Are we heading for a sterling crisis?

The pound sliding against the dollar and the euro is symbolic of the UK's economic weakness and a sign that overseas investors losing confidence in the country.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“Financial markets express their faith – or lack of it – in a country” through its borrowing costs and the value of its currency, says Russ Mould of AJ Bell. In the UK, investors “do not like what they see”. On Monday the pound slumped close to its lowest level against the dollar in 37 years, trading as low as $1.14.

Rapid interest-rate hikes in the US have seen the greenback strengthen against most currencies this year – it recently hit a 24-year high against the Japanese yen. But sterling has done especially poorly of late. In August the pound lost 4.5% against the dollar, its worst monthly performance since October 2016, and also fell almost 3% against the euro.

The pound’s fall comes despite the fact that the Bank of England has been raising interest rates, a move that would normally strengthen a currency. “Until August, there had never been a month when sterling fell by as much as 4.5% against the dollar and ten-year gilt yields rose by more than 90 basis points,” according to data going back to 1971, say William Schomberg and Dhara Ranasinghe on Reuters.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The fact that gilt yields are rising (see below) even as the currency falls “is indicative of overseas investors losing confidence in the UK”, says Mike Riddell of Allianz Global Investors. “I think the UK and the gilt market are in a degree of danger.”

A toxic cocktail

Traders are reacting negatively to Liz Truss’s proposed “cocktail of especially loose fiscal policy, attacks on the central bank and conflict with the EU”, says Hugo Dixon on Reuters. If she’s not careful “the pound could be clobbered”. Truss is not alone in wanting to spend more on the energy crisis, but the trouble is that the UK is especially vulnerable to inflation, says Ian Johnston in the Financial Times.

Core inflation is running at 6.2% here, compared with 4% in the eurozone. That means that “pound for pound, euro for euro, fiscal spending by governments will be more inflationary in the UK” than elsewhere in Europe, says Antoine Bouvet of ING. The UK’s large current-account deficit – which hit £44.2bn, or 7.1% of GDP, on an underlying basis in the first quarter – leaves it vulnerable to the whims of financial markets. The gap needs to be covered by foreign capital.

If global investors lose confidence in Britain then a “balance of payments crisis” and sharp sterling devaluation cannot be ruled out, says Shreyas Gopal of Deutsche Bank. “We estimate trade-weighted sterling would need to fall by a further 15% to bring the UK’s deficit back to its ten-year average.” Such a scenario is not unprecedented: the UK had to turn to the International Monetary Fund for an emergency loan in 1976 following “aggressive” spending, a nasty energy shock and a decline slide in the pound.

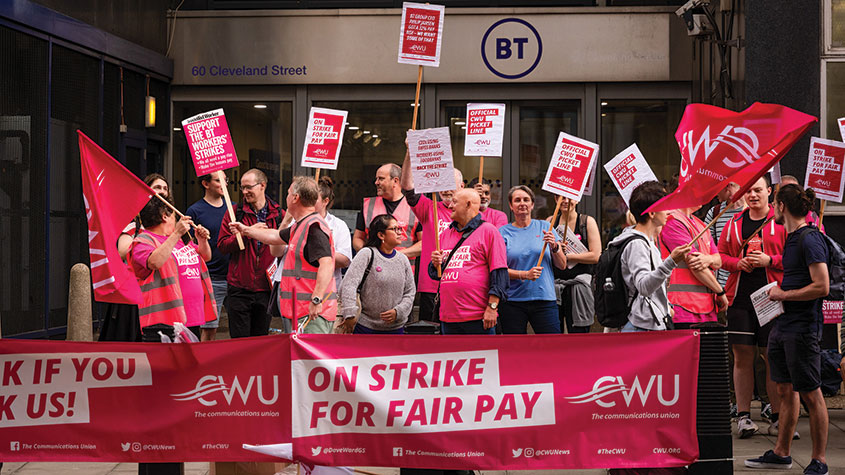

Goldman Sachs analysts recently warned that UK inflation “could soar above 22% next year”, says Liam Halligan in The Daily Telegraph. Price pressures herald an autumn of “widespread industrial action and even civic unrest”. Britain’s sliding pound risks becoming “a symbol of economic weakness and a broader lack of governance”.

The bond bear market will get worse

Ten-year UK gilt yields hit 3% on Monday for the first time since 2014. Rising yields are a reminder that there are limits to government borrowing, says The Times. With “the ratio of public debt to GDP…close to 100%, policymakers need to be wary”. For all Liz Truss’s talk of faster growth, “there is ultimately no route to national wealth by inflationary public financing and currency depreciation”.

Bond yields move inversely to prices, so it has been a miserable year for fixed income. The Bloomberg Global Aggregate Total Return index, which tracks global investment-grade government and corporate debt, has lost more than 20% since peaking last year. A decline of that magnitude marks a bear market. This is the first time the index has entered a bear market since its inception in 1990. Bear markets are “virtually unknown in bonds”, says David Randall on Reuters. Between 1990 and its January 2021 peak, the global bonds index “delivered an aggregate total return of nearly 470%”.

This year has thus proved a rude awakening, says Steve Goldstein for MarketWatch. This is likely to be “the worst year for US fixed income since at least 1928”. Bonds are widely considered to have been in a “secular” bull market since the mid-1980s, say Garfield Clinton Reynolds and Finbarr Flynn on Bloomberg. Yet soaring inflation and tighter monetary policy may have finally slain the bond bull. Bonds in Europe have led the sell-off, with a Bloomberg index that tracks investment-grade sterling bonds also falling into a bear market last week.

There could be more pain to come, says Jack Denton in Barron’s. “If there is a recession but inflation persists, forcing the Fed to keep turning the screws on financial conditions, the bond bear market might only get hairier.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Alex is an investment writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2015. He has been the magazine’s markets editor since 2019.

Alex has a passion for demystifying the often arcane world of finance for a general readership. While financial media tends to focus compulsively on the latest trend, the best opportunities can lie forgotten elsewhere.

He is especially interested in European equities – where his fluent French helps him to cover the continent’s largest bourse – and emerging markets, where his experience living in Beijing, and conversational Chinese, prove useful.

Hailing from Leeds, he studied Philosophy, Politics and Economics at the University of Oxford. He also holds a Master of Public Health from the University of Manchester.

-

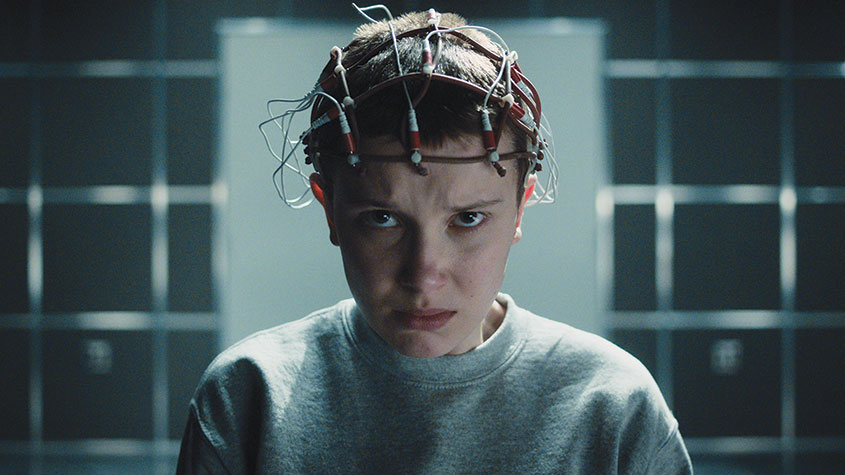

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Why you should keep an eye on the US dollar, the most important price in the world

Why you should keep an eye on the US dollar, the most important price in the worldAdvice The US dollar is the most important asset in the world, dictating the prices of vital commodities. Where it goes next will determine the outlook for the global economy says Dominic Frisby.

-

What is FX trading?

What is FX trading?What is FX trading and can you make money from it? We explain how foreign exchange trading works and the risks

-

The Burberry share price looks like a good bet

The Burberry share price looks like a good betTips The Burberry share price could be on the verge of a major upswing as the firm’s profits return to growth.

-

Sterling accelerates its recovery after chancellor’s U-turn on taxes

Sterling accelerates its recovery after chancellor’s U-turn on taxesNews The pound has recovered after Kwasi Kwarteng U-turned on abolishing the top rate of income tax. Saloni Sardana explains what's going on..

-

Why you should short this satellite broadband company

Why you should short this satellite broadband companyTips With an ill-considered business plan, satellite broadband company AST SpaceMobile is doomed to failure, says Matthew Partridge. Here's how to short the stock.

-

It’s time to sell this stock

It’s time to sell this stockTips Digital Realty’s data-storage business model is moribund, consumed by the rise of cloud computing. Here's how you could short the shares, says Matthew Partridge.

-

Will Liz Truss as PM mark a turning point for the pound?

Will Liz Truss as PM mark a turning point for the pound?Analysis The pound is at its lowest since 1985. But a new government often markets a turning point, says Dominic Frisby. Here, he looks at where sterling might go from here.

-

Netflix has plenty of life in it yet – here's how to trade the shares

Netflix has plenty of life in it yet – here's how to trade the sharesTips Netflix still has plenty of scope for growth, says Matthew Partridge, and the shares are reasonably priced. Here's how to play the Netflix share price.