What war in Ukraine means for agricultural commodities

With both Ukraine and Russia major producers of grain, vegetable oil and fertilisers, Saloni Sardana looks at how the conflict could affect supply.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent the price of many commodities, including energy and metals, soaring.

But we also risk seeing severe disruption to the global food supply if the war continues.

Ukraine’s soil, known as Chernozem, is incredibly fertile, so much so that the country is often described as the “breadbasket of Europe”. “It has the ability to provide food for half a billion people. Around 32 million hectares of land is cultivated every year and crops form the bulk of Ukraine’s national exports” as Spanish online newspaper AS reports.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So what does the invasion mean for food production?

What agricultural commodities are Russia and Ukraine known for?

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24th, the price of wheat rose to its highest level since the start of the year, and since then it’s continued to rise.

Ukraine and Russia are, respectively, the third and eighth-largest wheat producers in the world, says the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation. Together, they account for almost a third of the world’s wheat and barley exports.

Russia and Ukraine are also significant exporters of sunflower seed oil. In 2020, Ukraine produced 18% of the world’s sunflower seed, safflower, and cottonseed oil; 8% of its wheat and meslin (a mixture of wheat and rye); 12% of its barley; and 13% of the world’s corn, according to the International Trade Centre.

Russia is an even bigger food producer, with its sunflower seed, safflower or cottonseed production accounting for almost 40% of total global exports in 2020; and 18% of the world’s exports of wheat and meslin.

How will the war affect Ukrainian supplies?

So what happens given that so much of this supply is being cut off or disrupted? Clearly, we are looking at serious consequences for agriculture and food production, including “the disruption of business operations and trade flows, higher commodity and energy prices and a deteriorating economic outlook,” says Dutch bank ING. Already “the impact is trickling down to many food & agriculture companies in Europe and elsewhere”.

With men being called up to fight, harvests and transportation are already being drastically affected. Meanwhile, Oleg Ustenko, economic adviser to Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, points out that it may be impossible for Ukrainians to sow seed this year as “those parts of Ukraine which are most productive in terms of agricultural production are now consistently under aerial attack and artillery bombardment”.

Time is running out for Ukraine’s “spring sowing campaign”, the regular window for which runs in the first ten days of March. Planting needs to be fully completed in the last week of April.

“Working the fields in regions such as Chernihiv, Poltava, Kharkiv, Sumy, and Zhitomir has become practically impossible”, says Ustenko. There is “no way that Ukrainians will be able to sow this year based on a normal schedule”.

What effect will it have on Russia?

Although Russian agriculture has escaped sanctions (similarly to energy), “importers and exporters can still experience difficulties with settling payments in case their trade partners work with sanctioned Russian banks,” says ING.

Many international food companies have temporarily closed operations in or suspended exports to Russia. While local companies may choose to reopen if the security situation allows it, Western companies that have exited are unlikely to see any incentive to return quickly.

And even if seeds are grown and harvested, logistical issues due to the closure of Ukrainian ports and the security situation at the Black Sea mean exports could well be curtailed.

Which other countries are most vulnerable?

Russia’s invasion leaves many countries in Africa, Asia and the Middle East vulnerable to prolonged food shortages – Russia and Ukraine represent 70% of Egypt and Turkey’s wheat supply, for example. Ukraine is also a key exporter to Asia, while Russia meets most of Africa’s wheat demands.

A prolonged war means countries reliant on Ukrainian wheat could face shortages as early as July, Arnaud Petit, international grains council director, told The Associated Press.

"Up to 90% of Lebanon’s wheat and cooking oil imports come from Ukraine and Russia, as well as a large proportion of grain imports. The fighting in Ukraine has engulfed the country’s southern ports, putting a stop to shipments, and imports from Russia have been hampered as a result of financial sanctions imposed on Moscow”, says Al Jazeera.

African countries imported $4bn worth of agricultural products from Russia in 2020. Nigeria has already taken measures to lower its dependence on Russia for grains, but the disruption in food supplies has also reverberated further east, with the effects being felt in Asian countries such as Indonesia. Ukraine was the country’s second largest source of wheat in 2021.

In the Western world, the ongoing conflict will translate into higher costs for livestock feed, driving up the price of dairy and meat and driving up the price of US wheat exports.

How inflationary will this be?

How long the conflict will last could determine how far food prices will rise. But we should expect a significant jump, as food prices were rising around the world even before the invasion. Food prices in the UK rose by 2.7% in January for example, and the price of staple products such as peas, bread and eggs has risen by more than 10%.

The spectre of higher prices due to the conflict comes at a time when a drought in South America has already reduced soy supplies, and labour shortages in Malaysia are limiting the production of palm oil.

How does this affect fertiliser production?

The problems go beyond crops alone. The price of fertiliser, the key input in crop production, is also soaring in price.

Russia is the world’s largest producer of fertiliser, ahead of China, Canada, Morocco and the US. Russia is a major producer of ammonium nitrate and urea, and a big exporter of potash, an important nutrient for major commodity crops such as corn and soybeans. The fertiliser market was already being affected by soaring gas prices – natural gas is key to producing fertiliser from nitrogen.

“A prolonged disruption to the global supply of nitrogen and potash nutrients could cut into crop production in many parts of the world, for both the 2021/22 marketing year as well as 2022/23, at a time when food prices are already at record highs,” says consultancy Gro Intelligence.

Potash exports from Belarus have also been disrupted and the effects of Western sanctions may make this worse. Potash is a key ingredient in the production of major commodity crops such as soybean and corn.

Are there any investment opportunities?

Just as oil companies have benefited from the rise in oil prices, so fertiliser producers are profiting from global supply concerns.

German fertiliser company K+S (Frankfurt: SDF) may be worth investing in for the long term, says Brad Thomas in Seeking Alpha as “the company's strong focus on potash with its long-term superb strategy makes for an appealing investment, even if spot pricing for potash is historically volatile”. He thinks the stock price could rise by as much as 20% and expects a long-term price target of €26. Prices are currently trading at around €21.89.

Nasdaq recommends looking at Canadian fertiliser company Nutrien (NYSE: NTR). The company is also the world’s largest potash producer, with its six potash mines in Saskatchewan boasting more than 20 million tonnes of capacity. Nutrien is looking at selling 14.3 million tonnes of potash this year.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Saloni is a web writer for MoneyWeek focusing on personal finance and global financial markets. Her work has appeared in FTAdviser (part of the Financial Times), Business Insider and City A.M, among other publications. She holds a masters in international journalism from City, University of London.

Follow her on Twitter at @sardana_saloni

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Investors need to get ready for an age of uncertainty and upheaval

Investors need to get ready for an age of uncertainty and upheavalTectonic geopolitical and economic shifts are underway. Investors need to consider a range of tools when positioning portfolios to accommodate these changes

-

What happened to Thames Water?

What happened to Thames Water?Thames Water, the UK’s biggest water company could go under due to mismanagement and debt. We look into how the company got itself into this position, and what investors should expect.

-

How investors can profit from high food prices

How investors can profit from high food pricesA growing global population makes soft commodities a structural growth market. Amid rising food prices, here’s how to protect your profits

-

One day left for households to claim the £200 Alternative Fuels Payment to help with heating bills

One day left for households to claim the £200 Alternative Fuels Payment to help with heating billsAdvice Households could be due a £200 payment if they heat their homes using alternative fuel sources and aren’t connected to the mains gas grid - but time is running out to claim the money. We explain what you need to know.

-

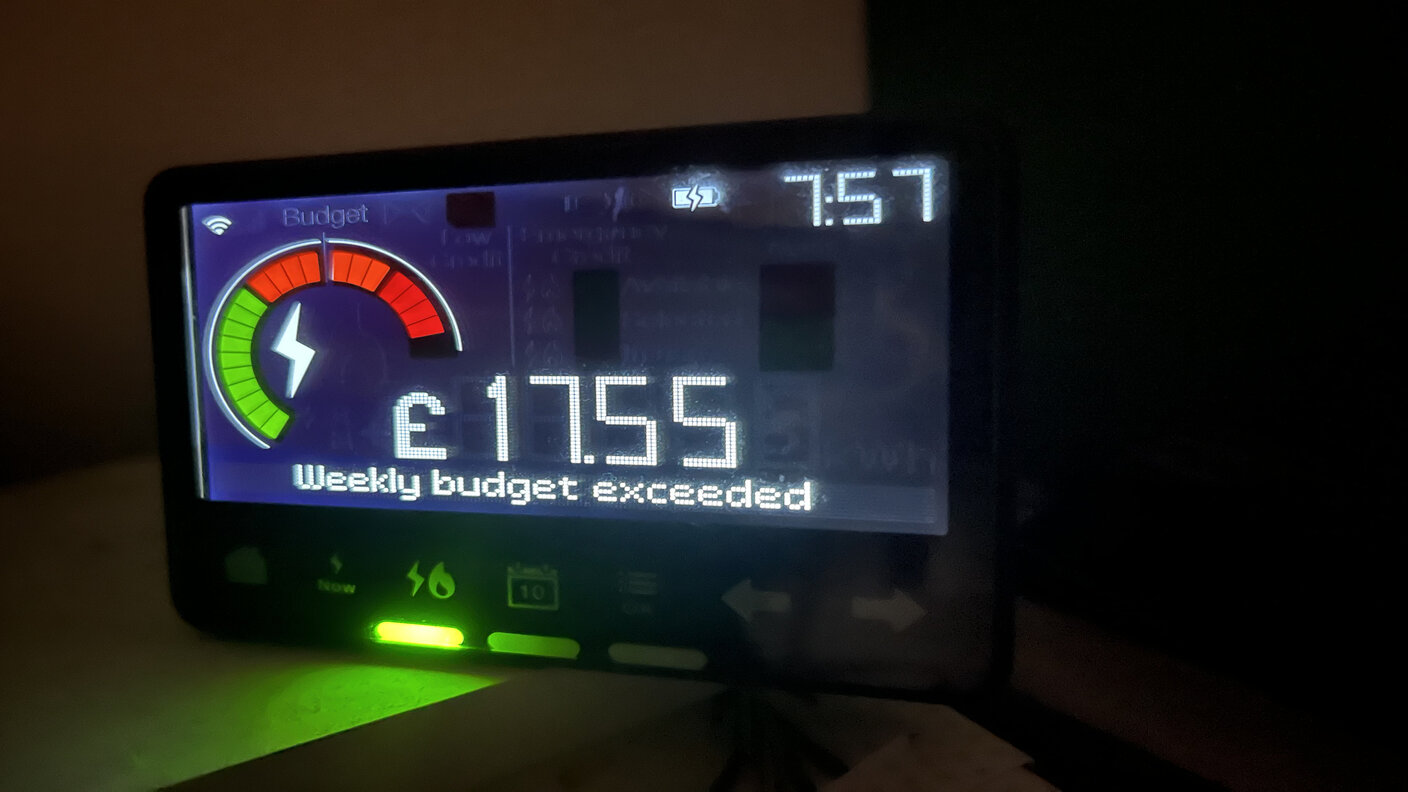

Energy bill to drop 17% this weekend as new price cap kicks in

Energy bill to drop 17% this weekend as new price cap kicks inNews Typical households on default energy tariffs will see their energy bills drop by £426 a year following today's energy price cap drop.

-

Don’t count resources out

Don’t count resources outAnalysis Commodities have performed poorly over the past year, but they tend to move in long and volatile cycles.

-

Energy bill refunds: Ovo and Good Energy to pay out £4m to customers who were overcharged

Energy bill refunds: Ovo and Good Energy to pay out £4m to customers who were overchargedNews Ofgem, the energy regulator, found the two suppliers had overcharged nearly 18,000 customers. Are you due a refund?

-

E.on Next, Good Energy and Octopus Energy pay £8m amid failures over late final bills

E.on Next, Good Energy and Octopus Energy pay £8m amid failures over late final billsNews Three energy firms have paid £8 million over compensation failures after lengthy delays in producing final bills to more than 100,000 customers when they switched suppliers