Why rare-earth metals are a good buy for investors

Raw materials are more plentiful than their name suggests. But demand is set to soar, implying long-term gains for investors, says David J. Stevenson

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Imagine that your smartphone doesn’t work. And if at the same time your laptop and television pack up, the electricity goes off and the car won’t start, you are facing a hugely inconvenient, if not downright alarming, scenario. In theory, this confluence of failures shouldn’t happen.

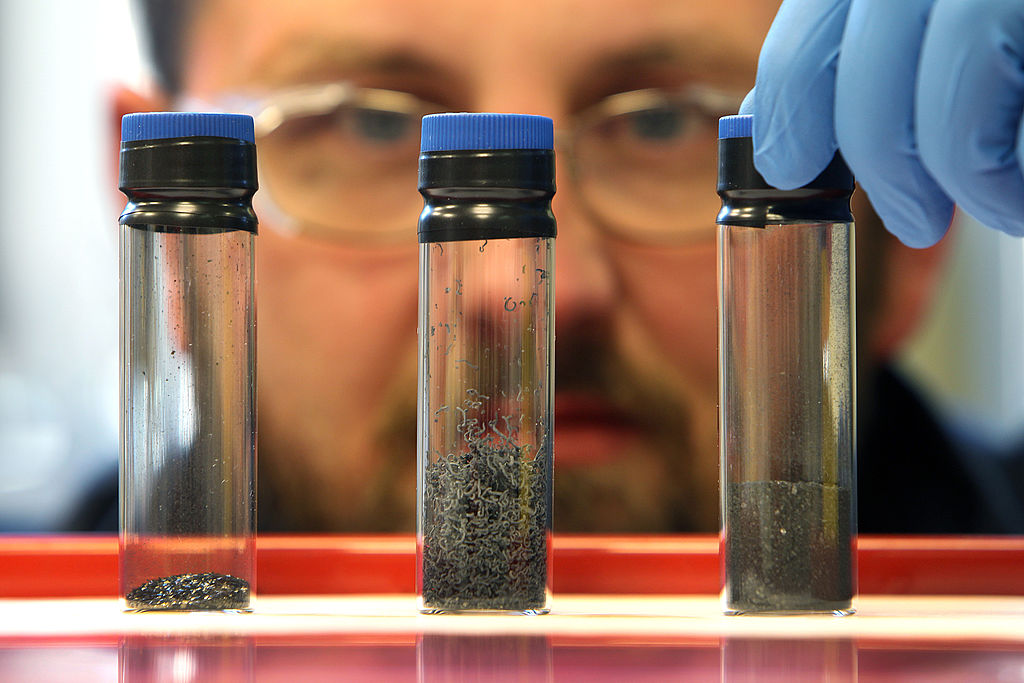

However, if one set of components within this equipment were absent, it would be inevitable. The vital ingredients? Rare-earth elements (REEs), comprising 17 metallic members of the periodic table. REEs may be just a small part of a product. Yet with their high melting and boiling points, they’re irreplaceable – either by themselves or in compounds – in many electronic, optical, magnetic and catalytic applications. Indeed, investors often call REEs “technology metals”.

The most important metals

Some of the most important ones include Yttrium, used in cancer and rheumatoid arthritis medications, surgical supplies, pulsed lasers and superconductors. Lanthanum – one of the most reactive REEs – accounts for up to 50% of digital camera lenses and mobilephone cameras. Other uses include wastewater treatment, petroleum refining, special alloys and steel purification. Gadolinium provides shielding in nuclear reactors and in neutron radiography.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

It is also used for targeting tumours, enhancing magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and in X-rays and bone-density tests. Terbium (so soft, it can be cut with a knife) is used in compact fluorescent lighting, colour displays, fuel cells, electronic devices and naval sonar systems. In alloy form, Terbium has the highest “magnetostriction” of any substance (it can change its shape). This makes Terbium a key component of Terfenol-D, which is employed in many defence and commercial technologies. Erbium is widely found in nuclear applications, such as neutron-absorbing control rods. It is also a vital part of high-performance fibre-optic communications systems and lasers.

Structural growth in demand

While substitutes are available for many applications, they tend to be less effective. Meanwhile, the REE recycling rate is below 5%. Yet future demand for REEs is set to be unrelenting. Last year the market generated $7.1bn in revenues, according to market-research group P&S Intelligence. It forecast 9% compound annual growth until 2030. Fortune Business Insights, another researcher, expects 10% annual growth for REEs between 2021 and 2028, with major catalysts being increasing demand for tablets, laptops, smartphones and electric vehicles (EVs). Researcher Adamas Intelligence expects that the world’s need for the most widely used type of rare-earth magnets – NdFeB, also known as neodymium magnets – to increase at an annual growth rate of 8.6% from 2022 to 2035.

Common applications include hard-disk drives, on-off buttons, and magnetic separators. The magnets are also important in MRI scanners, precision-guided weapons and defence-related stealth technology. Owing to double-digit demand growth from EVs and wind power, requirements for magnetic REEs such as neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium are likely to increase at the same rate, says Adamas. With global production of these metals likely to grow at just 5.4% annually, this means higher prices.

Extraction is costly What about supply?

Paradoxically, not all REEs are as rare as their name suggests. Some are relatively plentiful, in fact. Thanks to their geochemical properties, however, REEs tend not to be located in This remains a concern for the West. It’s no surprise, then, that the US Department of Energy wants feedback from industry, academia and research laboratories (among others) on developing a critical-materials supply chain, including for REEs used in wind turbines and solar panels.

The private sector is also pursuing REEs. “Some of the world’s richest men are funding a massive treasure hunt… [in] Greenland,” says René Marsh at CNN. “Billionaires, including Jeff Bezos, Michael Bloomberg and Bill Gates …[are] betting that below the surface of the hills and valleys on Greenland’s Disko Island and Nuussuaq Peninsula there are enough critical minerals to power hundreds of millions of electric vehicles.” “The billionaire club is financially backing KoBold Metals, a mineral exploration company and Californiabased start-up,” reports CNN. “KoBold is partnered with Bluejay Mining to find the rare and precious metals in Greenland [needed] to build electric vehicles and massive batteries to store renewable energy.” The upshot is that some REE miners will profit handsomely from selling their wares.

There are, of course, risks, as with all mining ventures. Not all will prove successful. REE prices can be volatile. In particular, a sudden supply surge caused by a major discovery – or a stronger dollar, in which most REEs are priced – could depress metal values in the short to medium term. So investors may prefer to stick to the larger, more diversified REE players, though for those who like a bit more spice, smaller operations could provide more upside (or downside, if plans don’t work out). We offer three ideas in the column to the right. sufficiently concentrated deposits for viable mining, while they are difficult and costly to extract and process.

In 1993, 38% of global REE output emerged from China, 33% came from the US, and 12% from Australia, while Malaysia and India contributed 5% each. But 15 years later, China comprised more than 90% of global REE production. China still rules the roost. But last year was better balanced: about 60% of REE-mine production still came from China, while the US, Burma and Australia provided 15%, 9% and 8% respectively. Despite the gradual easing of that previous stranglehold, China still has a strong strategic advantage.

What to buy now?

Lynas Rare Earths (Sydney: LYC) boasts the Mt Weld Central Lanthanide Deposit (CLD), one of the highestgrade rare-earth deposits in the world. Mt Weld also encompasses other resources, such as the undeveloped Duncan, Crown and Swan deposits, which contain rare-earth metals, titanium and phosphates. Lynas processes ore at its Mt Weld plant, producing rare-earth concentrate that is sent for further processing at the Lynas Advanced Material Plant near Kuantan, Malaysia.

One of the world’s largest and most modern rare-earth separation plants, Lynas Malaysia, treats the Mt Weld concentrate and makes rare-earth oxide (REO) products to sell worldwide. The firm is opening a processing facility at Kalgoorlie in Australia and recently won a $120m contract from the US Department of Defence to build a heavy rare earths facility in America. Lynas has an A$8bn (£5.3bn) market capitalisation.

Record sales receipts of A$351m were achieved for the quarter to 30 June 2022 and there is A$966m of cash on hand to fund continued growth as demand for REEs rises. On forward price/earnings (p/e) ratios from the current year to 2024 of 10.3, 9.6 and 8.4 respectively, according to estimates compiled by MarketWatch, Lynas is a cheap longterm growth stock.

The largest REE stock is MP Materials (NYSE: MP), which owns and operates Mountain Pass, one of the world’s richest REE deposits and the only integrated rare-earth mining and processing site in the Western Hemisphere. It has huge geological advantages, averaging a 7% rare-earth content compared with the 0.1%-4% density seen in most global REE deposits. It is also self-contained (with co-located mining, milling, separations and finishing areas), which saves money and reduces operational risks. MP delivers 15% of global rare-earth supply with a long-term focus on Neodymium-Praseodymium (NdPR), an oxide based on the two metals that power the strongest kinds of rare-earth magnets.

Furthermore, the firm’s results are improving fast. For the three months to 30 June 2022, MP reported a 96% year-on-year revenue surge driven almost entirely by rising REO concentrate prices (production was broadly unchanged). Net income soared by 170% year-on-year, while earnings per share rose by 153%.

The market cap is $6.6bn. As at the end of 2021, MP had almost $1.2bn of cash and $700m of long-term debt. So there is ample scope for the group to develop its operations. On a 2024 p/e of 20, it is reasonably priced given its potential. It is a long-term buy. A much more speculative REE play is Bluejay Mining (Aim: JAY), mentioned above. It describes itself as a Greenland-centric, multi-commodity, multi-project exploration and development resource business.

The company says its near-term focus is its Greenland-based Dundas Ilmenite Project, the world’s most significant sand ilmenite (a titanium-iron oxide mineral) deposit. Bluejay is also looking to develop its other projects that provide exposure to nickel, copper, lead, zinc and platinum. Greenland could have plentiful resources of coal, copper, gold, rare-earth elements and zinc, according to the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland. The tie-up with KoBold Minerals looks promising. The latter isn’t currently receiving any revenue, though, so depends on shareholders stumping up enough money to finance expenses until it can generate cash flow. The risk here is that if new equity is issued at a discount to the prevailing stock price, this will dilute the interests of existing shareholders.

Bluejay’s market cap is £68m. For the year ended 31 December 2021, the pre-tax loss was £2.7m. At that date, the company held cash and cash equivalents of £2.7m (with no debt). In March this year, Bluejay bolstered its liquidity position with a £5.4m share placing. The upshot? Bluejay remains high-risk, but it could be a high-reward long-run investment.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

David J. Stevenson has a long history of investment analysis, becoming a UK fund manager for Oppenheimer UK back in 1983.

Switching his focus across the English Channel in 1986, he managed European funds over many years for Hill Samuel, Cigna UK and Lloyds Bank subsidiary IAI International.

Sandwiched within those roles was a three-year spell as Head of Research at stockbroker BNP Securities.

David became Associate Editor of MoneyWeek in 2008. In 2012, he took over the reins at The Fleet Street Letter, the UK’s longest-running investment bulletin. And in 2015 he became Investment Director of the Strategic Intelligence UK newsletter.

Eschewing retirement prospects, he once again contributes regularly to MoneyWeek.

Having lived through several stock market booms and busts, David is always alert for financial markets’ capacity to spring ‘surprises’.

Investment style-wise, he prefers value stocks to growth companies and is a confirmed contrarian thinker.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?

Silver has seen a record streak – will it continue?Opinion The outlook for silver remains bullish despite recent huge price rises, says ByteTree’s Charlie Morris

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

-

The state of Iran’s collapsing economy – and why people are protesting

The state of Iran’s collapsing economy – and why people are protestingIran has long been mired in an economic crisis that is part of a wider systemic failure. Do the protests show a way out?

-

Why does Donald Trump want Venezuela's oil?

Why does Donald Trump want Venezuela's oil?The US has seized control of Venezuelan oil. Why and to what end?

-

The graphene revolution is progressing slowly but surely – how to invest

The graphene revolution is progressing slowly but surely – how to investEnthusiasts thought the discovery that graphene, a form of carbon, could be extracted from graphite would change the world. They might've been early, not wrong.

-

Stock markets have a mountain to climb: opt for resilience, growth and value

Stock markets have a mountain to climb: opt for resilience, growth and valueOpinion Julian Wheeler, partner and US equity specialist, Shard Capital, highlights three US stocks where he would put his money

-

Metals and AI power emerging markets

Metals and AI power emerging marketsThis year’s big emerging market winners have tended to offer exposure to one of 2025’s two winning trends – AI-focused tech and the global metals rally

-

King Copper’s reign will continue – here's why

King Copper’s reign will continue – here's whyFor all the talk of copper shortage, the metal is actually in surplus globally this year and should be next year, too