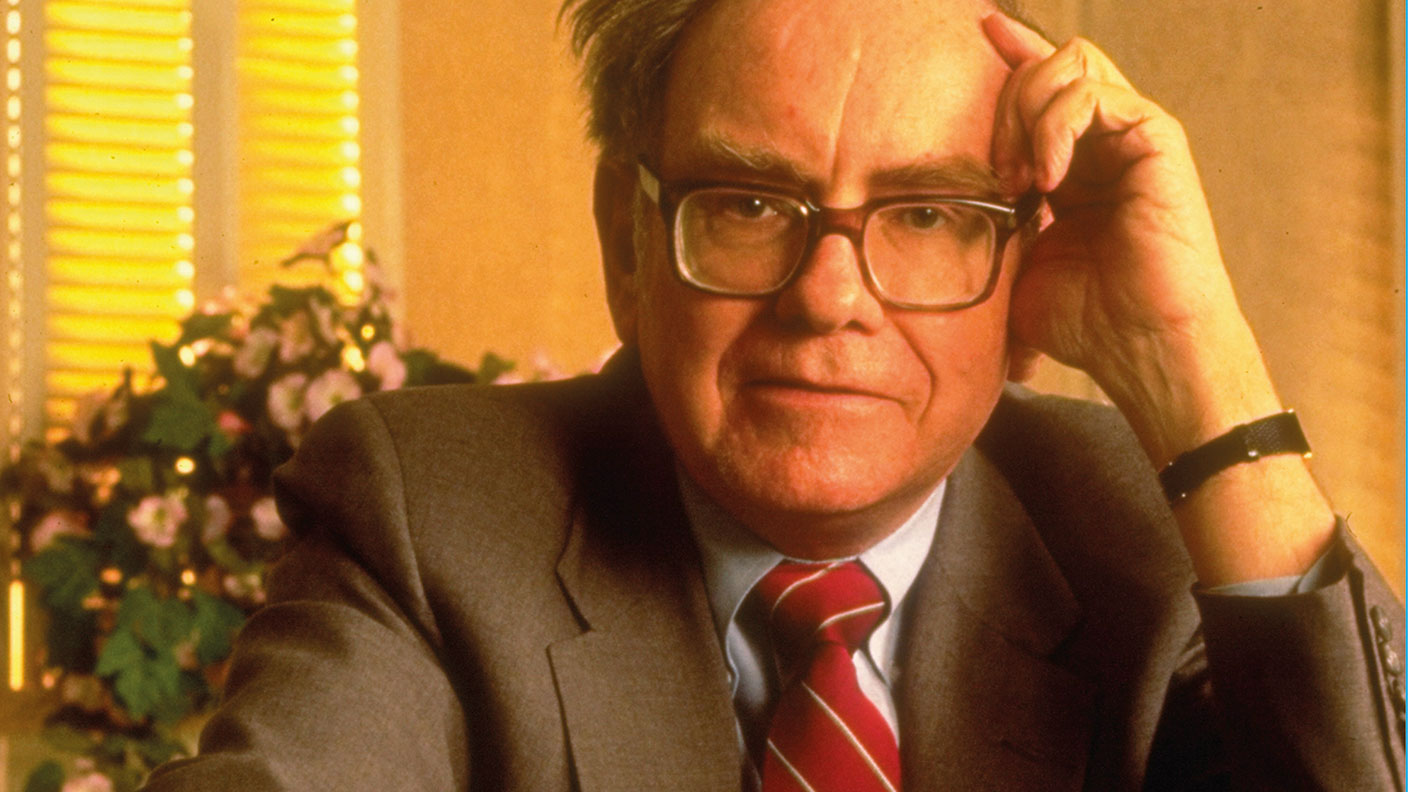

The making of Warren Buffett

The man who “triumphed in the long game by practising a simpler, purer version of capitalism” is widely hailed as the world’s greatest living investor. How did he get to where he is today?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

On the walls of Berkshire Hathaway’s offices, framed front pages from days of market panic, such as the 1929 crash, “serve as a reminder not to succumb to the passions of the moment”, says The New Yorker. Warren Buffett’s “ability to divorce himself from emotion” has always been part of his genius as an investor. And he hasn’t lost his head now. But he does seem to have lost his edge and is the first to admit it.

Asked last year which would be the better investment to put in a child’s account – a share in Berkshire Hathaway or a share in an S&P 500 tracker fund – Buffett didn’t hesitate, “I think the financial result would be very close to the same”. The statement, notes the FT, was made “without qualification”. Still, it’s hard not to wonder if Buffett, even at 89, is underplaying his ambitions. After all, he’s a PR genius too – “cultivating an aw-shucks, Midwest-wholesome image of a man who has triumphed in the long game by practising a simpler, purer version of capitalism”.

A schoolboy out-earns his teachers

Buffett’s “plain-dealer persona” is integral to the Berkshire enterprise: “I buy expensive suits – they just look cheap on me”, is one of his famous quips. The business continues to occupy “a single floor in an unexceptional office tower in Omaha that bears another company’s name”. Buffett himself lives in “the same house he bought in the 1950s” and still works at the desk used by his father, a stockbroker turned Republican congressman. “Both Buffett and Berkshire are superficially unchanged.” Yet their investment formula has shifted considerably down the years. The man who warned in 2003 that derivatives were “weapons of mass destruction” made good use of them himself after the crisis. Indeed, until this latest blip, “the degree to which Buffett has outwitted successive generations of Wall Street rivals almost defies comprehension”.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Buffett’s financial career began officially at the age of 14 when he filed his first tax return having saved $1,000 from early ventures including a paper round, says The Observer. He had bought his first shares aged 11. Born in 1930, his early years were shaped by the Great Depression and “his corrosive relationship with his mother”, who all the children were terrified of. An unusual boy, “obsessed with numerical calculation and arcane research”, Buffett would “compare the lifespans of those who composed hymns” at church on Sundays, says The New York Times. By the time he finished high school his ventures had come to include pinball machines and he was earning “more money than his teachers”.

The great investor learns how to live

A key turning point came when, on rejection by Harvard Business School, he went to Columbia instead. A professor there, Benjamin Graham, the so-called “father” of value investing, became Buffett’s mentor and role model, says The New Yorker. From Graham, Buffett – who put in a short stint on Wall Street before returning to Nebraska to marry and set up shop on his own – learned the idea of buying “cigar butts”: companies on their last legs, but so undervalued they’re worth “one last puff”. But it was his partnership with Charlie Munger – the pair first met in 1959 – that was “instrumental in moving Buffett from buying bad businesses at cheap prices to buying great businesses – most famously, Coca-Cola – for reasonable prices”, a move that was the foundation of his great fortune.

Buffett’s children later described him during those years as “the disengaged, silent presence, feet up in his stringy bathrobe, eyes fixed on The Wall Street Journal at the breakfast table”. Cerebral and inward-looking, he “attributes much of his later success to taking a Dale Carnegie public-speaking course as a young man”, says The New Yorker, and much of his “evolution as a person” to his late wife, Susan, who pushed him to give more of his money away during his lifetime. “Buffett was born to be great at investing. He had to work really hard to be good at living.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

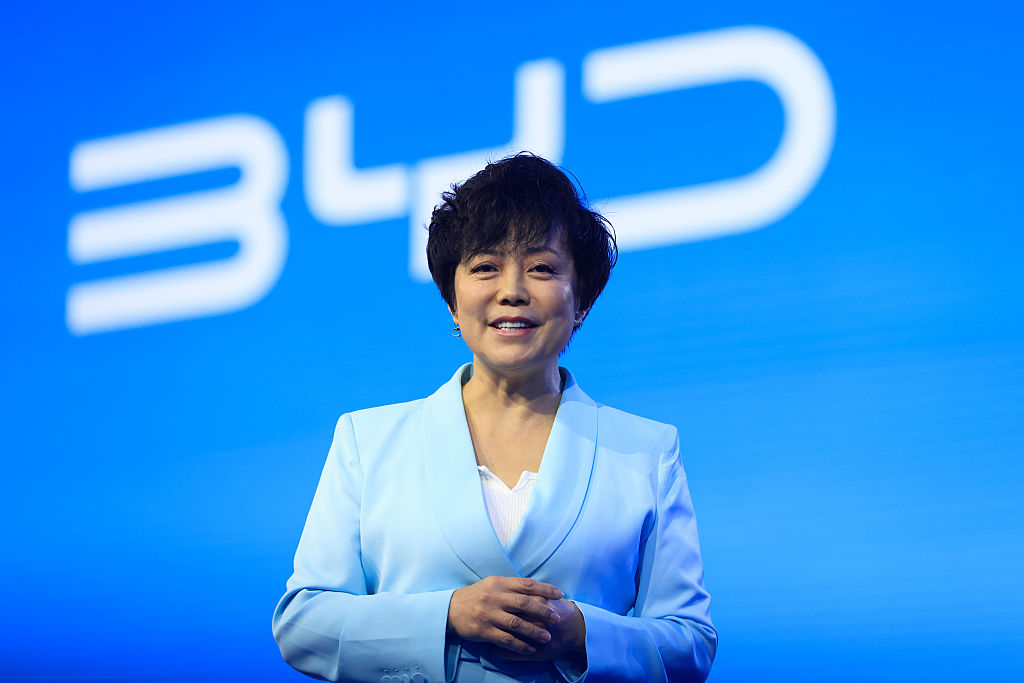

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?

The Stella Show is still on the road – can Stella Li keep it that way?Stella Li is the globe-trotting ambassador for Chinese electric-car company BYD, which has grown into a world leader. Can she keep the motor running?

-

What is Bernard Arnault's net worth?

What is Bernard Arnault's net worth?We look into Bernard Arnault's net worth – how did he make his billions?

-

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?Was the VICE bankruptcy inevitable? We look into how the once multibillion-dollar came crashing down.

-

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?Warren Buffett, sometimes referred to as the “Oracle of Omaha”, is considered one of the most successful investors of all time. How did he make his billions?

-

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory right

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory rightProfiles Kwasi Kwarteng, who studied 17th-century currency policy for his doctoral thesis, has always had a keen interest in economic crises. Now he is in one of his own making

-

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all away

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all awayProfiles Outdoor-equipment retailer Yvon Chouinard is the latest in a line of rich benefactors to shun personal aggrandisement in favour of worthy causes.

-

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goods

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goodsProfiles Johann Rupert, the presiding boss of Swiss luxury group Richemont, has seen off a challenge to his authority by a hedge fund. But his trials are not over yet.

-

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket king

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket kingProfiles Alvin Chau made a fortune catering for Chinese gamblers as the authorities turned a blind eye. Now he’s on trial for illegal cross-border gambling, fraud and money laundering.