Forget austerity – governments and central banks have no intention of cutting back

Once the pandemic is over will we return to an era of austerity to pay for all the stimulus? Not likely, says John Stepek. The money will continue to flow. Here’s what that means for you.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“Generals fight the last war”, so the old saying goes. The same goes for central banks and governments when it comes to recessions. They're always looking over their shoulder at the most recent economic crisis.

“We won't do that again”, they think, diligently nailing a board across the door of the empty stable, while the rear end of the horse canters away into the far distant sunset. And in doing so, they almost always sow the seeds of the next financial crisis. Which is exactly what's happening now.

Are we heading for bust or boom?

A quick recap: markets are currently in the grip of confusion. When Covid-19 goes away, will it leave behind an economic wasteland, laden with debt, struggling with mass unemployment, and where psychologically-scarred consumers hoard what few pennies they can amass against a future storm?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Will we continue to live in a world dominated by tech companies, secular stagnation, and disinflationary forces, or will we see a huge rebound in demand as consumers, cushioned by government measures to offset the worst economic impacts of the virus, desperately try to catch up on everything they've missed over the past year?

And what if this demand then butts up against disrupted supply chains and producers who've slashed activity and now have to rush to catch up? Investors will need to position for inflation and surging demand for real resources instead. No wonder markets are confused. Those are two very different outcomes. And they depend to an extent, on what central banks and governments do.

This is where we are now. You might have noticed that there are two camps here as well. One camp suggests that governments will want to pay back the debt via some form of austerity (“austerity” can mean spending cuts or tax rises or both – all that matters is that the government takes more money out of the economy than it puts back in). They also argue that central banks will raise interest rates (or at least stop printing money) as soon as there's any hint of inflation getting out of control. Logic suggests – to this group at least – that either we'll end up in a disinflationary environment, or that we'll get a “Goldilocks” reflation, where governments and central banks manage the economy's finances for a near-perfect post-Covid comeback.

The other camp says that the whole political argument has changed. “Austerity” is a dirty word following the post-2008 experience. “MMT” is the new buzzword: deficits don't matter, and all that matters is inflation, so politicians won't cut spending in a hurry. Same goes for central banks – they've spent more than a decade trying to get inflation into the economy. If you think they care about overshooting a 2% target now, you're blind to the past ten years.

Needless to say, I'm in the second camp here. And I feel that events in the US yesterday make it clear that it's the right one to bet on.

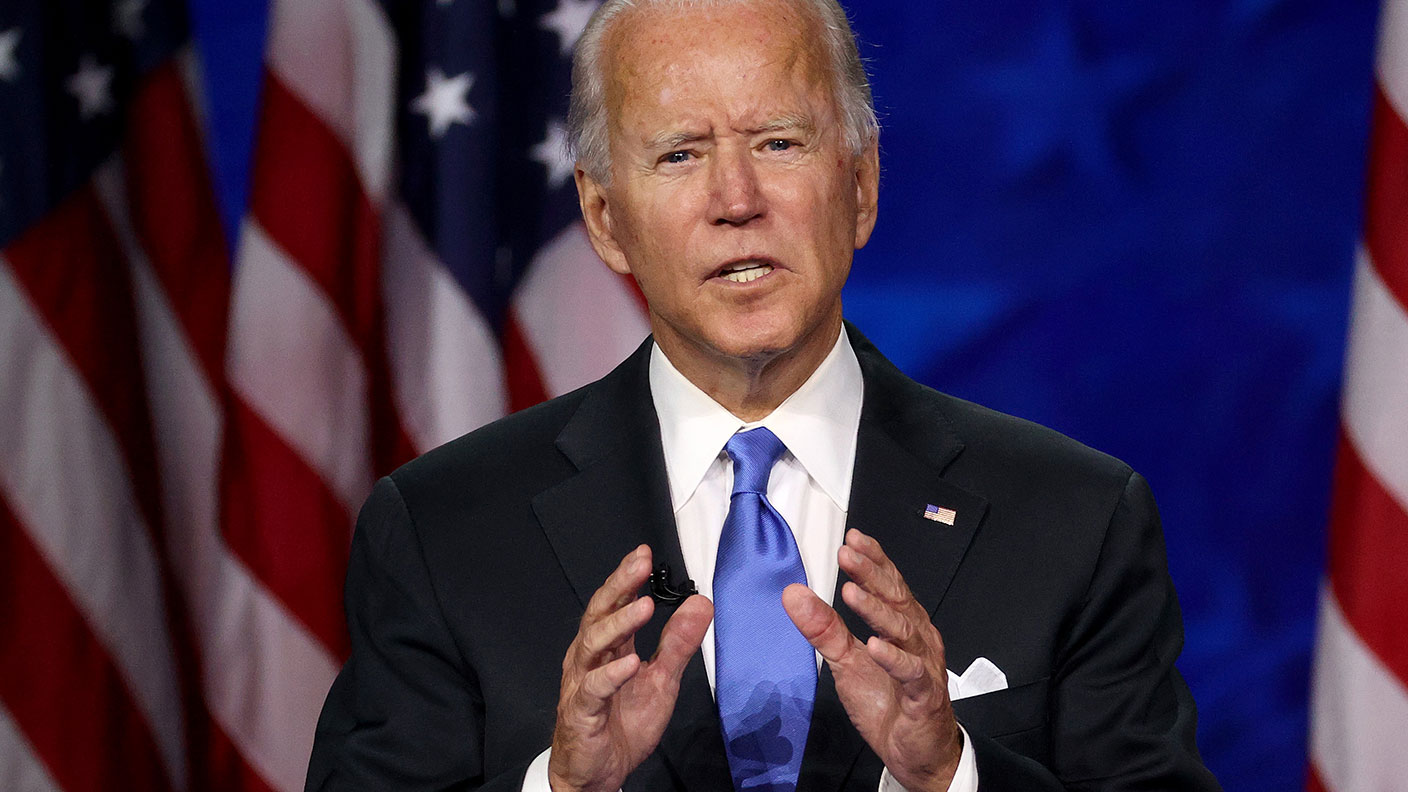

Biden and Powell will keep the money flowing whatever happens

On the government side, we had Joe Biden giving us an outline of what he wants to do when he takes charge in the US. He's looking for just under $2trn to spend on a new Covid relief package. US households got $1,800 each in last year's relief package; Biden wants to send them another $1,400. Moreover, there'll be another $400 a week in Federal unemployment benefits on top of those supplied by individual states.

Remember, this is direct fiscal stimulus. It's not filtered through banks who need to persuade people to borrow it. This is new, no-strings-attached money going into the pockets of individuals.

Meanwhile, Biden also wants to spend on speeding up the vaccine roll-out. That's a trickier thing to get done (it relies on sufficient competence at far too many levels), but any acceleration in the process brings forward the day that the economy can re-open, which in turn lessens the overall damage.

As Bloomberg notes, “the risk of doing too little is far greater than going too big, a Biden official said. The incoming president last week highlighted that historically low interest rates offer space for the US to use deficit spending to strengthen the economy now.” That's not the sound of a man watching the pennies, or planning to do so any time soon. The only real barriers to greater spending are that Biden might struggle to get it past US politicians, what with all the other business going on, in particular the impeachment of the outgoing president.

But then there's the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank. Current chair Jerome Powell was also making speeches yesterday. And he's very keen to emphasise that the Fed has learned its lesson from 2008 and 2013 and all the other times it tried to stop pumping money into the system a bit too early (ie ever).

“Now is not the time to be talking about exit”, he said, gently slapping down some other members of the Fed's monetary-policy-setting committee who have hinted at printing less money if inflation takes off. That, he said, is “another lesson of the global financial crisis... be careful not to exit too early.”

What does it boil down to? As John Authers puts it in his Bloomberg newsletter, “if the Fed makes a mistake, it looks like it will be to wait too long before preparing to exit.” Eventually I suspect that'll lead us beyond Goldilocks and into much-higher-than-expected territory for inflation. It might even happen quite quickly. It's one more reason to hold onto the gold in your portfolio, even if it isn't quite as exciting as the asset that some consider to be the pretender to its throne – bitcoin.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?Analysis High inflation means take home pay is being eroded in real terms. An online calculator reveals the pay rise you need to match the rising cost of living - and how much worse off you are without it.