A weakening US dollar is good news for markets – but will it continue?

The US dollar – the most important currency in the world – is on the slide. And that's good news for the stockmarket rally. John Stepek looks at what could derail things.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

As we’ve said many times before in Money Morning, the US dollar is one of the most important – if not the most important – prices in the world.

Right now, the US dollar is on the slide. That’s good news, for reasons we’ll reiterate in a moment. A falling US dollar keeps the “reflation” trade intact and means asset prices are likely to keep rising.

So what – if anything – could derail this?

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Here’s why the US dollar matters so much

Why is the US dollar so important? It’s because everyone needs US dollars. Close to 90% of all currency trading in the world involves the US dollar. Any widely traded good or commodity you care to mention is primarily priced in US dollars.

You can think of the US dollar as the oil that lubricates the machinery of global trade, or as the operating system on which global finance runs. In short, it’s the global reserve currency. One day, that might change. It has in the past. But that’s not today’s topic. Today we’re looking at far shorter-term issues.

So we’ve established that everyone needs US dollars. A logical extension of this point is that a weaker US dollar is in fact a good thing for markets and for the global economy. If the dollar is weak, then the dollar is cheap. If the dollar is cheap, that means there’s more of it around, it’s easy to get hold of when needed, and there clearly aren’t lots of people running around panicking trying to get hold of US currency.

Put even more simply, w

hen the US dollar is cheap, global monetary conditions are nice and loose. That’s good for risk assets (like equities, for example) and in particular emerging markets, whose need for US dollars makes them more vulnerable to spikes in the exchange rate. Right now, the US dollar is not especially cheap or expensive relative to history. But the good news is that it is getting cheaper.

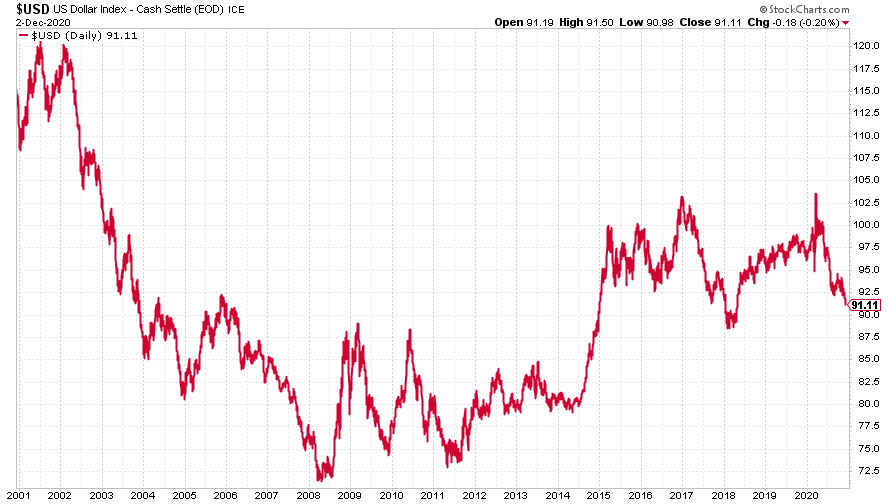

The easiest way to look at the US dollar is via the DXY – a measure of the value of the US currency against a basket of the currencies of its biggest trading partners. Below, courtesy of Stockcharts.com, is a chart of the US dollar index going back for 20 years.

You can see that during the easy credit era running up to the global financial crisis, the dollar grew persistently weaker (note the little rebound in 2005 which was a brief period when it looked as though the party might end early, before everyone got back to the punchbowl again). As credit dried up, you can see that the US dollar spiked higher in 2008. Then during the post-2008 recovery process, the dollar fluctuated but on a broader view was flat, before taking off higher towards the end of 2014, as the European Central Bank (ECB) finally embarked on quantitative easing.

Why was this so significant? Because the euro is the world’s second-most widely-used currency. It’s a long way behind the dollar, but it represents the biggest weighting in the DXY basket. So when the euro goes up or down against the dollar, it has a big impact on the chart above. We’ll return to this in a moment.

But in any case – for most of Donald Trump’s time as president, the dollar has mostly been really pretty strong (above 100 in 2017 and at the start of this year, as Covid-19 produced a spike in demand for US dollars) but not quite strong enough to cause major problems. Ironically for Trump, it now looks as though Joe Biden will be getting what he, Trump, always wanted – a structurally weaker dollar. In all, that’s good news for risk assets and the whole “reflation” post-Covid trade. So what’s going on and what could throw a spanner in the works?

Why the European Central Bank will struggle to stop the euro from rising against the dollar

As hinted at in the chart above, one big factor in the dollar weakening has been the euro strengthening. Most of this is driven by differences in interest rates and rate expectations. But there are other factors too. One issue that has hung over the euro and kept it weak in recent years is the concern that it simply won’t survive. However, that fear is all but gone from the market now. That has helped the euro to rally in recent months.

However, the ECB won’t necessarily be happy about that. The persistent problem in the eurozone is that it has to make monetary policy for a set of diverse economies. Some (small, tourist-dependent economies like Greece and Portugal) need a weaker currency, while others (leading global economies like Germany) really should have stronger currencies.

When the US was recovering fast post-2014 and thinking of raising interest rates, while Europe was only just getting around to QE, it was easy to keep the euro weak. Conditions just aren’t the same today. And what makes things even trickier is that the eurozone is returning to its old habits – the need for political consensus means it is struggling to do things like push recovery budgets through, and take the sorts of aggressive monetary action that would be needed to keep a lid on the currency.

In turn, that means you’ve got a situation where markets can see a world in which the US does a lot of public spending, while the eurozone struggles to get much done. That’s not ideal for eurozone economies, but arguably if it helps us to stay on the path to a weaker dollar, it’s certainly good news for emerging markets.

The question is: will the ECB attempt to do something about it? The ECB has voiced concern about the euro rising above $1.20 in the past. But it’s now above $1.21, so there’s only so much that “jawboning” can achieve. There is another meeting of the ECB later this year – next Thursday in fact. They’d have to do something quite drastic to ignite the currency wars again and it’s unclear whether they’d have sufficient backing to do so.

So it looks for now, certainly, that the dollar weakness will continue unabated. That’s good news for the rally. Of course, in the longer run, it is possible for the dollar to get too weak – lots of countries export goods to America and they don’t want their currencies to rise against the dollar as a result. But for now, we’re a while away from that point.

In short, stick with the reflation trade. If you want to know how to play it, pick up the next issue of MoneyWeek, out tomorrow. (And get your first six issues free here if you don’t already subscribe).

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Hints of private credit crisis rattle investors

Hints of private credit crisis rattle investorsThere are similarities to 2007 in private credit. Investors shouldn’t panic, but they should be alert to the possibility of a crash.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Why you should keep an eye on the US dollar, the most important price in the world

Why you should keep an eye on the US dollar, the most important price in the worldAdvice The US dollar is the most important asset in the world, dictating the prices of vital commodities. Where it goes next will determine the outlook for the global economy says Dominic Frisby.

-

What is FX trading?

What is FX trading?What is FX trading and can you make money from it? We explain how foreign exchange trading works and the risks

-

The Burberry share price looks like a good bet

The Burberry share price looks like a good betTips The Burberry share price could be on the verge of a major upswing as the firm’s profits return to growth.

-

Sterling accelerates its recovery after chancellor’s U-turn on taxes

Sterling accelerates its recovery after chancellor’s U-turn on taxesNews The pound has recovered after Kwasi Kwarteng U-turned on abolishing the top rate of income tax. Saloni Sardana explains what's going on..

-

Why you should short this satellite broadband company

Why you should short this satellite broadband companyTips With an ill-considered business plan, satellite broadband company AST SpaceMobile is doomed to failure, says Matthew Partridge. Here's how to short the stock.

-

It’s time to sell this stock

It’s time to sell this stockTips Digital Realty’s data-storage business model is moribund, consumed by the rise of cloud computing. Here's how you could short the shares, says Matthew Partridge.

-

Will Liz Truss as PM mark a turning point for the pound?

Will Liz Truss as PM mark a turning point for the pound?Analysis The pound is at its lowest since 1985. But a new government often markets a turning point, says Dominic Frisby. Here, he looks at where sterling might go from here.

-

Are we heading for a sterling crisis?

Are we heading for a sterling crisis?News The pound sliding against the dollar and the euro is symbolic of the UK's economic weakness and a sign that overseas investors losing confidence in the country.