trades on a forecast dividend yield of 12% and a 30% discount to its latest net asset value (NAV). Presumably, due to that yield, NESF has become the most-bought investment trust on platforms such as Hargreaves Lansdown, AJ Bell and Interactive Investor.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

A yield this high signals that there are risks. One reason for NESF’s low valuation could be its debt burden: this stood at £533 million as of September 2024, which is around 1.3 times its market capitalisation.

Management says that its weighted average cost of debt is 4.9%. Around 70% of the debt is fixed rate, including £200 million of preference shares issued in November 2018 and August 2019. These pay a fixed dividend of 4.75% and there’s no requirement to redeem them (instead they can convert into equity from 1 April 2036). The remaining £333 million debt consists of long-term interest rate hedged debt of £156 million and £153 million revolving credit facility (RCF) on a floating rate. This £333 million of debt will need to be repaid, either from cash flow generated by the solar panels or by selling off assets.

Management chooses not to show the entire £26 million interest costs from this debt running through a consolidated income statement. Similarly, it reports £1.14 billion of invested capital, yet total assets on the balance sheet are well below that level, at £771 million. The reason for the divergence is that management report as an investment entity on a non-consolidated basis. The company then makes investments in solar panels through holding companies and special purpose vehicles, which are off the balance sheet.

So we have fair-value accounting, a share price at a discount to book value, a reliance on short-term funding (the RCF), the use of alternative performance measures, and worries over the sustainability of dividends. This will sound familiar to anyone who followed banks before the financial crisis.

Slow progress on sales

In April 2023, management announced a capital-recycling programme, intending to sell five subsidy-free UK solar assets with 246MW of capacity. The proceeds would go to paying down debt, buying back shares and investing in battery-storage facilities.

NESF completed phase I of the divestment in November 2023, selling the ready-to-build Hatherden solar project with 60MW of capacity for just £15 million. In phase II and phase III, it sold the operational Whitecross (35.22MW) and Staughton (50MW) solar farms for £27 million and £30.3 million respectively.

NESF has invested £1.14 billion of capital to own 983MW of installed capacity. It is difficult with the information available to understand how much the value of a project should increase as it goes from ready-to-build to operational, but if one were to use the sale of 60MW of ready-to-build capacity for £15 million as a lowest bound, it would imply that the mark-to-market fair value of the group’s entire invested capital is closer to £300 million! To pay down the £333 million of debt at the valuation achieved for phase I, NESF would need to sell more than its installed capacity.

Fortunately, the subsequent deals have been better, even if both look to be surprisingly low valuations when we note by way of comparison that NESF paid €132 million (£110 million) for 35MW of installed capacity (the Solis portfolio) in Italy in December 2018.

Management is now more than halfway through the disposals, having sold 145MW of the 246MW target. Yet, based on the first-half figures, the debt burden remains stubbornly high.

Why is NESF trading at a steep discount to NAV?

Stockbroker Cavendish and renewable-energy specialists Longspur Capital have both published “sponsored research” (ie, the company pays for it) on NESF. Yet it’s not obvious from reading this material – which obviously aims to give the subject a chance to present its investment case clearly – why NESF is trading at a 30% discount to NAV, or what has caused the shares to fall 20% since the summer, when the gas price has risen sharply.

Still, there are a couple of helpful tailwinds. First, interest rates seem to have peaked with the Bank of England making two cuts. Secondly, gas for delivery next summer is being priced at a record premium to winter 2025/2026. Around half of NESF’s revenues come from inflation-linked government-backed subsidies, but it also locks in prices with a rolling three-year hedging programme. So rising prices should help support medium-term cash flows to maintain the dividend, and could also mean better prices on the remaining phases of the asset disposals.

Management said a few weeks ago that investors have sufficient information to calculate if the dividend is sustainable. That claim seems tenuous. The board has set a target dividend of 8.43p for the year ending in March, but cover is expected to decline to 1.1, down from 1.4 two years ago. The lack of consolidated reporting means it is hard to compare fair value accounting assumptions with the reality of cash flow. I hold the stock while feeling that a yield above 12% suggests a dividend cut is probable, but not inevitable.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Bruce is a self-invested, low-frequency, buy-and-hold investor focused on quality. A former equity analyst, specialising in UK banks, Bruce now writes for MoneyWeek and Sharepad. He also does his own investing, and enjoy beach volleyball in my spare time. Bruce co-hosts the Investors' Roundtable Podcast with Roland Head, Mark Simpson and Maynard Paton.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton