House prices in the UK are still gently falling in real terms

House prices rose by 0.4% in October, and are now rising more slowly than wages or wider inflation. So, in “real terms”, they’re falling. That’s great news, says John Stepek. Here’s why.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Time's getting tight! Book your ticket to the MoneyWeek Wealth Summit on 22 November now we've just added the FT's Gillian Tett to our already stellar roster of speakers and panellists you really don't want to miss this (oh, and if you happen to need CPD, you can get six hours' worth by attending). Book now!

Nationwide has just released its latest house price figures.In October, house prices were 0.4% higher than they were a year ago. Your average UK home will now set you back £215,368 exactly. Prices are rising more slowly than wages or wider inflation. That means they're falling in "real" terms. That's great news...

Slowly falling house prices are a good thing

This morning's figures from Nationwide show that UK house prices are still pretty much flat, and falling after inflation.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The economy is OK. Interest rates are low. Employment is high. Those things are likely to prevent an all-out crash.

On the other hand, rates probably can't go much lower, while the impact of the effective removal of landlords from the housing market is still rippling through the market.

And while the resolution of Brexit might boost sentiment or activity at one level, it is also likely to lead to slightly higher interest rates, which I suspect would help to prevent a massive rebound in prices.

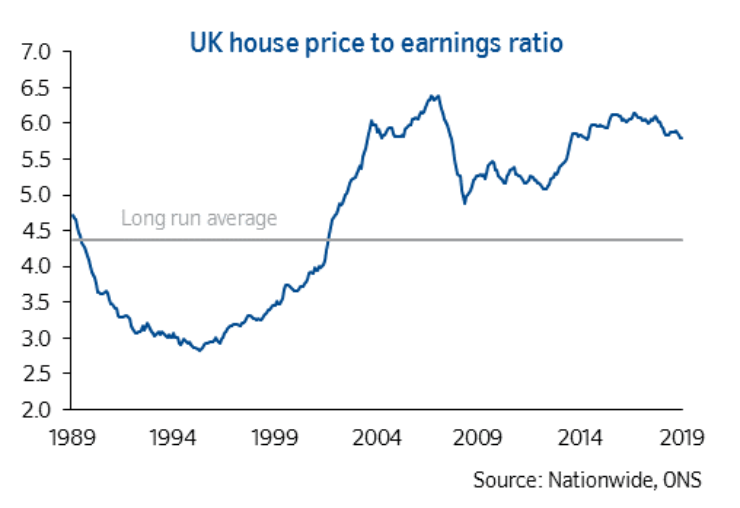

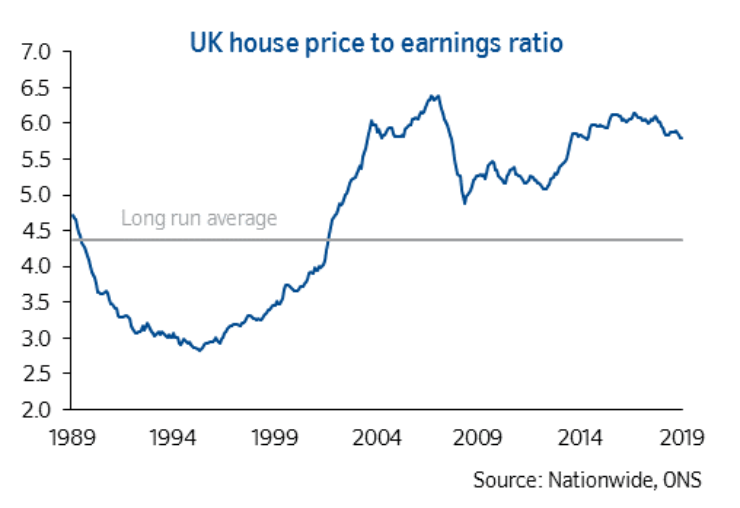

This is all good. As the Nationwide chart below shows, this means that affordability is gently improving.

I hope this continues. You've heard me say that dozens of times by now, but I like to keep reiterating it, for a couple of reasons.

One reason is that, here in the UK, we are rather attached to the idea of ever-rising house prices. I think it would be helpful for us to shed this attachment and instead recognise that hoping for a house to provide both shelter and a retirement income is a recipe for a high-stress existence.

This is unfortunately, as yet, a minority view. My colleague Merryn keeps a track via Twitter of the "how celebrities invest their money"-type interviews in the Sunday papers.

She's always very excited to spot the occasional sensible celeb who not only has a pension, but also understands that said pension holds equities. However, mostly celebs say something along the lines of "I own property. The stockmarket's just a casino. You can't go wrong with bricks'n'mortar."

There's this weird notion that investing in stocks is faintly immoral gambling, whereas taking a punt with borrowed money on the housing market (competing with people who just want a roof over their heads in the process) is honest in some way.

Anyway, once people stop making fast money from property, that will hopefully start to change.

House prices are not about physical supply and demand

The second reason stems from the other end of the spectrum. I've noticed that the tenor of columnists getting annoyed about the "housing crisis" is becoming increasingly hysterical, probably because we're coming up for an election (at some point) and housing is a political hot button.

The answer for these writers is always to "build more houses", because it's all about supply and demand. The problem is that it's not that simple.

It's interesting that we've become obsessed with the idea of building more homes at a time when in many parts of the UK outside London double-digit house price growth hasn't been seen for over a decade.

You can certainly argue that the planning system is flawed (it is) and you can certainly argue that there are not enough houses in certain areas and too many in others, and that the quality overall is poor.

And you can certainly argue that there's really no need for British homes to be the smallest in Europe. Yes we have a relatively big population but we're not jammed in that tightly.

But a blanket policy of just "building more" won't help. House prices are high because the cost of borrowing is low.

Put very simply, here's how it works. At interest rates of 10%, a £900 monthly payment will pay for a 25-year repayment mortgage of £100,000. At interest rates of 2%, £900 a month will buy you a 25-year repayment mortgage of just over £210,000.

That's why house prices go up when interest rates go down (assuming credit conditions slacken at roughly the same pace). Because the amount you can borrow to pay for the same house goes up.

It's that straightforward. Physical supply and demand does have an effect of course it does but it's marginal relative to the effect of the supply of credit.

So here's the good news. Interest rates can barely go much lower, and rules around mortgage lending are tighter than they once were (there are still signs of lenders getting more excitable again but we're not back in Northern Rock territory yet).

Meanwhile, wages are rising. So overall, rising wages should improve affordability while stable interest rates keep a lid on house price growth.

So we make some headway into the frustration caused by unaffordable homes, while buying ourselves time to take a more considered view and put in place deeper reforms that might put an end to the perpetual cycle of boom and bust.

OK, if I'm honest, I'm not optimistic about that last point it would require too much long-term thinking. But having a bit of a breather at least from house price woes would be healthy for us all.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Are UK house prices set to fall? It’s not so simple

Are UK house prices set to fall? It’s not so simpleAnalysis Figures suggest UK house prices are starting to slide, but we shouldn’t take these numbers at face value, explains Rupert Hargreaves.

-

Tesco looks well-placed to ride out the cost of living crisis – investors take note

Tesco looks well-placed to ride out the cost of living crisis – investors take noteAnalysis Surging inflation is bad news for retailers. But supermarket giant Tesco looks better placed to cope than most, says Rupert Hargreaves.

-

It may not look like it, but the UK housing market is cooling off

It may not look like it, but the UK housing market is cooling offAnalysis Recent house price statistics show UK house prices rising. But John Stepek explains why the market is in fact slowing down and what this means for you.

-

Think the oil price is high now? You ain’t seen nothing yet

Think the oil price is high now? You ain’t seen nothing yetAnalysis The oil price has been on a tear in recent months. Dominic Frisby explains why oil in fact is still very cheap relative to other assets.

-

What can markets tell us about the economy and geopolitics?

What can markets tell us about the economy and geopolitics?Sponsored Markets have remained resilient despite Russia's war with Ukraine. Max King rounds up how reliable the stockmarket is in predicting economic outlooks.

-

The tech bubble has burst – but I still want a Peloton

The tech bubble has burst – but I still want a PelotonAnalysis Peloton was one of the big winners from the Covid tech boom. But it's fallen over 90% as the tech stock bubble bursts and and everything else falls in tandem. Here, Dominic Frisby explains where to hide as markets crash.

-

The market is adjusting to a new “short dreams, long reality” world

The market is adjusting to a new “short dreams, long reality” worldAnalysis As interest rates rise, things are starting to change, says John Stepek. Reality is biting back. Gone are the fanciful ideas built on hope – a business now needs a solid foundation.

-

Are UK house prices heading for a fall?

Are UK house prices heading for a fall?Analysis UK house-price growth is slowing as interest rates rise. But interest rates aren’t all that matters for house prices, says John Stepek.