Running out of human workers? Better buy robots

Record high employment means that businesses are turning to automation – Merryn Somerset Webb asks Walter Price of the Allianz Technology Trust about the best ways to invest.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Horrible news for British strawberry lovers, says The Guardian: this year's crop which has started to ripen two weeks early, thanks to the good spring weather may end up rotting on the ground. Why? A shortage of fruit-pickers. Growers across Europe are "competing for labour". Demand is high everywhere (hence better deals on pay, bonuses and accommodation), but supply is falling fast: wages in Romania (where most EU fruit-pickers come from) have risen such that workers no longer make six times the local rate abroad, but more like three-and-a-half times. That rather changes the incentive and the supply of strawberries.

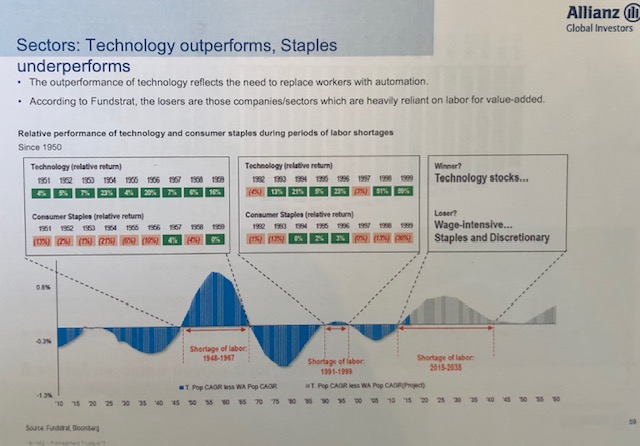

Or so the story goes. But if the worriers were to look a little deeper into it, they might find that the picking panic is overdone. Enter Fieldwork Robotics, a spinout from the University of Plymouth, that has developed a fruit-picking robot (a "mechanical arm and hand that runs on wheels", says The Times), which will apparently be able to pick 25,000 berries a day. Exciting stuff. But no surprise, I suspect, to Walter Price, manager of Allianz Technology Trust (LSE: ATT). Nothing, he says, drives spending on new technology more than a shortage of labour. Between 1948 and 1967, tech spending leapt from around 0.5% of US GDP to 1.5%. Between 1991 and 1999, it went from 2.9% to 4.7%. Now, as another shortage begins, it is rising again. It is currently at around 3.5%, says Price, and is forecast (by Fundstrat) to rise to 5.5% by 2050 as firms rush to invest in labour-replacing automation (Fundstrat suggests the US will see a shortfall of 8.2 million workers over the next decade alone).

Follow this logic and it makes sense that tech stocks should outperform in periods of labour shortage (as everyone rushes to buy their products), while firms that are "heavily reliant on labour to add value" lose out. Conveniently, that is exactly what the data shows. When we met last week, Price produced a series of charts showing that in past periods of labour shortage, tech stocks trounced consumer staples (see example below).

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The same is true of the (so far short) period since the labour market started tightening in the US in 2015. If the past repeats, tech stocks should outperform for another couple of decades at least.

Which tech stocks will do best?

This hypothesis fits neatly with many of the themes we have been discussing in MoneyWeek for years. We have, for example, argued that cheap and tax credit-subsidised labour lies at the heart of our productivity problem: after all, if workers are so cheap that you can hire as many as you like without denting your margins, why invest in new technology that (in the short term) will? Quite. So what kind of tech stocks does Price have in mind? Right now, mostly mid-caps that can exploit areas of "innovative disruption". He particularly likes cloud computing. We are, he says, at an "inflection point" where cost-sensitive firms and governments are favouring the cloud and "software as a service" over one-off product purchases.

Robotics and automation also feature heavily in his 50-70 stock portfolio, for the demographic reasons mentioned above, as well as a drive by Western governments to regain traction in manufacturing, and to remain competitive with emerging markets: Price and I agree that one effect of Donald Trump's tariffs will be accelerated reshoring, for example. One stock to watch is Teradyne (Nasdaq: TER), says Price it is valued as though it were just an automatic test-equipment maker, but it also makes robots for the defence industry as well as for warehousing and manufacturing, and should be valued as such.

Tech stocks less expensive than they look?

So what of prices? We've written many times that we aren't convinced the tech sector can hold at today's prices, and the forward price/earnings (p/e) ratio of the trust of more than 30 times won't look reasonable to anyone who judges value by p/e (see my interview with Lyrical Asset Management's Andrew Wellington from three weeks ago). But Price thinks they aren't unreasonable. Comparisons with the tech bubble of the late 1990s are silly, he says. Back then valuations were unsupported by earnings, cash flows, and the ability of firms to return those cash flows to investors. That's not the case now: in this cycle, growth is supported by real earnings and real cash. In a low-growth world, it's one of the few areas that is generating real growth by creating new markets and significantly changing old ones (the car market is being transformed by tech, for example).

The fund has a good record of outperformance (up 550% since 2007, beating the index by 180%); isn't too expensive (although it does have a performance fee attached to it); and is run in the kind of high-conviction way we approve of (the active share is around 85%, so it is far from being a closet index tracker). If you want to be in the US tech sector (84% of the portfolio), but can't quite cope with too much of the FANGS, it is worth a look.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change looms

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change loomsChanges to inheritance tax (IHT) rules for unused pension pots from April 2027 could trigger an ‘exodus of large defined contribution pension pots’, as retirees spend their savings rather than leave their loved ones with an IHT bill.

-

Why do experts think emerging markets will outperform?

Why do experts think emerging markets will outperform?Emerging markets were one of the top-performing themes of 2025, but they could have further to run as global investors diversify

-

House prices to crash? Your house may still be making you money, but not for much longer

House prices to crash? Your house may still be making you money, but not for much longerOpinion If you’re relying on your property to fund your pension, you may have to think again. But, says Merryn Somerset Webb, if house prices start to fall there may be a silver lining.

-

Prepare your portfolio for recession

Prepare your portfolio for recessionOpinion A recession is looking increasingly likely. Add in a bear market and soaring inflation, and things are going to get very complicated for investors, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Investing for income? Here are six investment trusts to buy now

Investing for income? Here are six investment trusts to buy nowOpinion For many savers and investors, income is getting hard to find. But it's not impossible to find, says Merryn Somerset Webb. Here, she picks six investment trusts that are currently yielding more than 4%.

-

Stories are great – but investors should stick to reality

Stories are great – but investors should stick to realityOpinion Everybody loves a story – and investors are no exception. But it’s easy to get carried away, says Merryn Somerset Webb, and forget the underlying truth of the market.

-

Everything is collapsing at once – here’s what to do about it

Everything is collapsing at once – here’s what to do about itOpinion Equity and bond markets are crashing, while inflation destroys the value of cash. Merryn Somerset Webb looks at where investors can turn to protect their wealth.

-

ESG investing could end up being a classic mistake

ESG investing could end up being a classic mistakeOpinion ESG investing has been embraced with enormous speed and zeal. But think long and hard before buying in, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

UK house prices will fall – but not for a few years

UK house prices will fall – but not for a few yearsOpinion UK house prices look out of reach for many. But the truth is that British property is surprisingly affordable, says Merryn Somerset Webb. Prices will fall at some point – but not yet.

-

This isn’t the stagflationary 1970s – but neither is it the low-rate world of the 2010s

This isn’t the stagflationary 1970s – but neither is it the low-rate world of the 2010sOpinion With soaring energy prices and high inflation, it might seem like we’re on a fast track back to the 1970s. We’re not, says Merryn Somerset Webb. But we’re not going back to the 2010s either.