It’s time to reshape our beleaguered housing market

From Help to Buy to stamp-duty charges, housing has seen unprecedented government interference in recent years. What’s our experts’ take on the outcome? John Stepek chairs our Roundtable discussion.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Our Roundtable panel

Robin Hardystockbroking analyst, Shore Capital

Ed Meadfounder, Viewber; non-executive director, Douglas & Gordon

Naomi HeatonCEO and founder, London Central Portfolio

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Henry Pryorindependent buying agent

James Wyattdirector, Parthenia Valuation

John Stepek: On house prices, MoneyWeek's ideal scenario is that wages go up, house prices stay flat, affordability improves, and everyone's happy. What are the odds, James?

James Wyatt: I'd say 20%-30%. The powers that be want to engineer this "soft-growth" scenario, and will do everything they can to support the housing market, because if they don't, the banks will be in even more trouble than they have been. And ultimately, there is a shortage of house building, and interest rates are likely to remain low for a long time. But looking even a year or two ahead is fraught with difficulties. There are just too many potential trouble spots whether Europe, Donald Trump in America, or something else that could undermine confidence. And the property market is driven by confidence.

Ed Mead: I look at things from a London perspective, and I actually think this is the best time to buy in London for donkey's years. Firstly, if people have to sell in central London, they will sell for well below asking price. Secondly, the best time to upgrade is when the market is falling. If you're struggling to sell your relatively normal for London £1m house, then you'll take £850,000 for it. But if you're looking at a £2.5m house, you might be able to buy it for £2m. Who's the winner there? People think, "house prices are falling, what a disaster". But it's great for buyers.

James: We work with Property Vision, and since 2014 house prices in London are down around 20%, and flats 14%. So factor in inflation and you're looking at a fall in prime central London of near-30% on houses and 25% on flats. So London is adjusting a lot faster than people realise.

Ed: And if you look outside London and the southeast, prices are still pretty much where they were ten or 12 years ago, in nominal terms. So we have to be some way down the road to that soft landing already but that might be a little bit optimistic.

Naomi Heaton: The fall in London prices has been partly Brexit-related, but I think that tax has beenthe greatest issue. Those changes have now been absorbed and prices in central London are probably somewhere near the bottom. But I feel that the rest of the country is going to be much more affected by a loss of consumer confidence. People are genuinely concerned about Brexit and how it might affect their jobs. Transactions are falling everywhere and people aren't going to try to trade up because they don't like selling their houses for less than their next-door neighbour did two years ago. So I expect real stagnation in that market.

Henry Pryor: I think it'll be even worse than that.The next 12 months are going to be painful.

John: Why the next 12 months?

Henry: Because who will be brave enough tomake what, for most people, is their biggest single purchase, in the fourth quarter of this year, or first quarter of next, ahead of Brexit day on 29 Marchnext year?

John: Do you think Brexit is that significant tomost people?

Henry: Maybe not, but why risk it, giventhat they don't have to commit beforethen? Some people will be forced to sell during the six months before Brexit, but very few people will be forced to buy.So the only deals that will go through will be those where buyers feel they've got a sufficient discount to take the gamble on committing before 29 March. Otherwise they'll just wait until June.

It'll be like the millennium bug. On New Year's Eve 1999, people were asking: "Will my computer keep working? Will aeroplanes fall out of the sky?" It turns out that it was fine. And I've got no particular reason to think Brexit will be any worse I'm sure it will somehow be managed but human nature being what it is, people will just put it off.

So the house-price indices published in June and July next year will reflect the deals that weren't done, or the very few that were done, in the run-up to Brexit. And most of those will be at a discount. Therefore I think that in 12 months' time, house prices, as far as the indices ignoring Rightmove, which is asking prices go, will generally be at least 5% lower.

The rising cost of buying a house

John: Hasn't the cost of buying gone up over the past five years due to tax changes? Isn't that more significant than Brexit?

Ed: The cost of buying has certainly had an impact in London, particularly on the buy-to-let market. The government's been involved in a social-engineering exercise for the last five years, putting up tax, trying to stop people from overseas buying, non-natural person taxes, ATEDs [an annual levy on homes bought using companies] that really has changed the cost of buying and that's where transactions are crashing.

Robin Hardy: Yes, but overall the cost of buying nationwide has barely changed since 2011. We track a thing called the "invisible house-price index" you take the average customer, buying the average house in the UK, at the average mortgage rate. It turns out that payments have been virtually flat for several years now. So it hasn't cost the man in the street any more to buy a house, regardless of how much the actual price has gone up.

But this is now coming to an end. You've had house prices rising and interest rates falling for ten years. Now, for the first time in a decade, you've got mortgage rates going up and most likely they will rise faster than most people appreciate. So for a long time now it has cost roughly £911 a month to fund a mortgage for the average house. But that is starting to tick up, and you're going to see that eating away at people's desire to buy a house.

John: You said that mortgage rates are going to go up faster than people expect. Why?

Robin: Because it isn't about base rates but swap rates, the wholesale cost of funds for lenders. In June 2017 lenders could borrow cheaply from the Bank of England's funding for lending scheme. Now it's ended the wholesale funding cost for a lender has gone up.

Henry: And house prices are predicated on the cost and availability of credit, which is one reason why the downward pressure is going to continue.

Ed: Yes, but it's still quite cheap compared withlong-term historical lending, isn't it?

Robin: It is, but while it's a lot cheaper to borrow than it was in the early Noughties, you also have to borrow a lot more. I bought a new house in 2000 at £60,000 it's now worth £225,000.

Ed: And what have wages done over that period?

Robin: They've gone up about 11% since 2007.

James: The market is certainly overvalued the Economist compares house prices to income and to rents, and the UK market is 30% overvalued against income and 45% against rents. But how is it going to get to fair value? This goes back to the original question. The government is trying to engineer a slow, steady decline in real prices, because it can't risk the knock-on effect that a crash would have on banks and building societies. That's why we've got negative real interest rates and we're likely to have for some time.

The Help to Buy disaster

Naomi: I'm not sure they'll be able to do that. My feeling is that prices will fall nationally and we will start seeing people in negative equity. In particular, the Help to Buy scheme enabling people toborrow at 95% loan to value is remarkably foolish.Many of these buyers will find themselves in negative equity and unable to refinance at competitive rates. Help to Buy has helped builders to sustain their sales, but I think it's highly irresponsible.

Henry: Yes, we should stop it.

James: The government's got another problem a lot of people who've bought via Help to Buy have bought leasehold houses. They have found that some of these have very nasty, onerous leases, with ground rents doubling every ten years. And their solicitors didn't raise it during the buying process because the solicitors were recommended by the developers.

Ed: Well I hope those solicitors have very good professional indemnity insurance.

James: Yes, well we'll find out. The thing is, leases with onerous clauses have existed for some time, but it's coming to a head now because the government, through Help to Buy, has been financing this huge leasehold scam.

John: Why have so many of these houses been built with leaseholds anyway?

Ed: It basically gives the developers another revenue stream they can sell the ground rents on, and it gives them another slug of money to fund their next development.

Robin: And, to be fair to the house builders,they didn't imagine that risk-free interest rateswould drop to almost zero, and that as a resultthe value of these ground rents now an assetclass in and of themselves would rise sosignificantly.

James: Yes, this is the underlying issue. The cheapness of money has effectively compressed yields, and pushed up the value of ground-rent portfolios.

John: Because investors will pay handsomely for any asset that offers a half-decent yield?

Robin: Yes, they deliberately made an asset class out of it. I bought a flat in 1989 and the ground rent was around £30 a year to be reviewed every 33 years. But today ground rents are £400 to £600 from the start, and it also now seems to be acceptable for them to be indexed to inflation. So it's gone from being a purely functional arrangement with virtually no value, designed mainly to help with the upkeep of communal areas, to being an asset class in itself.

Ed: And thank goodness the developers have been caught out on it.

Naomi: But the other issue with Help to Buy is that those who use it have to buy new-builds. These tend to sell at about a 20% premium to old houses, but that premium doesn't last. So these buyers are also being forced into a category of purchase that is actually less economic than if they were buying older properties.

James: The government has said that it's going to do something about it, what with all the press coverage. The problem is that if it actually changes the law, freeholders will demand compensation.

Henry: Yes, who's going to bail out the freeholders?

Ed: But the vast majority of leaseholds work absolutely fine. You've got a small percentage in London, and you've got these new people taking the mickey.They should sort out the ones that are onerous. But most leaseholds have worked perfectly well for hundreds of years. Sure, you can introduce a new system that has to be used from now on. But don't complain that everything that's gone before is sullied, because it's not.

Are there opportunities, or just threats?

John: If you did decide to buy a property anywhere in the UK right now, is there anywhere that you would describe as a hot spot?

Naomi: Central London always rebounds more quickly than the rest of the country, and I think that we are seeing prices tracking along the bottom at the moment. The only people who are selling are distressed sellers. So valuations are dependent on those who have to sell at a discount. So,I do think that we're probably at the bottom of the curve there.

Ed: Also, if you look back to the financial crisis, the reason for the V-shaped recovery in London was currency-based, not anything to do with interest rates. It was because the pound slid in value and foreigners thought, "yes, please, I'll have some of that". Well, what's going to happen after Brexit? Everyone's saying the same thing the currency is going to fall.

John: But the pound has already fallen a lot. Unless Brexit is far worse than anyone expects, sterling has fallen as far as it's going to, more than likely.

Ed: But I think a lot of people are ready to buy the minute they know what colour of Brexit we're getting. London hasn't suddenly lost its appeal. It's still in the Greenwich meridian, it's still economically and politically stable.

John: Henry, is there anywhere that you would consider is an opportunity?

Henry: I still think that the threats to anybody wishing to buy can't and shouldn't be underestimated. Politics and social inequality are the two biggest threats to the housing market. All three of the main political parties have now publicly identified wealth as where they're going to get their tax revenue, rather than income.

What's the most obvious example of anyone's wealth? A house. They can't take it away to the Isle of Man or the Caribbean. So the government can serve the notice, and if the bill's not paid, they take it.All three main political parties if you still include the Liberal Democrats have said we'll have a land value tax, or potentially scrap the capital gains tax [CGT] exemption on the principal residence. So in the conversations I have with clients who want to buy, my first question ironically is "are you sure?"

Look out for wealth taxes

John: So you see a land value tax being introduced?

Henry: Yes.

James: It's about time.

John: When do you think it'll happen?

Henry: In the next five years. Scrap stamp duty, scrap council tax. Most people will feel better off and as a result will vote for it.

James: Yes, just a land value tax is the fairest way of doing it.

John: What form do you think it will take?

James: Everything's in place for it now. It's very easy for the Land Registry to work out what the underlying value of the land is.

Henry: From an investment perspective, farm land is unlikely to be in the vanguard, although it'll catch up. But other property commercial property and residential property certainly is. I mean, it's been openly discussed in Westminster. And the CGT exemption for principal residence is indefensible.

John: Sure, but do you want to be the chancellor who scraps it?

Henry: But who is going to stand up on BBC News or the Today programme and say: "No, that's a very bad idea"? You'd have to be a really brave politician.

James: Someone will say: "Look, the NHS needs more money; we are running a budget deficit; our national debt is £1.7trn" and they'll say we have to take action, let's scrap the CGT exemption.

Robin: I don't think they'll do that, because you'd hole the market below the waterline. If you want to move, you need the money from the capital gains you've made on your existing house.

Naomi: Yes, and we need people to move up so that other people can get on the ladder. We have a massive affordable housing crisis. Even if they build a million new houses over the next five years, we'll be no better off than we are now because of the growth in household numbers. And it seems to me that the best way to reduce prices is to have more supply.

Robin: If you want to get to building 300,000 houses a year in a way that works without hugely upsetting the capital values for existing vendors, destabilising banks, and making everybody feel less confident it's got to be through different tenure. It's got to be through build-to-rent.

Henry: I completely agree. It's not how much we're building, it's what we're building.

A highly politicised market

John: We've spent a lot of time tonight talking about how the housing market needs to be reshaped so that everyone has a fair crack at it, which is not how this discussion has gone in the past. Would you say that politics is now much more significant than in the past?

Ed: Yes, there's been unprecedented interference in the property market: Help to Buy, stamp duty changes...

James: And how many housing ministers have we had in recent years?

Henry: 18 since 2000.

Ed: It's one of the main things in the UK that needs a long-term answer and gets anything but. It needs to be taken out of the hands of politicians.

James: We do need to improve tenure we need longer tenancies so that people feel secure renting for long periods. Leasehold needs to be reformed, and commonhold needs to be reinvigorated. These things the government can do quite easily, and the Law Commission is reporting back soon on that. We also need to reform the planning system and get rid of stamp duty because we all know that if you raise the cost of transactions, you're going to have fewer transactions. So get rid of stamp duty and bring in land-value tax the capability is easily there. So there are lots of things the government can and should do and it's starting to do it. I'm cautiously optimistic.

John: And do you think the government is misguided to try and encourage home ownership at all? Obviously Help to Buy is a stupid idea.

Robin: It has an obsession with trying to get home ownership back to 70%, which is the core of the problem. My daughter went on a German exchange visit several years ago. The family she went to stay with lived in a beautifully built, well-maintained apartment owned by an insurer in Frankfurt. They'd lived there for seven years and intended to stay there for another six while their children were at school.The parents were in their mid-40s and had no interest in home ownership because it just didn't make any sense for them. They were happy where they were, and they would follow a typical German pattern and wait until around the age of 50 or whatever to buy a house. They had no interest at that stage of their family life.

Ed: That's because there's not really any house price inflation, so there's no benefit to owning because the value's not going to go up.

What's next for house prices?

John: This all sounds good, but you have to get this past voters. Do you think there's a critical mass who will back policies such as a wealth or land-value tax?

Robin: Where will the impact of such a change be greatest? London. Where is the strongest Labour and LibDem representation? London. So the people who will be most affected don't seem that bothered unless they're just not seeing the risk of voting for the parties that are most likely to introduce these changes.

John: Good point. One final question: what are your forecasts for house prices in the next one to five years?

James: Nationally house prices in the next year will go up by about 2% in nominal terms. In five years' time I think it'll probably be up 8%-10% nominal, but down probably 5% or more in real terms .

Ed: I'm going to say up 5% next year nominal and 20% over five years for the UK as a whole.

Robin: I'd say that we're looking at next year 0%,five years up 6.75%.

Henry: I think it'll be down 5% in a year, down 8% in five years nominal.

Naomi: Nationally, down in a year by at least 2%. Over five-years, prices may be back to about where they will be next year. So maybe down and then starting to curve back up.

John: Thanks everyone.

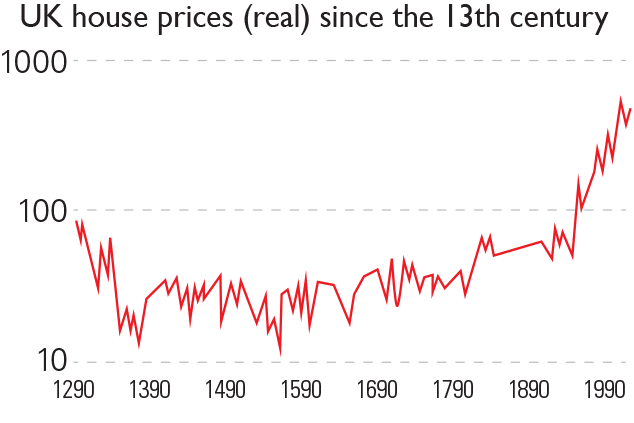

How house prices have changed since 1290

If you look at house prices over the long run, you'll find that in many countries bar the odd boom and bust the average house value tracks inflation over the very long run. In other words, in "real" terms (that is, after inflation), you don't make much money from buying and holding "bricks and mortar". However, the UK at least since the latter half of the 20th century has been very much an exception to this rule.

As the latest Deutsche Bank Long-Term Asset Return Study yearbook points out, between 1290 and 1939 the average UK house price actually fell by nearly 50% in "real" terms. However, in the 79 years since then, real house prices have grown at an annual rate of 3%. The result of that can be seen in the chart below.

What's driven this rampant price inflation? While UK house prices might stick out somewhat amid global property markets, as Jim Reid of Deutsche Bank notes, they are by no means the only assets to have seen extraordinary inflation the period between 1950 and 2000 "is like no other in human or financial history in terms of population growth, economic growth, inflation or asset prices". For example, consumer prices in the UK were also broadly stable between 1800 and 1938, but since then, prices have risen 50-fold.

Broadly speaking, Reid and his team argue that the big change in the 20th century was the boom in population combined with the shift to an entirely fiat monetary system (one where money is backed by nothing more than government authority, rather than precious metals or any other commodity). Deflation, an integral aspect of a "hard" money system such as the gold standard, became politically untenable in a fast-growing global economy with ever-growing demand for higher public spending by governments.

As a result, following World War II, the Bretton Woods monetary system (which tied global currencies to gold via the dollar) was put under increasing strain until it collapsed in 1971, when the US uncoupled the dollar from gold. Since then, notes the Deutsche team, no country (of 87 studied) has seen average annual inflation of below 2%. In other words, we've lived through an inflationary era like no other.

"Perhaps UKhousing is the ultimate population-sensitive asset," Reid speculates. "As a small island with heavy control on new homebuilding, high population growth but limited extra housing supply has put massive upward pressure on prices over the last several decades".

We're not convincedthat lack of supply is the biggest factor we're more inclined to give more weight to loose monetary policy but the chart does give some indication of why housing has become such a big political issue.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Invest in space: the final frontier for investors

Invest in space: the final frontier for investorsCover Story Matthew Partridge takes a look at how to invest in space, and explores the top stocks to buy to build exposure to this rapidly expanding sector.

-

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growth

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growthCover Story It’s time to invest in Brazil as the economic powerhouse looks set to profit from the two key trends of the next 20 years: the global energy transition and population growth, says James McKeigue.

-

5 of the world’s best stocks

5 of the world’s best stocksCover Story Here are five of the world’s best stocks according to Rupert Hargreaves. He believes all of these businesses have unique advantages that will help them grow.

-

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sector

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sectorCover Story Move over, Silicon Valley. Over the past two decades the UK has become one of the main global hubs for tech start-ups. Matthew Partridge explains why, and highlights the most promising investments.

-

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?Cover Story Gold has always been the most reliable form of money. Now collaboration between China and Russia could lead to a new gold-backed means of exchange – giving prices a big boost, says Dominic Frisby

-

How to invest in videogames – a Great British success story

How to invest in videogames – a Great British success storyCover Story The pandemic gave the videogame sector a big boost, and that strong growth will endure. Bruce Packard provides an overview of the global outlook and assesses the four key UK-listed gaming firms.

-

How to invest in smart factories as the “fourth industrial revolution” arrives

How to invest in smart factories as the “fourth industrial revolution” arrivesCover Story Exciting new technologies and trends are coming together to change the face of manufacturing. Matthew Partridge looks at the companies that will drive the fourth industrial revolution.

-

Why now is a good time to buy diamond miners

Why now is a good time to buy diamond minersCover Story Demand for the gems is set to outstrip supply, making it a good time to buy miners, says David J. Stevenson.