Are we back on the road to serfdom?

The coronavirus crisis has led to levels of state intervention unprecedented in peace time. The Austrian School reminds us of the challenges, say Dan Greenwood and Stuart Watkins.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

By Dan Greenwood and Stuart Watkins

This year marks the centenary of the publication of “Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth”, an essay by Ludwig von Mises that began the so-called “socialist calculation debate”, a fundamentally important, long-standing argument among scholars of economics and politics about whether socialism is possible.

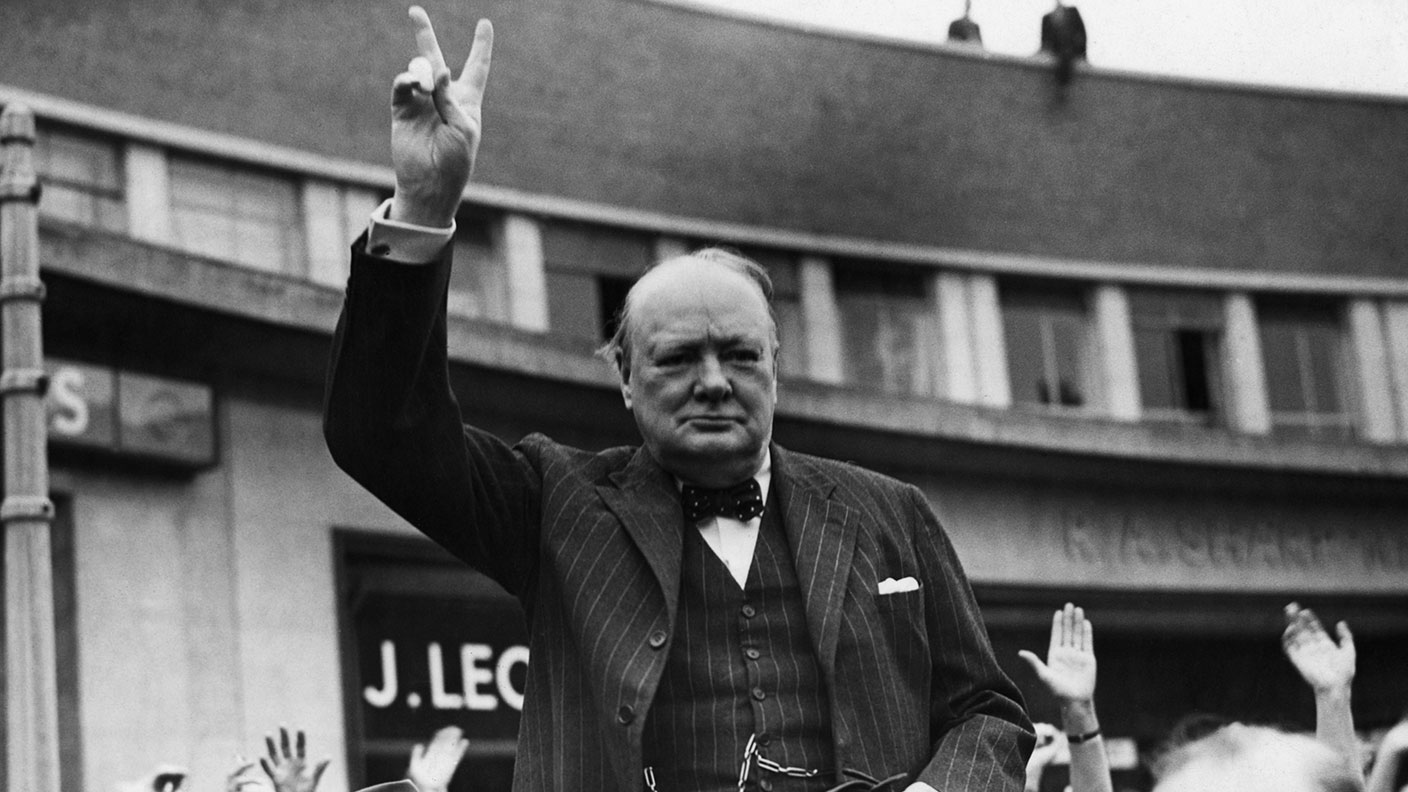

That might sound rather arcane and indeed the debate remains barely known outside of academia and political circles of the radical left and libertarian right. Given that the debate was especially concerned with the feasibility of a global communist system that had abolished trade and money, you may wonder what relevance it can possibly have given that few advocates of socialism or social democracy these days envisage the kind of centrally planned, entirely non-market communism sought by the Bolsheviks and stringently critiqued by Mises and his fellow Austrian School economist Friedrich Hayek. A closer look at Mises’ arguments, however, reveals that they remain pertinent. In the 1945 election, Winston Churchill famously paraphrased Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom and worried about the consequences of electing a Labour government committed to socialising the economy. Today in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, which has seen a massively expanded role for the state, we would do well to remind ourselves of these arguments.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Why socialism doesn’t work

Mises and Hayek were classical liberals who believed that the state should have a strictly circumscribed role – primarily that of enforcing private property rights, supplying a minimal range of public goods, as well as minimal welfare provision only for those in most severe need – in a broader context of private ownership and free markets. Socialists and social democrats today, while not necessarily advocating full communism instead, would see the last 100 years as providing strong grounds for challenging the wisdom of this.

Inequalities of wealth and income, severe economic crises and ecological destruction would seem to challenge the idea that such a system inevitably leads to the best of all possible worlds. The profundity of market failures and the vital importance of public goods that cannot be provided through the market alone is widely recognised, not least in the current public-health crisis. The rapidity with which the state had to step in and take control of everything from the railways to paying workers’ wages in the wake of the spread of the coronavirus would seem to have placed the Austrian case for markets under significant strain.

Yet as the economic calculation debate of 100 years ago highlighted, the case for classical liberalism is based upon some deep and compelling arguments, the force of which has been underestimated by the left. They need to be kept in mind even at a time when there is a strong imperative for state intervention and planning in the heat of a crisis.

Mises and Hayek saw their scholarly role in terms of developing ideas that would percolate through society. Their ideas, which evolved in the course of the calculation debate, did indeed pass into our everyday understanding of markets as indispensable drivers of economic efficiency and innovation. We are used to hearing these arguments rehearsed when politicians pursue the privatisation of industries, for example, or hear them deployed against those who seek nationalisation. Alongside this more familiar case for markets, the Austrians developed a stringent critique of central planning and more generally of state intervention to achieve social goals.

Perhaps the more familiar aspect of that critique has to do with incentives – that only market processes can reliably establish the incentives required for achieving economic efficiency. We can rely on entrepreneurs to solve problems for us as they are motivated to act by the prospect of profit and are spurred on to greater heights by competition. We can rely on the world’s workers getting out of bed on time if the monetary reward is sufficient. A non-market, planned economy would lack such incentives, the argument goes.

This idea gained prominence with the rise of “public choice theory”, which assumes that political actors, like economic ones, are self-interested individuals acting rationally to maximise satisfaction. This model seemed to explain well at least some of the failures we have come to associate with government control, such as corruption and inefficiencies. Mises and Hayek, however, writing at a time of large-scale socialist movements and indeed revolution, recognised the need to avoid relying entirely upon this argument. What if people with non-monetary incentives and impeccable intentions were in charge, say? Mises and Hayek’s claim was stronger – that attempts to plan an economy without markets, however well-intentioned and motivated the planners might be, would inevitably fail due to the complexity of modern economies.

The knowledge problem

As Hayek in particular emphasised, the fundamental problem for a socialist economy concerns knowledge. The highly decentralised market process of exchange and price generation captures and communicates a vast amount of dynamically changing knowledge, responding to highly complex and ever-changing demand and supply levels and reflecting the locally situated goals and decisions of individuals across society. By contrast, state planning, even at a local scale and most certainly at national and international level, necessarily involves an element of centralisation. Attempting to achieve coordination of knowledge of the kind facilitated by markets is a profound problem for non-market planning. Decision-making is more susceptible to unforeseen consequences and failures to capture important local knowledge and expert insights. Hayek’s view of the inevitable error and arbitrariness of state interventions being a road to dictatorship and serfdom may be exaggerated, as many critics have argued. But his articulation of this “epistemological” challenge raises questions of vital relevance to contemporary governance where the aim is to shape market outcomes rather than remove markets entirely.

Hayek’s philosophical approach challenges the rationalistic presumption, evident across the political spectrum, that politicians can straightforwardly access technocratically defined solutions to social problems. Such assumptions may now be more widespread than ever, explaining, at least in part, current scepticism about politicians as they inevitably fail to deliver what they imagine and promise they can achieve. Austrian scepticism was not a postmodernist rejection of the potential for social progress, but rather a call to recognise the need for a political economy that fosters processes of knowledge discovery and innovation in the face of complexity and uncertainty.

Anthony Giddens’ famous vision of the “third way” tried to marry Hayek’s insights with social-democratic ambitions to correct for perceived market failures. New Labour’s programme aimed to put those ideas into practice, promoting state engagement with the private and third sectors in an effort to overcome Hayek’s epistemological challenge. Where markets could not solve social and economic problems of society, ways were tried to mimic market competition. Yet this entailed some new, often problematic forms of technocracy. Performance measures and targets were imposed in a range of fields, from health and education to climate-change mitigation and social care. These were, as we now appreciate all too well, far from a complete success, to say the least. As Hayek warned, performance measures established outside of the market run the risk of failing adequately to capture public value, leading to unintended consequences.

New Labour’s performance measures created perverse incentives and led to the gaming of targets – for example, schools manipulated exam results to meet their targets; ambulance drivers delayed patients’ entry to A&E to keep within maximum waiting limits once inside; police priorities were skewed to focus on the crimes most easily solved. The response to such failings, some of which have persisted or taken new forms under the Conservatives, need not be sceptical rejection of targets as such, however, but might instead be a search for new, smarter forms of intervention – ones that appreciate and seek to respond to Hayek’s insights.

The challenges states face today of protecting public health, promoting ecological sustainability and stabilising the climate are unprecedented. Profound inequalities remain entrenched. But just how can state capacity be improved and the failings of markets corrected for, in the face of complexity? The Austrians’ philosophical perspective cautions us against simplistic assumptions that introducing any particular set of targets or regulations will be the answer. Fundamental threats to human life and security in the coronavirus crisis create the need for public goods, but delivering them requires a careful balancing of profoundly difficult trade-offs and uncertainties that we hear about every day, and which are not entirely measurable either by money or any other quantitative measure. Mises and Hayek are famous as advocates of free markets, but their arguments were founded on a fundamental recognition of the profound limitations of any form of decision-making, market or otherwise, in the face of the countless, continually changing array of individual priorities and economic choices across society.

An open question

None of this is to dismiss the case for state intervention in some circumstances. But the question of the most suitable forms of intervention in different contexts is best viewed as inevitably an open one. Politicians go wrong when they see their task as being to promise and then deliver pre-given solutions, rather than constructing frameworks within which socially dispersed knowledge can be discovered, captured and put to use. The Corbyn Labour party, for example, was quick to advocate specific kinds of state intervention as the solution to social problems, but reflection on the complexities involved and the dangers inherent in central planning had seemingly vanished entirely.

Mises’ century-old challenge should spur a rethink about how states can effectively achieve goals that will not be secured by markets. Latter-day Lenins may be sad to learn that, in all but the most adventurous and unlikely scenarios, money and markets, or something very like them, will continue to play an important role. We can all gain from reflecting on the reasons why.

• Dr Dan Greenwood is Reader in Politics at the University of Westminster. His book, Effective Governance: Complexity, Coordination and Discovery, is published by Palgrave early next year

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Stuart graduated from the University of Leeds with an honours degree in biochemistry and molecular biology, and from Bath Spa University College with a postgraduate diploma in creative writing.

He started his career in journalism working on newspapers and magazines for the medical profession before joining MoneyWeek shortly after its first issue appeared in November 2000. He has worked for the magazine ever since, and is now the comment editor.

He has long had an interest in political economy and philosophy and writes occasional think pieces on this theme for the magazine, as well as a weekly round up of the best blogs in finance.

His work has appeared in The Lancet and The Idler and in numerous other small-press and online publications.

-

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?Whether you’re an ISA investor seeking reliable returns, looking to add a bit more risk to your portfolio or are new to investing, MoneyWeek asked the experts for funds and investment trusts you could consider in 2026

-

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continue

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continueIt was another difficult year for fund inflows but there are signs that investors are returning to the financial markets

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?

Is my pay keeping up with inflation?Analysis High inflation means take home pay is being eroded in real terms. An online calculator reveals the pay rise you need to match the rising cost of living - and how much worse off you are without it.