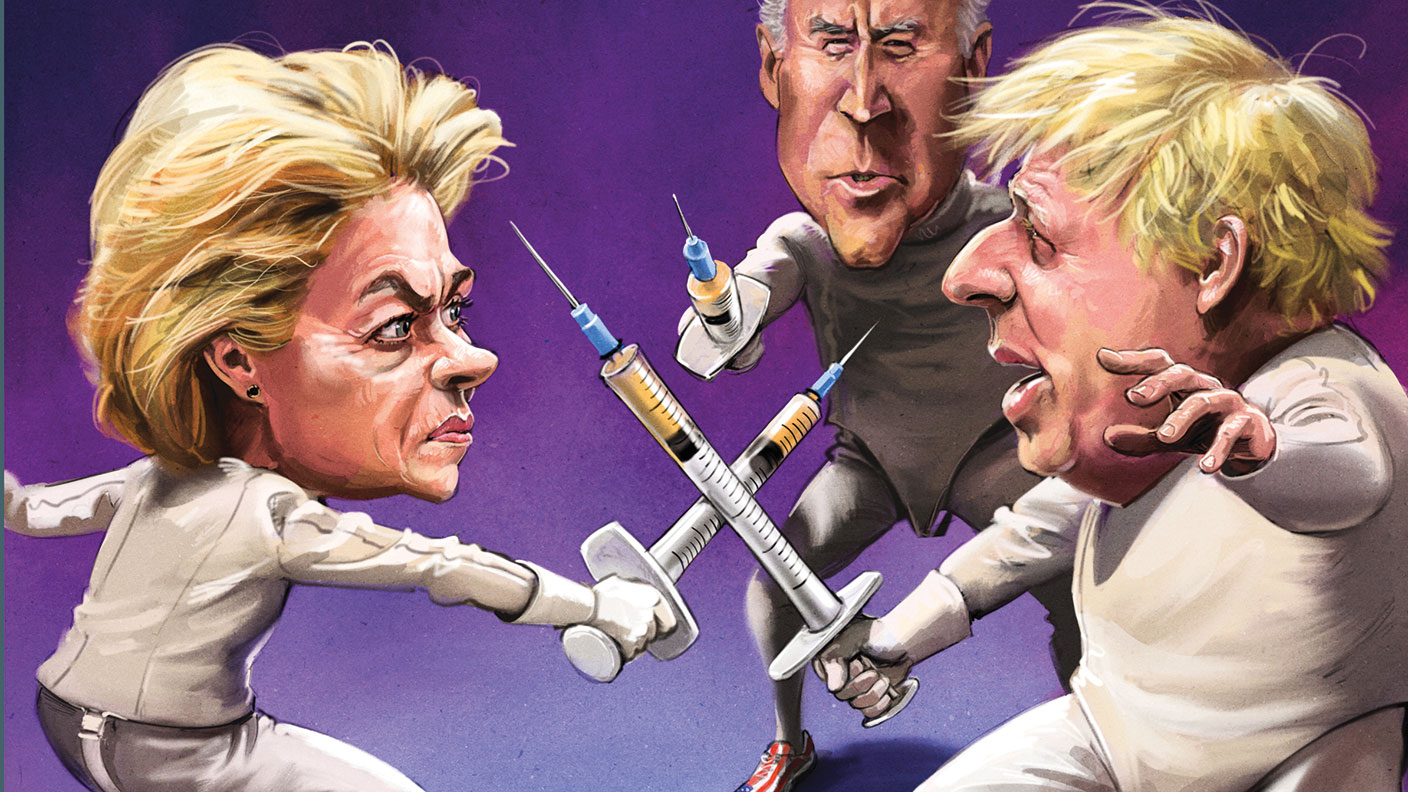

How the vaccine wars will harm us all

Grabbing and hoarding vaccine supplies, or even manufacturing one’s own, might seem to make sense for a state in an emergency. But the damage done to trust and prosperity will be huge.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What’s happened?

The threat of an all-out vaccine war between Britain and the EU appeared to recede this week, with both Boris Johnson and German leader Angela Merkel trying to calm tensions and remember “international interdependencies”. But the spectre of “vaccine nationalism” is still haunting Europe, following Ursula von der Leyen’s threat last week of emergency EU controls on vaccine production and distribution to meet the “crisis of the century”. The European Commission president suggested halting exports to countries that did not reciprocate in allowing jabs to flow to the EU, and even activating Article 122 of the EU’s treaty, which authorises emergency measures (in times of war or civil emergency) to control the distribution of essential goods. The British foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, hit back, condemning the “brinkmanship”. But the story is far from over, and this week the EU said “all options remain on the table”.

Is this just about Europe?

No, it’s a global issue. In America, vaccine makers must honour their US official contracts first before exporting. Until last week there was an absolute US ban on all Covid-19 vaccine exports, and on the equipment and ingredients needed to produce the jabs. “Only grudgingly has it agreed to start exporting batches to Canada, which had pre-ordered more jabs per head than anywhere in the world but has struggled to get delivery,” says Jeremy Warner in The Daily Telegraph. India is also cutting back on its contracted exports to the UK in the face of a resurgence in Covid-19 cases there. The pandemic is a “shared global catastrophe”, says Warner – and the vaccines that offer solutions are “the product of deeply integrated and extensive global supply chains”. How ironic, then – and yet how dispiritingly predictable – that the challenge is “driving nations further apart in an every-man-for-himself scramble”.

How international are the supply chains?

Britain relies on Covid-19 vaccine exports from the EU; ten million doses between 30 January and 16 March alone. But within the EU alone, more than 30 plants from Sweden to Spain are involved in producing the vaccines. AstraZeneca alone has manufacturing capacity in 25 sites across 15 countries. The US firm Moderna produces vaccine ingredients in Switzerland, fills and finishes the doses in Spain, and ships from there to all buyers outside the US. Pfizer, too, has all non-US production situated inside the EU. But one of the vital ingredients of the Pfizer vaccine arrives from a Croda International plant in South Yorkshire. All this explains the growing fears over a slide towards protectionism, and a rejection of comparative advantage as the governing idea of international trade. It’s often said there are no winners in a trade war, says Ross Clark in The Spectator. “But in this case there would be a very clear winner”: the virus that causes Covid-19.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

What is comparative advantage?

It’s the ability of a country (or a firm, or other economic actor) to produce a particular good or service at a lower opportunity cost than its trading partners. Two centuries ago, economist David Ricardo posited comparative advantage to show how all countries benefit if each one focuses on what they are “comparatively” good at, provided they are free to trade with each other. But although comparative advantage is one of the building blocks of modern economics, it is counter-intuitive and not easy to grasp. In the context of Covid-19, building up global vaccine capacity makes obvious sense, so one might assume all countries should try to get good at it to protect their national interests. But economic theory tells us that would be inefficient and counter-productive, and deliver worse results.

But states want to go it alone anyway?

Very possibly. The lesson the British government is taking from this crisis is the importance of domestic production, says James Forsyth in The Times. If, in a crisis, you “can’t be certain that even fellow free-market democracies will honour contracts”, then you “have to make sure that essential medical supplies are manufactured here”. The havoc wrought by coronavirus has concentrated minds on “unexpected shocks and the national vulnerabilities created by complex global supply chains”, says Philip Stephens in the Financial Times. Where once governments prized “agility” – and just-in-time delivery across borders promised ever greater prosperity – today all the talk is of “resilience” and “sovereignty”. As such, the virus has accelerated an existing trend, in play since at least the 2008 financial crisis. That’s understandable: the virus may be global, but all politics is local, and “rising populism has left governments in a defensive crouch”. But it’s also dangerous if it drives the world towards protectionism, and nations towards the economic cul-de-sac of “self-sufficiency”. There are no local fixes for this virus, and nations first over the vaccine finish line will not escape the economic consequences of failing to vaccinate developing nations.

What consequences?

Various economists have attempted guesstimates. One startling recent study commissioned by the International Chamber of Commerce projected that “the global economy stands to lose as much as $9.2trn [global GDP in 2019 was $88trn]if governments fail to ensure developing economy access to Covid-19 vaccines” – and that as much as half of that hit would fall on advanced economies. Reports by Rand Europe and the Eurasia Group offered similar conclusions. Such figures are necessarily speculative, but suggest the scale of the issue. The most grave damage done by this crisis will be to the “global ecosystem” based on co-operation and trust that is essential for prosperity and progress, says William Hague in The Daily Telegraph. If we can’t rise above the temptations of vaccine nationalism, we will be paying a “very high” price for decades to come.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?