Britain has a new chancellor – get ready for a major spending splurge

The departure of Sajid Javid as chancellor and the appointment of Rishi Sunak marks a change in the style of our politics. John Stepek explains what's going on, and what it means for UK assets and for your money.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Poor old Sajid Javid. Last year, the then-chancellor was warming up to give his first budget speech. But a pesky general election got in the way. Never mind. The Conservatives won, and so it looked as if he’d be having his big moment on 11 March.

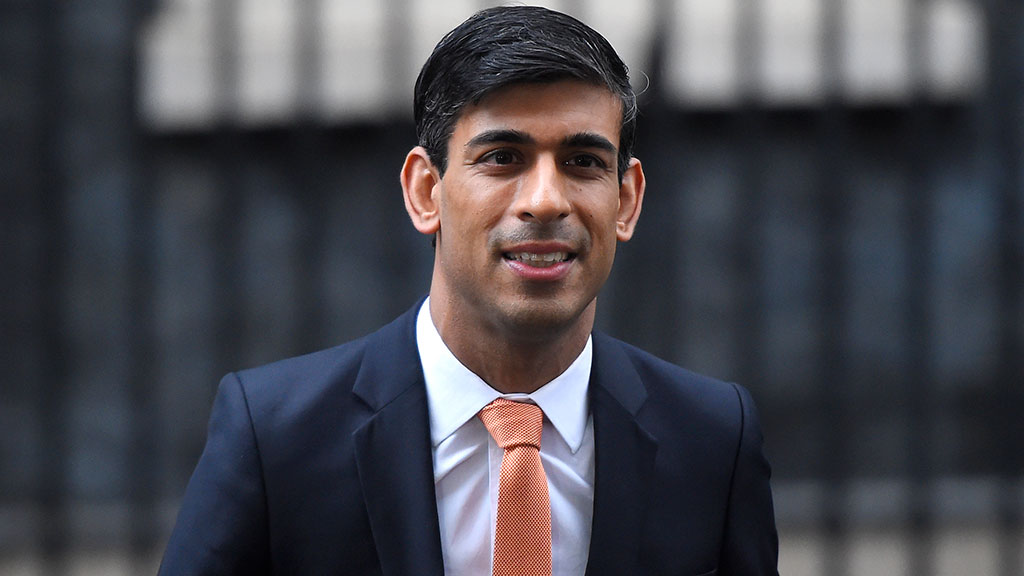

But yesterday, Javid resigned. We now have a new chancellor – Rishi Sunak, who was Javid’s deputy – and we’ll never get to hear what might have been in Javid’s Budget. So what’s going on?

Politics is no longer about power-sharing

I’m not a political journalist. I write about money. So I’m not party to all the gossip and I can’t say I’m especially interested in most of it. So my take on Sajid Javid’s resignation isn’t based on anything more than observation.

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

That said, it's pretty obvious what happened. Politics is about power. The Treasury has always been its own wee fiefdom within Westminster, and I think – although I’d again emphasise my lack of specialist knowledge on this front – it’s fair to say that this splintering got worse during the Gordon Brown years.

In effect, you had the chancellor running the economy, and the prime minister wafting around dealing with foreign policy, world-stage stuff, and hoping for a nice sinecure in Europe at some point during retirement.

In the era of globalisation, the domestic economy was boring. Central banks had a handle on the important bits. The rest was about plucking the goose and redistributing the spoils in such a way as to maintain a client base of voters.

Prime ministers like David Cameron and Tony Blair were happy to hand that technocratic stuff over to their smart but uncharismatic sidekicks. They did the glamour and the glad-handing – Brown and Osborne got their semi-annual ego trips every budget day – and they all felt broadly happy.

Those days are gone.

Globalisation and supra-nationalist technocracy – the vision of a world run by a Platonic guardian class who mostly studied PPE and/or worked at Goldman Sachs (ironically, of course, the new chancellor ticks both those boxes) – is giving way to local politics and a craving for accountability again.

You can call that populist or you can call it a necessary correction in the balance of power, depending on your position. But that’s what’s happening.

A key example here is central banks. Central banks are not out of ammo (money printing represents an endless supply of bullets), but they lack the authority to go much further than they already have. This conflict is most apparent within the eurozone but that’s only because there are different countries involved – it’s the same problem everywhere, just less visible.

In any case, in a de-globalising world where central bankers have lost their status, the domestic realm becomes exciting once again, while the international stuff is reduced to a series of dull meetings in conference rooms in hotels near different airports. And that means you can ditch this informal power-sharing nonsense. There’s only room for one boss – and that’s going to be the prime minister.

So as I understand it, Sajid Javid and Boris Johnson were on the same page on a lot of things. But Johnson wanted a clear-out of the Treasury.

The idea of having his plans thwarted by a group of technocrats who have decided that there’s only one specific way to grow an economy sustainably is not something Johnson (or his adviser, Dominic Cummings, presumably) is happy with.

Javid meanwhile recognises a power grab when he sees one. Do you swallow your pride, when you’re clearly being undermined (even if it’s put nicely)? Or do you think – “I don’t need this. I don’t need the money, I’m not getting the status, so this is an embarrassment too far” – and step down? His decision to resign is entirely understandable and I think most of us would’ve done the same.

The new chancellor is good news for UK assets

So that’s the gossip and speculation side of things. Such fun. But what does it mean for your investments?

In terms of minor practicalities, I suppose the Budget might be delayed. Sunak doesn’t have a lot of time to catch up. Then again, I suspect that Johnson and Cummings know exactly what they want, so sticking with the current date could be the best way to ride over any potential opposition.

In terms of the important stuff – I mean, I think it’s obvious. The point of the first post-Brexit Budget is that it was meant to be a big firework of spending.

It’s all about Britain breaking free, about recognising its potential. It’s about obliterating any vestiges of austerity (still the most consistent attack line from the various parties of opposition, and thus the one that any strategist should focus on undermining), about a statement of self-confidence, and about “getting things done”.

It’s not about fretting over balanced budgets, taking from Peter to pay for Paul (or slashing entrepreneur’s relief to pay for railways in the north of England), and general timidity or caution.

As RBS economists Cathal Kennedy and Peter Schaffrik told Bloomberg: “Why go through the trouble of reorganising the workings of the Treasury and essentially push an unacceptable arrangement on the chancellor, if there are no big changes planned?”

Whether you are on board with Brexit or you think it’s daft, this was the whole sales pitch of the Johnson government. The next budget is bonanza time. It’s a “feelgood” budget.

That means more government spending, definitely. That means a bigger deficit, definitely. That means making up some flimflam rules about balancing the books (excluding spending for investment, and as we know, all government spending is “investment”) in a century’s time.

And you know what? It won’t matter. Because every country is running a deficit and right now markets have given up on inflation ever returning in any serious form to any nation in the world.

They’re wrong. But the belief can certainly hold true for long enough for Johnson to get a sugar high at minimum – and potentially, a genuine morale boost and maybe even business investment and productivity gains – without completely demolishing sterling or the gilts market.

In fact, looking at the reaction of the markets yesterday – they were pretty positive about the idea of ambitious spending. Gilt yields rose (so gilt prices fell). But the pound rose too. To my mind, that suggests a market pricing in a stronger economy. (A more expansionary Budget means a stronger economy, means less need for Bank of England interest rate cuts, which means higher interest rates, which means a stronger pound).

What’s the upshot? In the short-to-mid-term at least, this is probably good news for the UK economy and for UK assets. But let’s see what the new chancellor actually comes out with at the budget. (Assuming he’s still in the job by then).

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.