A strange calm in credit

Corporate bond markets remain remarkably relaxed, with yields that offer little compensation for risks

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Investors are nervous. There are few other ways to read the latest gains in gold – above $3,650 per ounce for the first time this week – or the big moves in long-dated government bonds. Yet some markets look remarkably unperturbed.

Take credit spreads – the gap between the yield on government bonds and corporate debt – which tend to blow out at times of stress.

Spreads for US investment-grade bonds are instead at their tightest since 1998, barely 0.8 percentage points (pp) above the yield on comparable Treasuries. Eurozone investment grade bonds are similar; they have been tighter at times (eg, 2007 and 2018), but remain very low. Spreads for non-investment grade bonds (known as high-yield) are around 2.9pp, a bit higher than they were earlier this year in both the US and European markets. But they are still right at the bottom of their long-term range, and below the 4%-plus area they hit in April – which was not itself exceptionally high.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The growth of private credit

One theory holds that spreads are tight because government bonds are getting riskier and no longer offer a real “risk-free rate” to benchmark corporate bonds against. Some argue that top-grade corporate credit could trade on lower yields than governments (the spread on US AAA-rated bonds is around 0.3pp).

This feels like a stretch. The most likely escape route for governments is to have central banks buy bonds at low yields – a precedent set under quantitative easing. That is probably inflationary and inflation will hurt low-yield corporate bonds. If you expect this, you should demand higher yields, not settle for less.

Another argument with high yield, in particular, is that the corporate bond universe is of higher quality now. The growth of private credit – the hottest area in alternative assets over the past few years – means that lower-quality borrowers have migrated there to get more favourable terms. That has left the better borrowers in bonds. There is probably some truth in this, but spreads still look so tight that they don’t provide much compensation for risk.

Of course, tight spreads also explain why higher yields in private credit have proved so attractive. The challenge with private credit is that it is by definition less public, so it’s harder to have a clear picture of the market and how much risk investors are taking to earn, say, 200pp more yield from something much less liquid.

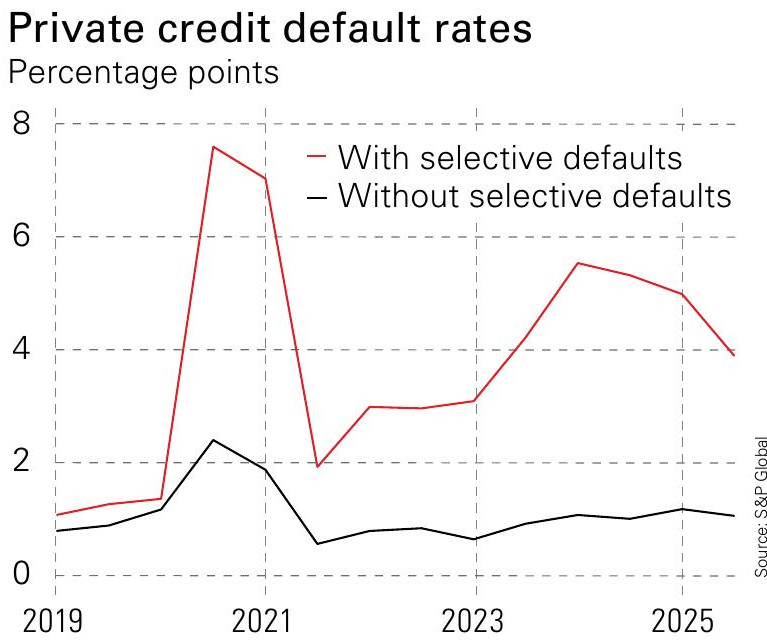

On the face of it, default rates remain low – around 1% according to a recent paper by ratings agency S&P Global. But this relies on a narrow definition of default and ignores selective defaults, such as converting cash interest into more debt, repayment holidays or extending debt maturities. Include those and defaults have been much higher, says S&P, despite the benign environment. Data from other analysts paints a similar picture. One has to figure there will be a reckoning here when the cycle turns, making low credit spreads in bonds a dangerous reason to reach further for higher yields in private credit.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?