Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

There's a general consensus among investors that disruptive and aggressive digital giants are eating the lunch of traditional media, and that it's all over bar the shouting for the old-school advertising agencies. There's a lot of truth to this perception. Online firms have devoured advertising money previously earmarked for television, print and radio. This has in turn put the business models of big advertising agencies themselves under severe pressure.

Globally, 36.8% of all money spent on advertising will go to digital this year, reckons media investment firm GroupM. In some key markets, such as the UK, China and France, the proportion is far greater than that more money is now spent on digital in those markets than on any other advertising medium. Moreover, most of this money is going to just two companies, Facebook and Google, which between them accounted for 84% of all global digital ad spend in 2017 (excluding China).

Yet, despite the relentless growth of digital advertising, some media analysts and industry executives are starting to wonder if concerns about traditional media might be overplayed, and if the Armageddon scenario might be a little overdone. They are also questioning whether the tech giants can continue to gobble up advertising revenue as rapidly as they have in recent years, amid growing doubts over the effectiveness of digital advertising. The pendulum has swung too far towards the digital firms, says Ian Whittaker, head of European media research at investment bank Liberum, who is positive on traditional media companies such as ITV and agencies such as WPP and Publicis. Meanwhile, Morag Blazey, the chief executive of market intelligence at independent marketing and media consultancy Ebiquity, believes advertisers will soon start to rebalance their campaigns to manage online and offline media more effectively.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The revenge of traditional media

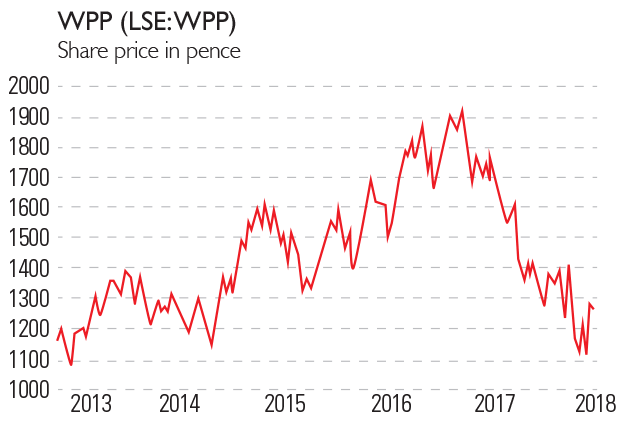

At first glance, the idea that traditional media might come back into fashion seems outlandish. The growth of the digital giants seems to be continuing unchecked. Despite recent scandals over data privacy, Facebook posted strong first-quarter results, as did Google parent Alphabet. The share prices of both companies have returned close to the record highs they hit earlier in the year. By contrast, advertising group WPP has endured a torrid year, culminating in the exit of chief executive Sir Martin Sorrell. His departure led to claims that the writing is on the wall for the traditional advertising agency, with big clients such as consumer-goods giant Procter & Gamble cutting their marketing budgets and taking more work in-house, and internet companies now controlling the bulk of digital advertising.

Broadcaster ITV's share price, meanwhile, has dropped by almost 30% in the past 12 months. The UK's biggest commercial broadcaster said advertising revenues fell by 5% to £1.6bn in 2017. ITV is also fighting off competition for viewers from digital rivals such as Netflix and Amazon Prime. And other media firms have also been affected the hardest hit have been newspaper and publishing companies that have experienced sharp falls in revenues as advertisers and readers move to online platforms (such as Google and Facebook). For example, the share price of Johnston Press, which publishes titles including the i, The Yorkshire Post and The Scotsman, has fallen by nearly 40% year on year.

However, there is "no uniform picture of panic across established media", says Matti Littunen, senior analyst at media research firm Enders Analysis. "In fact, there are a number of positive stories as well." TV advertising, for example, has proved remarkably robust. While TV advertising revenue fell in 2017, that followed seven consecutive years of growth in the UK. And some TV executives argue that last year's decline was caused more by political and economic uncertainty about Britain's plans to leave the EU than by digital disruption.

And while the growth of digital streaming companies such as Netflix and Amazon Prime is affecting the TV market, these don't carry advertising so they are competitors for an audience's time and attention, but not for advertising spend. At the same time, traditional TV companies are investing heavily in their own catch-up services, such as ITV Hub and All4, where adverts are played in full during programmes. TV executives acknowledge that younger viewers are watching less television, favouring YouTube and other online videos instead but argue that millennials start watching a lot more TV as they age and have children.

The ad outlook is not as bleak as you might think

Prospects for TV advertising in 2018 are looking more promising than last year, partly because it is World Cup year, but also because advertisers realise that some shows are still capable of delivering large audiences at a time when audiences are otherwise highly fragmented across digital platforms. For example, long-running soap Coronation Street still averages 7.6 million viewers an episode, while reality TV stalwart I'm A Celebrity Get Me Out of Here launched with 12.69 million in 2017. As a result, "TV remains a mass market medium" like no other, says Liberum's Ian Whittaker. For similar reasons, many marketers also see virtue in the oldest form of advertising media out-of-home (or what used to be known as poster ads). This sort of advertising is also much more versatile now, thanks to digital signage. Indeed, apart from digital, it is the only advertising medium that is actually growing its share of the market up from 6.1% in 2016 to 6.2% in 2017, according to GroupM. Radio is just about clinging onto its market share, too.

Whittaker also thinks that concerns about the big advertising companies have been overdone. The single most important part of the agency groups' businesses is media buying, he says it accounts for just under half the profits at Publicis and WPP. The big worry for agencies is that media buying is also the business that is most liable to be taken in-house by clients, or taken over by management consultancies such as Accenture and Deloitte, who are increasingly encroaching on the advertising world's turf by building their own digital marketing services.

However, says Whittaker, agency media business still seems to be doing well, according to recent results. "There may be a little bit of a slowdown, but it is not a business in decline." Yet that might not be the impression the market is currently giving WPP in particular is now trading at a significant discount to its global peers, including Publicis, Omnicom and Interpublic. "Given the agencies are rather a homogenous bunch, and WPP's performance is not materially different from the others, this underperformance/under-rating seems unjustified." Others point out that ad agencies have not lost out to digital platforms as badly as people think. Google and Facebook generate a great deal of their advertising income from small and medium-sized businesses "the kind of companies that ad agencies have never been able to service effectively", as Enders' Matti Littunen puts it.

The backlash against the disrupters

Meanwhile, there are signs of a growing backlash against digital media. Increasingly, concerns are being aired about a wide range of issues: how many people really watch digital ads? How is consumer data being used or misused, and what regulatory risks might be involved? And the issue of brand safety the running of campaigns alongside inappropriate content has really come to the fore for advertisers, with several high-profile stories of big-name brands pulling their adverts from various platforms because they have appeared alongside content that is seen to be toxic to their brands.

Marc Pritchard, Procter & Gamble's chief brand officer, last year described the digital media supply chain as "murky at best and fraudulent at worst". Ebiquity recently carried out a major piece of research into the advertising market, based on interviews with more than 100 advertisers and agencies. The "Re-evaluating Media" report found that most senior advertisers, marketers and agency executives think online and social media are the best platforms to use for brand-building. However, there is simply no evidence to back up those perceptions, says Ebiquity's Blazey. Instead, the research rates TV as best for brand-building, followed by newspapers, magazines and radio in equal second place. One telecoms advertiser is quoted in the report as saying: "If you want to hit a ton of people in a creative way and get your message across, there's really no better way than TV. It's expensive, but it does the job."

It turns out that contrary to the views of many executives the two least-effective media for brand building are online display and paid-for social media, according to Ebiquity's research. In short, "offline media still has a huge role to play in delivering what advertisers need to build their brand. Online media struggles in many of these deliverables," says Blazey. Ebiquity also notes that TV advertising gives the best return on investment, with a £1.73 return for every pound spent. For radio it is £1.61 and print £1.44. Online video lags at just £1.21 while the return for online display is 82p so advertisers are losing 18p in every pound they spend. This chimes with the reality of most people who, if asked, will tell you that online video advertising is incredibly annoying.

That is, of course, if anyone is taking notice of it. It is hard to know for sure, as digital measurement standards are so poor. For example, digital companies will record a video as having been viewed if just 50% of the content plays for two consecutive seconds, with the sound off probably not the sort of exposure their clients would hope to be paying for. Then there was the famous claim in ad-land a few years ago that you are more likely to survive a plane crash than click on an online banner ad which sounds unlikely, but then again, when was the last time you clicked on a banner?

Despite this, online advertising remains highly fashionable in the world of marketing partly because there is a belief that it is highly effective at targeting the right audiences. There is some truth to that, but targeting can be taken too far, says Blazey, who tells how last year she ordered a new shed online for her mother-in-law. For months after she was targeted across the internet by ads selling sheds. "How many sheds does a girl need?"

There is also very little research to prove that online advertising works, largely because of a lack of transparency at digital firms. This may change. Last month, the Chief Marketing Officer Council said that marketing leaders globally "will no longer tolerate deficient advertising measurement" from digital platforms. It reported that 21% of marketers have cut their spending on advertising because of recent news coverage about inaccurate, questionable and false digital media reporting.

How traditional media is striking back

Enders' Littunen argues that with all this going on, the TV, radio and out-of-home sectors still have time to figure out how to keep their services relevant in the face of the digital onslaught. One example of how the traditional players are adapting is Sky's new AdSmart service, which launched last month after a six-month trial.

Borrowing some of the targeting attributes of digital media, AdSmart tailors what is shown in TV ad breaks according to a household's profile and location. Sky hopes that AdSmart will attract new brands to advertising on TV, including local businesses that may have previously concluded that TV advertising wasn't the right medium for their purposes. Rival Virgin Media has also signed up to AdSmart.

It might not be the killer app that allows TV to halt digital's growth in its tracks, but it's proof that established media can also innovate and remain relevant to advertisers.

And it's yet another reason why investors should be rethinking their approach to media companies contrary to the hype around digital, the more traditional media players are still very much a live force in advertising.

Media players worth watching

WPP (LSE: WPP) has significantly underperformed its advertising-agency peers in share-price terms since the start of the year. Investment bank Liberum thinks the gap could start to close as investors price up a potential sale of some assets following the departure last month of chief executive Sir Martin Sorrell, who was arguably the glue that held much of WPP together.

Another agency group to consider is Publicis (Paris: PUB), the world's third-largest advertising agency by revenues. The company recently unveiled a major strategic plan for the next three years, earmarking up to €1.5bn for acquisitions, €450m in cost savings and adding thousands of people to its technology-execution centres by 2020. Despite pressures on all agency groups over the past year, its shares have held up better than those of rivals such as Omnicom and WPP.

ITV (LSE: ITV) had a tough 2017, and blamed the economic and political uncertainty caused by Brexit for advertising revenue declining by 5%. Its share price has been badly knocked as a result. But there's potential for improvement this year. The broadcaster expects ad revenues to be up slightly for the first quarter of 2018, while the second quarter will benefit from the World Cup, which starts in June. Meanwhile, ITV has been working hard to make itself less reliant on the volatile ad market. Its production and distribution business ITV studios has grown significantly, producing hit shows such as Love Island and I'm A Celebrity Get Me Out of Here!

A predicted improvement for TV advertising spend in Germany in 2018, after an unexpectedly soft 2017, should benefit European entertainment company RTL Group (Euronext: RTL), which has interests in 57 TV channels and 31 radio stations. FremantleMedia, RTL Group's production arm, is a global leader in content production making shows such as the X Factor, Britain's Got Talent and The Apprentice.

Events and business information group Informa (LSE: INF) recently agreed to take over rival exhibitions operator UBM. Informa expects to make £60m a year in pre-tax cost savings, with around £50m to be delivered in 2019 more than was first expected. While digital giants such as Facebook and Google have hit the revenues of publishers, events businesses have thrived as firms look for ways to connect directly with customers.

If, on the other hand, you're still not convinced that traditional media make a good investment prospect, a good way to gain exposure to the leading digital players is via the Scottish Mortgage Investment Trust (LSE: SMT). It has surged in value in recent years after backing companies such as Amazon, its biggest holding, and China's biggest search engine, Baidu. In 2015 the trust also invested in Spotify, which soared when it debuted last month on the New York Stock Exchange.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Invest in space: the final frontier for investors

Invest in space: the final frontier for investorsCover Story Matthew Partridge takes a look at how to invest in space, and explores the top stocks to buy to build exposure to this rapidly expanding sector.

-

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growth

Invest in Brazil as the country gets set for growthCover Story It’s time to invest in Brazil as the economic powerhouse looks set to profit from the two key trends of the next 20 years: the global energy transition and population growth, says James McKeigue.

-

5 of the world’s best stocks

5 of the world’s best stocksCover Story Here are five of the world’s best stocks according to Rupert Hargreaves. He believes all of these businesses have unique advantages that will help them grow.

-

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sector

The best British tech stocks from a thriving sectorCover Story Move over, Silicon Valley. Over the past two decades the UK has become one of the main global hubs for tech start-ups. Matthew Partridge explains why, and highlights the most promising investments.

-

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?

Could gold be the basis for a new global currency?Cover Story Gold has always been the most reliable form of money. Now collaboration between China and Russia could lead to a new gold-backed means of exchange – giving prices a big boost, says Dominic Frisby

-

How to invest in videogames – a Great British success story

How to invest in videogames – a Great British success storyCover Story The pandemic gave the videogame sector a big boost, and that strong growth will endure. Bruce Packard provides an overview of the global outlook and assesses the four key UK-listed gaming firms.

-

How to invest in smart factories as the “fourth industrial revolution” arrives

How to invest in smart factories as the “fourth industrial revolution” arrivesCover Story Exciting new technologies and trends are coming together to change the face of manufacturing. Matthew Partridge looks at the companies that will drive the fourth industrial revolution.

-

Why now is a good time to buy diamond miners

Why now is a good time to buy diamond minersCover Story Demand for the gems is set to outstrip supply, making it a good time to buy miners, says David J. Stevenson.