Why the food crisis could get worse

The invasion of Ukraine is one of several factors that have pushed up food prices. We can’t expect a return to normal in 2023. Investors should be wary of the consequences, says Frédéric Guirinec.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, the prices of agricultural commodities shot up. Wheat gained 59%, sunflower oil rose 30% and maize rose 23%. Both countries are major exporters of these crops, thanks to the belt of highly fertile chernozem (or “black earth”) that covers much of Ukraine and extends into Russia. Together, they accounted for 28% of globally-traded wheat, more than the US and Canada together, 29% of the barley, 15% of the maize and 75% of the sunflower oil.

Their share of global production is smaller, but as major exporters they are crucial in meeting international demand. There were widespread fears about the impact this would have on global food supplies and the risk of widespread shortages, especially when prices of other crops grown elsewhere began to soar at the same time. Yet since then, prices have fallen back significantly, often to pre-war levels. In wheat, for example, strong exports from Brazil, Canada and the US help plug the gap. Much of the discussion about a food crisis has been replaced by concerns about the energy crisis, at least in wealthier economies.

Yet the risks haven’t gone away. Many of the underlying factors that drove the surge in prices remain highly concerning. Some predate Russia’s invasion, others have been exacerbated by it. All point to a greater likelihood of volatile prices, food shortages and the dangers that they bring in the years ahead.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Rising insecurity

Food production has risen strongly in recent years. Global production in primary crops has risen by 52% since 2000, to 9.3 billion tonnes in 2020 (roughly half of that consists of staples such as wheat, rice and maize, plus sugar), according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). Food security was not really a source of concern in the Western world. Indeed, in some areas such as Europe, the focus was on limiting the impact of farming on polluting rivers and aquifers and adversely affecting the diversity of birds, insects and other wildlife. However, in other parts of the world, the situation was deteriorating. Droughts, wars and the pandemic mean that around 770 million people went hungry in 2021, the highest number for 15 years, according to the FAO.

Although agricultural commodity prices have fallen back since the start of the year, in most cases they remain significantly higher than they were two years ago. And higher costs for other inputs – most obviously energy – mean that the price of processed food stuffs has risen substantially. In fact, in many cases these are more significant. Food prices are driven by general inflation more than raw-material costs. Cocoa producers get less than 2% of the price of the chocolates we buy. Wheat represents 5%-7% of the cost of a baguette. You’re certainly already noticing the impact of that in your shopping basket, but it will be blunted by the fact that food is just a small proportion of most people’s spending in wealthy economies: food represents only the fifth-largest expenditure of UK households, at 11% of income after housing, recreation, energy and transport. (In 1957, it made up one-third of household expenses.)

However, for lower-income countries – and for those on low incomes in wealthier countries – the current situation is already severe. In many African countries, food accounts for 50%-60% of spending, and thus a 50% rise in the price of bread or cooking oil is completely unaffordable. Hence António Guterres, the UN secretary general, warned in May that in the coming months we may see “the spectre of a global food shortage” that could last for years.

The role of the energy crisis

Yet the outlook for next year could be even worse, partly because of energy costs. Natural gas is used to make nitrogen fertiliser, which is a crucial crop nutrient within modern farming. Higher gas prices mean higher fertiliser prices, which are up fourfold, and also lower supplies as European makers cut back in response to the exceptionally tight European gas market.

For example, Norway’s Yara International, one of the world’s largest fertiliser makers, began reducing ammonia production earlier this year and announced another round of cuts last month. It now says it’s using just 35% of its European ammonia capacity. CF Industries, the biggest UK firm, has paused production at its site in Billingham. In total, around 50% of Europe’s ammonia capacity is out of use, reckons industry researcher CRU.

While fertiliser makers can import ammonia – and distributors import finished fertiliser – that will still mean higher prices. The pressure on crop nutrients doesn’t stop there: the market in other fertilisers is also under pressure. Belarus and Russia are major exporters of potash (potassium) and phosphorus fertilisers, and so supplies from them have been disrupted by sanctions. All told, this is likely to affect how much farmers plant for next year and the types of crops they plant (they might shift to ones that require less fertiliser).

On top of that, there’s the wider impact of higher energy costs. Earlier this year, the National Farmers’ Union warned of a huge drop in crops that are grown in glasshouses in the UK – such as peppers, cucumbers and aubergines – because heating them had become too expensive. The wholesale price of chicken – also raised indoors in heated barns, and fed on wheat – has risen by around 50% in some situations. Another factor we are all too aware of this year is the climate.

Farmers have always moaned about the weather, but this year droughts from the US to France to China have hurt harvests. In my own fields in the south of Brittany the heat in early June scalded the wheat and yields have been mediocre at 55 quintals per hectare (five tonnes per hectare) instead of the usual 75, though the quality is satisfying. UK farmers also indicate mixed results, although nothing compared with the 40% drop in 2020, the worst harvests since 1981. The world may experience better conditions next year, but this summer is a reminder that climate change is a severe threat to our food security. And just as energy prices and fertiliser shortages will have an impact that continues into next year, so too will these droughts.

Pastures are not growing, so farmers are feeding cattle and other livestock on hay and silage that had been cut and set aside for their winter food. That potentially means greater pressure on supplies of other food stuffs later in the year when these supplies are exhausted.

No focus on security

On top of this, we can add politics: both misguided long-term aspirations and panicky short-term responses. Let’s take the former first, as it provides yet another example of why we’ve ended up in such a mess. In Europe, the focus of agricultural policy has long been on climate change and the environment, rather than food security. Farmers had been subsidised to limit production. Now, the reduction in subsidies, the level of taxation, the high investments required to respect new regulations, and the relentless inspections have combined with freer trade in agricultural products, and so European farmers struggle to be competitive with other countries that do not have such constraints and costs (while having to sell at highly volatile prices). Consequently, the number of farmers has reduced sharply over the last 30 years in Europe.

For a long time their traditions, inheritance and culture made farmers accept their fate, but as their children decided against going into the sector, farms consolidated. France reflects this trend the most. A farming powerhouse in the sixties – Europe’s common agricultural policy was agreed to compensate France for German industrial strength – it now produces less milk than Germany and is a net importer of food (excluding wine and spirits). This summer, French restaurants have even been running out of Dijon mustard because most mustard seeds are imported from Ukraine and Canada (where a heat wave last year ruined the crop).

The number of farms has fallen by 21% over the last decade and the number of dairy and meat farmers is expected to halve over the next decade as they are unable to generate enough income, according to Les Echos. Than there’s the recent drive to reduce pollution sharply. The most notable example of this is the Netherlands’ aim to reduce nitrogen emissions from livestock by forcing farmers to reduce the number of pigs, chickens and cows by about 30%.

The government estimates that 11,200 farms will have to close entirely and 17,600 significantly reduce their livestock. This has sparked widespread protests among Dutch farmers, but the wider problem is whether it will have any net benefits for the environment. Much food production is already offshored: for example, over half of chicken consumed in France is imported from Brazil and Ukraine. Often this means importing from countries where the protection of the environment is much weaker, or where animal welfare standards are lower: think of Brazil deforesting the Amazon or of beef production in the US and Canada.

Thus by reducing production, you can make your domestic industry look greener, but you are simply shifting the high cost to the environment and the economy elsewhere. At the same time, it drastically reduces your food security and makes your supply chains more complex and fragile. Thus the Dutch proposals look frankly reckless for a continent that is already struggling with the disaster created by being too dependent on Russia for energy, even setting aside the question of what it is supposed to achieve. Emissions are often arbitrary figures – what should be of concern are the dwindling numbers of insects, birds and overall wildlife. Previous policies led to the construction of factory farms – to redress this, farmers should be (and are) developing new ways of farming: ploughing less frequently, seeding new types of cultures sometimes solely to preserve the ground during winter from erosion and curbing the use of chemicals (pesticide, fungicide, fertiliser) to preserve the topsoil.

Promoting this is sensible. Consciously cutting food production when heading into a world in which food security is clearly going to become an ever-greater issue is not. The best that one can hope for is that the events of this year will lead to a change in thinking. In the aftermath of the invasion of Ukraine, French president Emmanuel Macron spoke of adapting the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy, which currently calls for halving the use of pesticides by 2030 and reducing the use of chemical fertilisers by 20%, and was projected to lead to a 13% fall in agricultural production. “Europe cannot afford to produce less,” he said in March, arguing that “agricultural independence” must be a priority.

Triggering social unrest

If the state of agriculture in the EU is an example of poor long-term strategy, the response to supply disruptions this year shows the problems that can be done by short-term measures. We’ve seen multiple examples of countries banning or curbing the export of agriculture commodities and of the impact that has on prices. For example, in May Indonesia banned the export of palm oil to improve supplies of domestic cooking oil.

Palm oil is widely used in the food business, it’s a key and controversial ingredient in many processed foods and also in other products, such as toiletries. In response, the price of palm oil briefly soared, before falling back due to optimism that Malaysian production would help plug the shortfall and signs that Indonesia’s ban would be short-lived. We can expect to see a lot more incidents like this if food supplies remain disrupted, which will add to price volatility.

Why governments are quick to do this is understandable: food shortages are a major threat to public order. Take Sri Lanka’s ongoing crisis. Last year, the government banned the import of fertilisers in order to conserve foreign-currency reserves and told farmers to switch to organic farming. Yields plummeted, both in crops such as rice (a domestic staple) and tea (a key export and source of earnings).

Combined with other problems such as fuel shortages, the result was an economic crisis and widespread protests that forced out the president and prime minister. This is an example of what makes investing in food difficult: if prices get too high, the consequences can be social unrest rather than profits. Thus all investors should be alert to what the food crisis may mean for society, the economy and markets. Meanwhile, in the box below, I look at some of the firms best placed to manage food-price inflation and those that can benefit from helping boost production

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Frederic is an investment analyst. He started his career at JP Morgan in Paris. He has more than ten years of experience investing in private equity and also worked with the 3i debt management team investing in private debt. He is an ACCA member and a CFA charterholder. He graduated from Edhec Business School.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?Opinion The outlook for silver remains bullish despite recent huge price rises, says ByteTree’s Charlie Morris

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

-

The state of Iran’s collapsing economy – and why people are protesting

The state of Iran’s collapsing economy – and why people are protestingIran has long been mired in an economic crisis that is part of a wider systemic failure. Do the protests show a way out?

-

Why does Donald Trump want Venezuela's oil?

Why does Donald Trump want Venezuela's oil?The US has seized control of Venezuelan oil. Why and to what end?

-

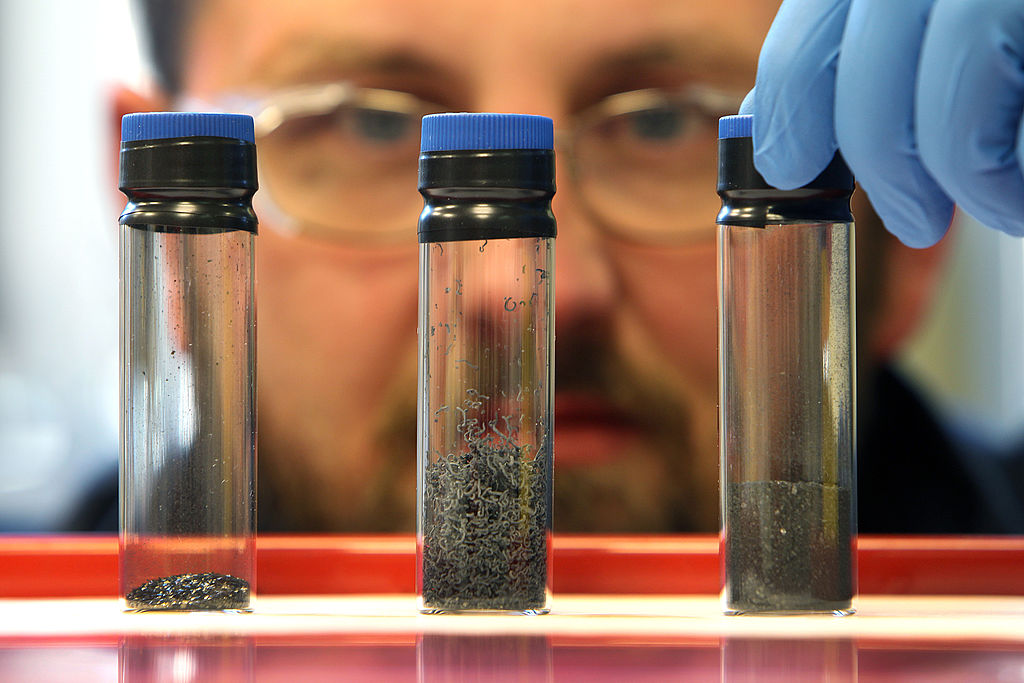

The graphene revolution is progressing slowly but surely – how to invest

The graphene revolution is progressing slowly but surely – how to investEnthusiasts thought the discovery that graphene, a form of carbon, could be extracted from graphite would change the world. They might've been early, not wrong.

-

Stock markets have a mountain to climb: opt for resilience, growth and value

Stock markets have a mountain to climb: opt for resilience, growth and valueOpinion Julian Wheeler, partner and US equity specialist, Shard Capital, highlights three US stocks where he would put his money

-

Metals and AI power emerging markets

Metals and AI power emerging marketsThis year’s big emerging market winners have tended to offer exposure to one of 2025’s two winning trends – AI-focused tech and the global metals rally

-

King Copper’s reign will continue – here's why

King Copper’s reign will continue – here's whyFor all the talk of copper shortage, the metal is actually in surplus globally this year and should be next year, too