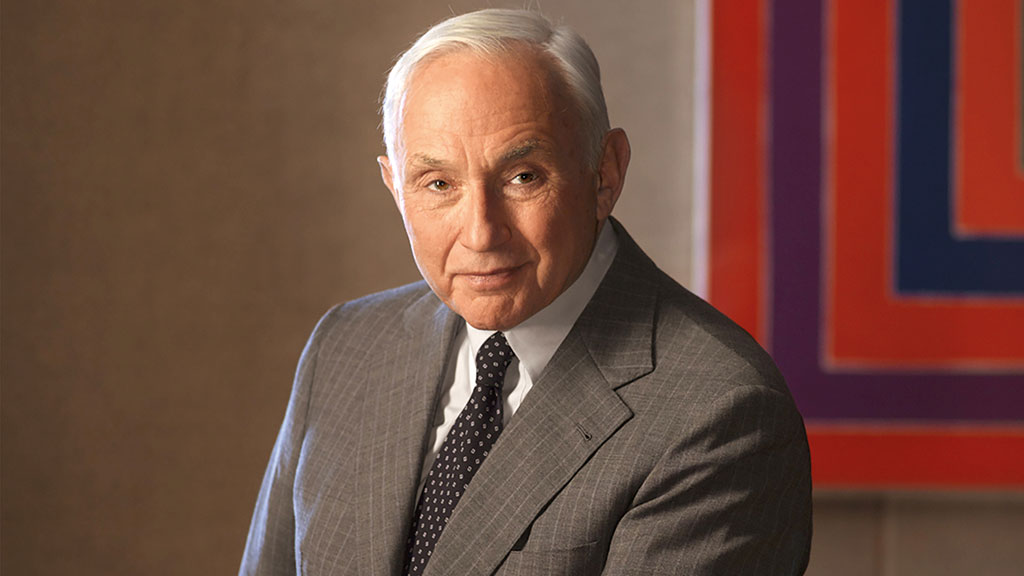

Les Wexner: the Merlin of the Mall loses his magic

Les Wexner built a retail empire from scratch and made a fortune in the process. He ended up placing his trust and many powers in the hands of disgraced tycoon Jeffrey Epstein. What went wrong?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

When Jeffrey Epstein pitched up in Les Wexner’s life in the 1980s, some of those close to him were mystified as to why “a renowned businessman in the prime of his career would place such trust in an outsider”, says The New York Times. Wexner had shrewdly built a retail empire worth billions from scratch and was hailed as “one of the country’s most influential corporate titans”. Epstein, by contrast, had “a thin resumé and scant financial experience”. And yet within a few years he had “developed an unusually strong hold” over Wexner – assuming “sweeping powers over his finances, philanthropy and private life” while driving a wedge between the Victoria’s Secret tycoon and longtime friends and associates.

A grandmaster makes his move

Wexner, now 82, praised Epstein as “a most loyal friend” with “excellent judgement and unusually high standards”. He has come to change his tune. When his former confidant was charged last year with sex-trafficking girls as young as 14, Wexner immediately “came under intense pressure” – despite emphasising that he had no knowledge of the alleged activities and had terminated his professional relationship with Epstein in 2008. News of the relationship, however, “spurred chaos” within his already struggling L Brands empire, culminating in rumours that Wexner is now “in discussions” to step down as chief executive and that parts of his conglomerate might be flogged off.

It’s hardly the swan-song Wexner must have dreamed of. After all, as recently as 2015 he was being extolled by Fortune as the “longest-serving Fortune 500 CEO” whose 50-year plus tenure at L Brands had been “a lesson in superlatives”. If you’d invested $1,000 in the company when it went public in 1969, it would be worth $62.4m today, the magazine observed. Wexner, then personally worth $7.3bn, had achieved the feat “by surveying the retail industry as a grandmaster would a chessboard, timing the acquisition and sale of brands with impeccable precision”. What a remarkable feat for an Ohio “bra salesman”.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Wexner grew up in the rag trade, setting up on his own in 1963. By 1974, he’d built a national chain with 48 stores. But the most important acquisition of his career took place in 1982 when he bought an obscure chain of six lingerie shops named Victoria’s Secret. “He built it into a global behemoth that for decades would define many Americans’ perceptions of female sexiness” – helping to reshape the US shopping mall in the process, notes The New York Times. By the end of the decade, Wexner was known as the “Merlin of the Mall”.

In Epstein’s hands

Wexner’s “lascivious empire”, as the FT calls it, offered a potential treasure trove of young female contacts for his former personal adviser. Yet by the time Jeffrey Epstein was done with Wexner, he’d acquired a good deal more besides, says The New York Times. After grabbing full “power of attorney” in 1991, property that ended up in Epstein’s hands included parts of an upscale real-estate development in New Albany, Little Saint James Island in the Virgin Islands and a huge New York City mansion. A business controlled by Epstein later obtained the (eventually notorious) Boeing 727 originally owned by The Limited. Under Epstein’s influence, the Wexner Foundation even ended up suing Wexner’s mother, Bella. “If my client needs protecting – sometimes even from his own family – then it’s often better that people hate me, not the client,” Epstein told Vanity Fair in 2003. Prophetic words.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Jane writes profiles for MoneyWeek and is city editor of The Week. A former British Society of Magazine Editors (BSME) editor of the year, she cut her teeth in journalism editing The Daily Telegraph’s Letters page and writing gossip for the London Evening Standard – while contributing to a kaleidoscopic range of business magazines including Personnel Today, Edge, Microscope, Computing, PC Business World, and Business & Finance.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?

VICE bankruptcy: how did it happen?Was the VICE bankruptcy inevitable? We look into how the once multibillion-dollar came crashing down.

-

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?

What is Warren Buffett’s net worth?Warren Buffett, sometimes referred to as the “Oracle of Omaha”, is considered one of the most successful investors of all time. How did he make his billions?

-

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory right

Kwasi Kwarteng: the leading light of the Tory rightProfiles Kwasi Kwarteng, who studied 17th-century currency policy for his doctoral thesis, has always had a keen interest in economic crises. Now he is in one of his own making

-

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all away

Yvon Chouinard: The billionaire “dirtbag” who's giving it all awayProfiles Outdoor-equipment retailer Yvon Chouinard is the latest in a line of rich benefactors to shun personal aggrandisement in favour of worthy causes.

-

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goods

Johann Rupert: the Warren Buffett of luxury goodsProfiles Johann Rupert, the presiding boss of Swiss luxury group Richemont, has seen off a challenge to his authority by a hedge fund. But his trials are not over yet.

-

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket king

Profile: the fall of Alvin Chau, Macau’s junket kingProfiles Alvin Chau made a fortune catering for Chinese gamblers as the authorities turned a blind eye. Now he’s on trial for illegal cross-border gambling, fraud and money laundering.

-

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzy

Ryan Cohen: the “meme king” who sparked a frenzyProfiles Ryan Cohen was credited with saving a clapped-out videogames retailer with little more than a knack for whipping up a social-media storm. But his latest intervention has backfired.

-

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest man

The rise of Gautam Adani, Asia’s richest manProfiles India’s Gautam Adani started working life as an exporter and hit the big time when he moved into infrastructure. Political connections have been useful – but are a double-edged sword.