Can China hold the world to ransom over access to rare-earth metals?

China’s stranglehold on rare-earth minerals – resources essential for our modern high-tech world – has some analysts worried. Should we be too?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What’s happened?

Fears are growing that China’s current high-level review of its rare-earths policy could presage export restrictions that will wreck the supply chains for strategically crucial sectors including electric vehicles and renewable energy. China currently produces about 70% of rare-earth elements globally, and has used its dominance in the past as geopolitical and economic leverage. Citing anonymous sources close to China’s review, Bloomberg reports that Beijing could ban the export of rare-earths refining technology to countries or companies it deems as a threat. And although China has no imminent plans to restrict shipments to the US, it is keeping that option in its “back pocket” if Sino-US relations deteriorate further, the source said. A source quoted by the Financial Times similarly said that China is considering restrictions on the export of rare-earth minerals that are crucial to the manufacture of US F-35 fighter jets and other weaponry.

What exactly are rare earths?

They are the 15 metallic lanthanide elements on the periodic table, plus two other closely related elements, scandium and yttrium – and they are an integral part of modern life, crucial to several high-tech sectors. Despite the name, almost all of the 17 rare-earth elements are actually pretty plentiful in the earth’s crust. Sixteen of the elements are more abundant than gold. And one of them, cerium, is the 25th most abundant element on the planet. However, they tend to be widely dispersed, and their geochemical properties make them hard, environmentally damaging and expensive to mine and process, producing large quantities of toxic wastewater and radioactive residues. For that reason, there are very few places in the world where it has proved practical and profitable to mine them. Hence the name “rare”.

What are their uses?

They’re used in high-tech equipment in crucial sectors including electric vehicles and wind energy, consumer electronics, defence and oil refining. For example, powerfully magnetic rare earths such as neodymium, terbium and dysprosium are used as magnets in electric-vehicle motors. Hybrid car batteries also use the rare earth lanthanum. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners in hospitals use the rare earth gadolinium. Apple iPhones contain rare earth elements and they are crucial components in solar cells and lasers. Britain has high hopes of becoming a renewables superpower in the coming decades. But each of its vast Dogger Bank wind turbines will rely on tonnes of rare-earth elements.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Why is China so dominant?

In part, geology: China has an estimated 40% of global reserves, concentrated in the sparsely populated northern province of Inner Mongolia. But crucially, in recent decades China has also had a far greater tolerance for the environmental damage inflicted by their extraction. It overtook the US as the world’s biggest producer of rare earths in the 1990, and has never looked back. It has also converted its control of the raw materials into dominance of the valuable next steps: turning oxides into metals and metals into products. In 1992 Deng Xiaoping quipped that “the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths”. But as The Economist points out, China’s position three decades on is “as if the Middle East not only sat on most of the world’s oil but also, almost exclusively, refined it and then made products out of it”.

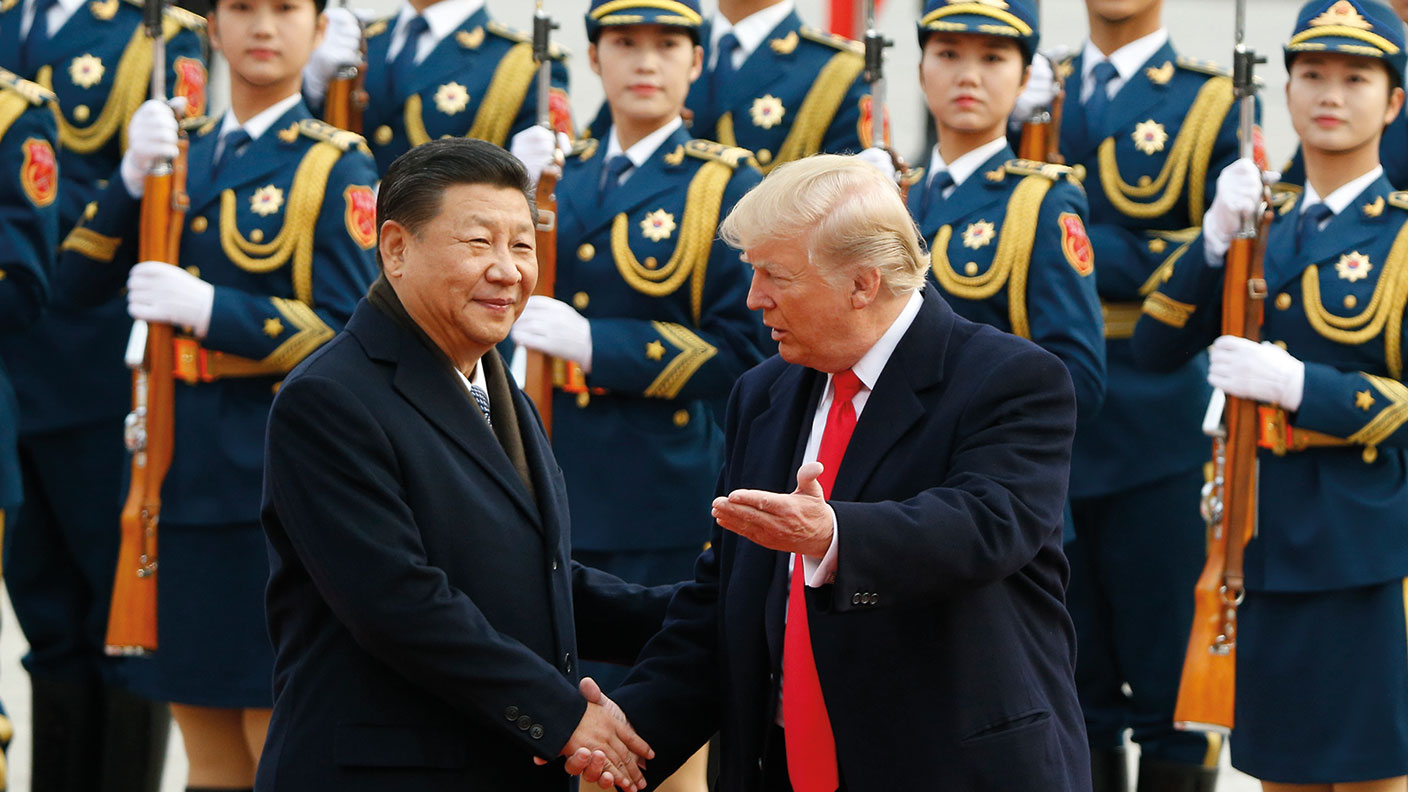

And China has exploited this dominance?

In 2019, at the height of Donald Trump’s trade war with China, Beijing threatened to cut off supply of rare earths. And in 2010 it did create a genuine global supply crisis – and massive price rises – when it cut export quotas to punish Japan over a territorial dispute in the South China Sea, and help domestic manufacturers. However, their “cunning plan was eventually foiled by a combination of market forces and global trade rules”, says Alan Beattie in the FT. Higher global prices made it profitable to open mothballed mines in Australia, California and elsewhere. Smuggling undermined the export controls. And a WTO case brought by the US ruled against China, which largely complied with the decision. Since 2010, China’s proportion of rare-earths production has fallen from 95% to around 75%. However, a big slice of the difference is accounted for by just one player – the Japanese-backed Australian firm Lynas, which owns the Mount Weld mine in Western Australia and a vast processing plant in Malaysia.

But there’s no real need to worry?

Some commentators think the West has learned the right lessons from the 2010 scare. When Arab countries used their dominance of oil exports to push up the price of crude in the 1970s, says David Fickling on Bloomberg Opinion, the “outcome was not a permanent Gulf stranglehold on energy but a rush to diversify”. The same is happening with rare earths. They are important, yes, but political restrictions on exports will only cause major importers to reconfigure their supply chains to be more resilient – and would ultimately prove self-defeating for a Chinese economy that is far more globally integrated than it once was.

What’s the counter-view?

The strategic and security implications mean that the West cannot afford to be sanguine, however, say James Conway and Peter Ackerman in the FT. While “oil is a global industry, minerals processing and electric vehicle component manufacturing is almost exclusively Chinese”. If left unchecked, this dominance will become a “strategic vulnerability” for the US and Europe, especially if they are to hit climate policy goals. “We risk a scenario in which we swap our dependence on a chaotic oil market dominated by Opec countries that do not share our strategic goals, for a reliance on China for our future transportation needs.” A critical mineral supply chain that is less dependent on China is a matter of national security.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton