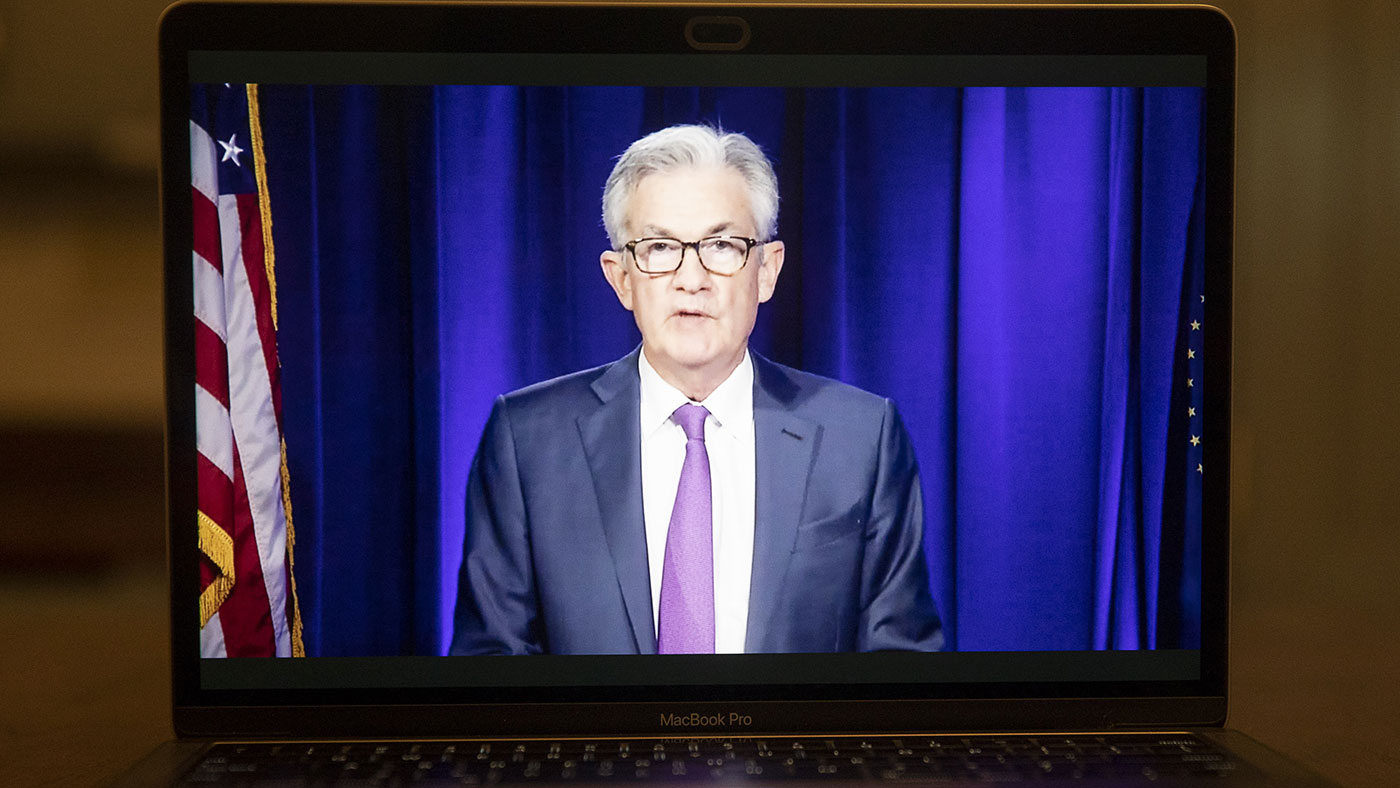

Central banks want politicians to take charge – but what will they do?

The US Federal Reserve has come to the end of the road in terms of what it can do to accelerate any recovery, says John Stepek. It's over to the politicians to act.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve’s committee for setting monetary policy finished up the first meeting of a new era.

The Fed said that it’s now planning to keep interest rates at zero until inflation “is on track to moderately exceed 2% for some time”.

That’s really quite a big deal. Especially as the Fed currently doesn’t think that will happen until at least the end of 2023, which means rates won’t be rising for at least another three years.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So why did markets give a big shrug?

Interest rates aren’t going anywhere for a very long time

The Federal Reserve has been shifting the goal posts on its monetary policy aims for a while now. But now it’s very much official.

The Fed now wants inflation to be above its original 2% target for a while (it’s not specified how long) to compensate for inflation being below 2% for a while. It’s also placing a higher priority on employment than it previously did (again, this is hard to measure, it’s more about emphasis).

In short, the Fed is acknowledging that what economists once assumed about the link between employment and inflation (if employment goes too high, you'll get inflation) isn’t working any more.

So this implies a few things. It implies that monetary policy will be loose – sitting at what we would once have described as “emergency levels”, but is really now just normality – for a very long time indeed.

It also implies that the Fed should be more aggressive in terms of things like quantitative easing and the like. Not just using it for emergency purposes, but also if it feels that inflation simply isn’t rising fast enough.

All of this sounds quite radical, and at one point, it would have been. The kind of thing that not only saw gold, for example, at record highs, but surging a lot higher.

But markets are all about expectations. And by now, when it comes to the Fed, as far as the market is concerned, anything less than walking on water is a bit of an anti-climax.

The thing is, for all its talk, the Fed didn’t actually do anything extra. And that leaves markets in a bit of a limbo situation.

The rebound since the March lows has been driven by two things. One factor is that once an economy has tumbled off a cliff, things can only get better. Once the news stops getting worse, markets tend to turn around. That’s your “relief rally”, where markets go up because although the news is bad, it’s less bad than expected.

But that only lasts for so long. Eventually, markets get ahead of themselves again, and you start getting disappointed reactions even when the economic data is much better than expected.

The Fed wants politicians to act – but will they?

The second factor – and arguably the more important one – is, of course, the Fed. The US central bank reacted very quickly during this crisis to underwrite not only the US financial system, but also the global financial system.

That prevented us from getting that existential panic we saw in 2008, where no one would willingly put a price on anything, because no one was entirely sure that anyone would still be in business the next day.

But having underwritten the system, it’s not clear what the Fed can now do by itself to accelerate any recovery. This tells us something about where we are in terms of the politics of monetary policy.

I listened to an excellent Bloomberg “Odd Lots” podcast the other day with Paul McCulley, formerly chief economist at bond fund giant Pimco. He argues that, in effect, we’re now seeing a shift from a technocratic “monetary policy dominant world” back to a democracy.

In other words, control of money is moving from capital (the relative minority of people who own assets and already have money) to labour (the majority of people who earn their money from wage income rather than assets).

You can certainly take issue with McCulley’s framing of the topic. But the picture he sketches – where monetary policy is basically at the end of the road, and politicians now are taking charge, one way or the other – I feel, is accurate.

So really what the Fed is now doing is similar to what the European Central Bank spent a lot of time saying a few years ago under Mario Draghi.

That is: “Politicians, it’s up to you. We’ll keep interest rates low. We’ve got your back. You now need to spend money to get the economy going and employment rising.”

Eventually, you have to expect that someone will take the central banks of the world up on that offer in a wholehearted manner, as opposed to the somewhat more timid approach we currently have.

So that’s the overall narrative. It’s not so much that central banks are out of ammo. But they’re at the stage where they really need to hand the gun over to the elected politicians. It’s one thing to simply print money. It’s quite another to decide who gets it. Voters need a say in that.

The question now is: when does the shift actually happen?

The obvious move would come if US politicians can agree to a deal to extend coronavirus stimulus packages further. I suspect any deal would send markets a lot higher. However, given that we’re getting ever closer to what promises to be a very bad-tempered election, there’s clearly a good chance that this won’t happen.

I would expect the next president – whoever gets in – to try to splurge a bit. But you have a long period of no man’s land between now and then. And that period might well be extended by any disputes over the result.

So it’s an interesting environment for financial markets, particularly given that most assets seem to be priced quite highly. Will we get a correction before or during the election? Or will everything keep heading higher?

Something to watch is that right now, stock markets are teetering on various important technical indicators (Dominic has written about them a few times recently). Whatever you think of charting, these are lines and levels that lots of people in markets do pay a lot of attention to.

If markets slide below them, that might be enough for a lot of people to take profits and sit on their money until the election uncertainty has passed, or until the Fed comes out with some other sort of massive bribe to force people back into the market.

Again, this is mostly for interest. Unless you’re a short-term trader (I don’t recommend it), then none of this should affect your long-term plan. But it’s nice to know what might lie ahead, so that you a) don’t panic; and b) make sure you’re prepared to take advantage of any opportunities that arise if everyone around you starts to panic.

And if you haven’t already, then do subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine. You can get your first six issues free here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'

'Investors should brace for Trump’s great inflation'Opinion Donald Trump's actions against Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell will likely stoke rising prices. Investors should prepare for the worst, says Matthew Lynn

-

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'

'Governments are launching an assault on the independence of central banks'Opinion Say goodbye to the era of central bank orthodoxy and hello to the new era of central bank dependency, says Jeremy McKeown

-

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?

Will Donald Trump sack Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chief?It seems clear that Trump would like to sack Jerome Powell if he could only find a constitutional cause. Why, and what would it mean for financial markets?

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?

Can Donald Trump fire Jay Powell – and what do his threats mean for investors?Donald Trump has been vocal in his criticism of Jerome "Jay" Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve. What do his threats to fire him mean for markets and investors?

-

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?

Do we need central banks, or is it time to privatise money?Analysis Free banking is one alternative to central banks, but would switching to a radical new system be worth the risk?