Should you be worried about energy windfall tax proposals?

Calls have been growing for a windfall tax on UK oil and gas producers. It's a popular idea, but is it a good one? And what does it mean for investors in the UK's energy companies? Rupert Hargreaves explains.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

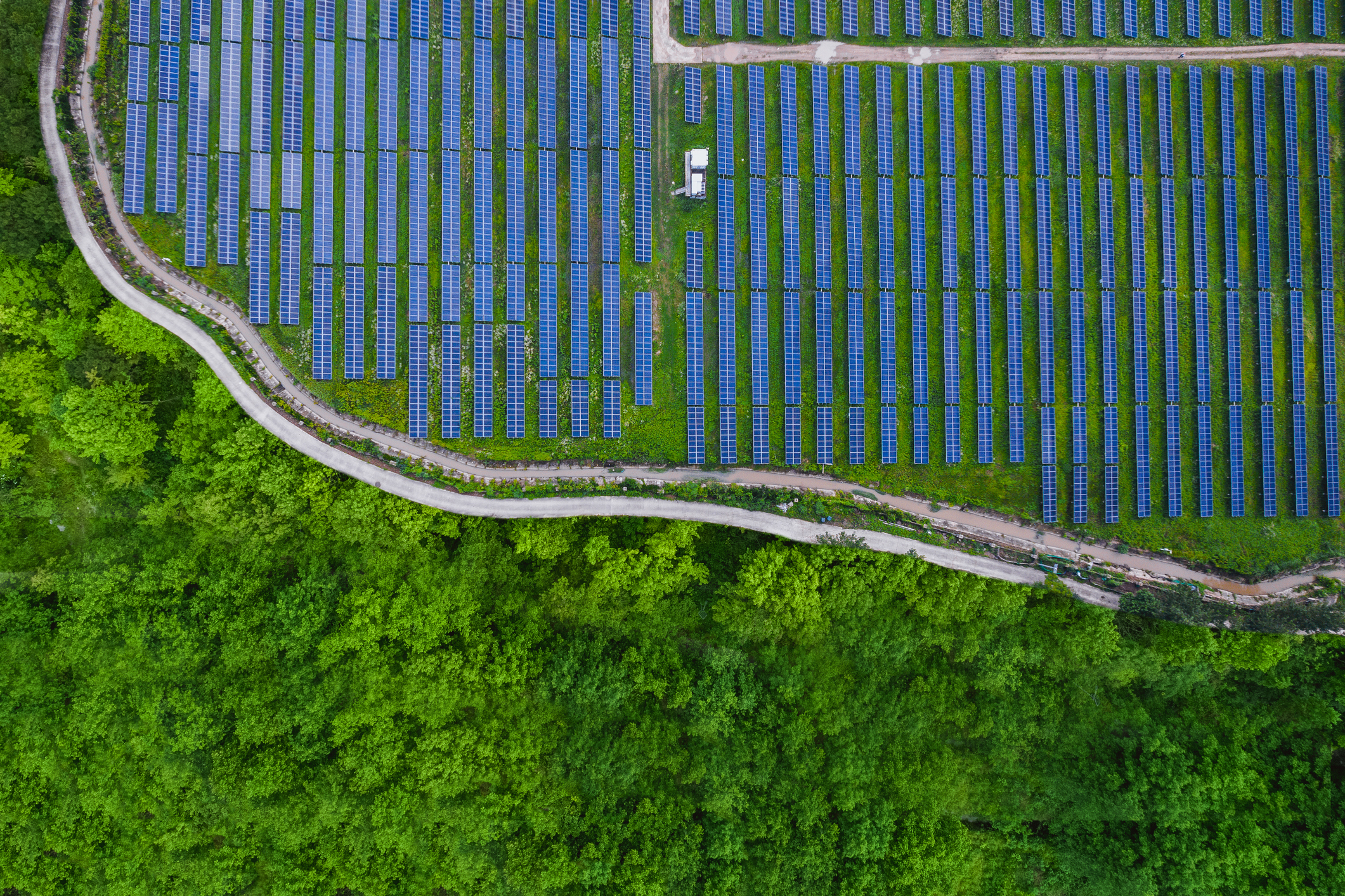

Calls have been growing for the government to impose a windfall tax on UK oil and gas producers to help ease the cost of living crisis. According to the Financial Times, Rishi Sunak may even go further and impose a windfall tax on more than £10bn of “excess” profits by electricity generators, including wind farm operators as well as hydrocarbon producers.

Such a tax would go well beyond initial proposals, and is likely to have a huge impact on the UK energy sector. While it might be popular politically, analysts have warned that a windfall tax could hurt investment and the UK’s international business reputation.

Unsurprisingly, the market has reacted pretty negatively to speculation that power generators such as SSE (LSE: SSE), Drax Group (LSE: DRX), Centrica (LSE: CNA), Greencoat Wind (LSE: UKW) and others might be dragged into the tax net. These companies have already laid out big spending plans for the next few years to help the UK meet its climate targets. Today’s windfall profits will help them meet these capital spending obligations; they won’t if they’re confiscated.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

How will a windfall tax hit corporate profits?

At this point, it’s hard to say what, if any, effect a new tax will have on the sector. The Labour Party estimates that a tax on North Sea oil producers would raise £2bn. Greenpeace UK claims the sector will earn windfall profits of £11.6bn this year, suggesting a tax rate of around 17%. A similar take on the £10bn of estimated excess profits of electricity generators suggests a bill of £1.7bn for the sector.

Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) has already estimated that UK oil and gas operators will pay £7.8bn in tax this year, a 20-fold increase in 12 months.

A one-off charge is likely to have the biggest effect on power generator Drax. According to Citi analysts it is “one of the most operationally geared to a fall in commodity prices and/or political intervention in the power sector.” Drax is the UK’s biggest producer of renewable power by output, although it was recently asked by the government to fire up some of its legacy coal power plants to “stabilise the power system during periods of stress”.

Last year adjusted earnings totalled £398m. This year management expects Drax to earn between £540m and £606m. Most green energy companies receive subsidies from the government to help fund the cost of developing renewable projects. These agreements generally fix the price these businesses can charge consumers, with any upside going back to the government.

Drax operates under a different agreement. It benefits from so-called “renewable obligation certificates,” which allow it to keep any upside. This is another reason the firm could be more exposed than most to a windfall tax.

It is also developing carbon capture technology in an effort to generate large-scale “negative emissions”. This year’s outsize profits will help the company fund these plans (carbon capture is notoriously expensive and complex to implement), but if they’re taken away, the company will have to find another source of cash. That could mean more debt or lower shareholder returns.

Of course, we won’t know which corporations will be hit the hardest until details of the plan are announced. Susannah Streeter at Hargreaves Lansdown believes that any windfall tax would be “linked to the amount of cash poured into ESG initiatives to power the energy transition” and “measures taken by companies to ease the burden of high bills for cash strapped customers”.

That indicates that businesses such as SSE, which is investing £12.5bn over the next five years to accelerate its net zero strategy, should get off relatively lightly (there’s also an argument to be made here that Drax could escape the worst as well as a result of its investments).

Big Oil could be sheltered from a one-off levy

There are bigger questions around how the tax would work in practice. Big oil companies such as Shell (LSE: SHEL) and BP (LSE: BP) are making vast profits, but mostly outside of the UK.

Shell paid no tax on its UK oil and gas production last year even though it earned $21bn in net income overall. BP expects to pay £1bn tax on its North Sea profits this year, while analysts are predicting an overall net income of £16bn, an equivalent tax rate of 6.3%. But international earnings would be very difficult to tax.

So how should investors react to this latest threat? The best solution may be to do nothing – yet. As the US investor Peter Lynch once said, “far more money has been lost by investors preparing for corrections, or trying to anticipate corrections, than has been lost in corrections themselves.”

We don’t know what the government will propose, nor do we know if it will actually go ahead with it. Indeed, the backlash from business has already been fierce, and nothing concrete has been proposed.

Moreover, any tax will only be on a percentage of profits. Unless the tax rate is 100% (which seems unlikely) companies will still earn a windfall from high energy prices. And as the government is working hard to encourage investment in renewable energy, there’s bound to be some loopholes in any proposed regime.

Ultimately, a windfall tax is unlikely to hit the long-term outlook for green organisations such as Greencoat UK Wind, which is one of the largest wind energy investors in the UK. A one-off tax is also unlikely to hurt Shell and BP significantly considering their international footprints.

On the other hand, North Sea producers such as Harbour Energy (LSE: HBR) seem more exposed to a UK producer tax, as does Drax, considering its position in the country’s electricity market.

But whatever course of action the government decides to take, it’s unlikely to significantly alter the long-term outlook for those companies with strong balance sheets, international diversification and green growth plans. I’d concentrate on these businesses not just today but for the next decade and beyond.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Rupert is the former deputy digital editor of MoneyWeek. He's an active investor and has always been fascinated by the world of business and investing. His style has been heavily influenced by US investors Warren Buffett and Philip Carret. He is always looking for high-quality growth opportunities trading at a reasonable price, preferring cash generative businesses with strong balance sheets over blue-sky growth stocks.

Rupert has written for many UK and international publications including the Motley Fool, Gurufocus and ValueWalk, aimed at a range of readers; from the first timers to experienced high-net-worth individuals. Rupert has also founded and managed several businesses, including the New York-based hedge fund newsletter, Hidden Value Stocks. He has written over 20 ebooks and appeared as an expert commentator on the BBC World Service.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Rishi Sunak: MoneyWeek Talks

Rishi Sunak: MoneyWeek TalksPodcast On the MoneyWeek Talks podcast, Rishi Sunak tells Kalpana Fitzpatrick that we need better numeracy skills to improve financial literacy and boost the economy.

-

We need a coherent and affordable plan for the transition to Net Zero

We need a coherent and affordable plan for the transition to Net ZeroEnergy analyst Clive Moffatt gives his views on the energy market and how to transition to Net Zero

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax