The clowns move in: what Italy’s dysfunction means for investors

Italy’s politics have long been an international joke – but after an exceptionally farcical election at a difficult time, that joke isn't funny any more, say Frédéric Guirinec and Cris Sholto Heaton.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Italy's politics have long been an international joke but after an exceptionally farcical election at a difficult time, that joke isn't funny any more, say Frdric Guirinec and Cris Sholto Heaton.

Italy's politics have long been an international joke. For years, the country's parties seemed uniquely bad among major developed economies for their combination of buffoonery, dysfunction and flirtations with fascism, depending on who was in the ascendancy. Of course, today Donald Trump is in the White House, Britain is led by a hopeless prime minister who only keeps her job because the alternatives are even worse, and genuinely alarming far-right figures are on the rise across Europe so Italy no longer looks so exceptionally awful. But make no mistake the results of the recent elections look like yet another lurch into greater chaos.

It could take a while until we know who the country's next government will be, but there's no ambiguity about the message that the electorate is sending. The largest share of the vote went to the Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement or 5SM), with around 32% of votes cast. 5SM is an anti-establishment, eurosceptic, left-wing party founded by Beppe Grillo, a popular comedian. Grillo remains a key figure, but the party is these days technically headed by Luigi Di Maio, who would consequently lead it in government.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

However, the largest formal grouping is the combination of Forza Italia (Forward Italy),the party of billionaire former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, and the Lega Nord (Northern League), with 14% and 18% respectively. Both follow broadly right-wing policies, but share 5SM's euroscepticism (especially the more right-wing Lega).Within this grouping, the election saw a notable shift. Until recently, the Lega headed by Matteo Salvini was focused on the north of Italy (and arguing for greater autonomy sometimes even secession of the region) but it performed well nationwide in this election and relegated Forza Italia to the junior party in the group for the first time.

Finally, the ruling centre-left Partito Democratico (Democratic Party) performed poorly, winning just 19% of the vote. While a bad result was expected, this was worse than anticipated and bodes poorly for party leader Matteo Renzi and outgoing prime minister Paolo Gentiloni.

Populism is on the rise

The clear theme in these results is support for populists on both left and right of the spectrum. Both the populist parties happen to be eurosceptic, but it would be a mistake to see this result mainly as a backlash against the European Union although it could end up being a further headache for the eurozone. Instead, it's a vote against the establishment for failing to solve Italy's problems. These problems are many and it's unfair to blame the current government for most of them but that's the nature of politics and it's certainly true that Renzi and Gentiloni have not managed to introduce enough reforms to make a difference.

Italy is an important economy or at least it should be. After all, it's the third-largest economy in the eurozone after Germany and France. Unfortunately, it's been going backwards for many years: although the UK, France and Italy had economies of similar size in the early 1990s, Italy's GDP now stands at $1.9trn compared with around $2.4trn for France and the UK. GDP per capita fell behind the UK in 2013 and is now below the eurozone average at $36,200. Growth remains sluggish even as the result of the eurozone improves. The GDP growth rate picked up slightly in the fourth quarter of last year to an annualised rate of 1.5%, the highest since 2010, but that was well below the 2.5% recorded by the overall bloc.

The structural challenges that Italy faces are numerous and sizeable, and were exacerbated by the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 and the European sovereign-debt crisis that followed. Public debt now stands at 132% of GDP, the second highest in the eurozone after Greece, driven by public spending amounting to 50% of GDP. If it were not for the European Central Bank's (ECB) decision to begin buying up eurozone sovereign bonds in 2015, it is likely that the country would have been drawn into a debt crisis that had engulfed Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Cyprus by that point. While the ECB's actions warded off the problem, the fragility of Italy's banks and their bloated balance sheets full of bad loans remains a threat, not only for the country but also potentially for the stability of the euro.

A long-running problem

However, the roots of Italy's problems precede the financial crisis by many years. The labour market is extremely rigid, which has resulted in a two-tier society split between those with secure jobs and those struggling to find work. Unemployment stands at 11.7% despite reforms initiated by Renzi. Even more dramatically, youth unemployment remains above 30%, driving a significant exodus and creating a generational rift between the older generation, often syndicated and protected with secure professional positions and younger people accumulating temporary jobs. This is one of the factors driving protest votes by the young, especially those backing 5SM.

The university system in Italy is generally regarded as poor, with no universities ranked among the 100 world best. The combination of excessive bureaucracy and the need to have a solid network to make progress in employment and business has resulted in 500,000 Italians emigrating since 2008, according to official figures, and has also discouraged entrepreneurs. And corruption is disturbingly high for a major developed economy Italy ranked 54th out of 180 countries on the corruption perceptions index compiled by Transparency International, an anti-corruption campaign group.

Unequal growth fuels resentment

Economic growth is both weak and unbalanced. Growth is driven by exports (and hence by the wider global economy) rather than by domestic consumption. This almost certainly reflects a lack of pessimism about the future among Italians (one slightly positive aspect of this is that household debt stands at just 42% of GDP, compared with 58% in France and 87% in the UK). There is also a pronounced regional divide between the wealthier, industrial, exporting north and the poorer, more agricultural south, which has an unemployment rate of 29%. The region of Lombardy accounts for over a fifth of Italian GDP on its own, followed by Lazio and Veneto at around 10% each. The sixth richest regions represent two-thirds of GDP, a share that has remained roughly constant since 2000.

Resentment about the extent to which the south is perceived to have ridden on the wealth and work of northern provinces such as Lombardy and Veneto was largely responsible for driving the Lega's initial success in the region. Of course, to advance nationally the Lega needed to find a message that resonated better across the country, which Salvini succeeded in doing by blaming immigrants, asylum seekers and groups such as gypsies for many of Italy's misfortunes.

Manufacturing strength remains

In case it sounds like there is nothing going for Italy, it's worth noting that the country remains the seventh-largest manufacturer in the world, second in Europe ahead of the UK and France. Many large firms are well-regarded internationally. Carmaker Ferrari has been dubbed the world's most powerful brand, while products from major Italian fashion houses such as Gucci, Armani, Prada, Versace and Dolce & Gabbana to name but a few are emblems of conspicuous consumption everywhere. However, most exports come from mid-sized firms that are thriving despite the challenges. In particular, specialist family-owned businesses are a cornerstone of the economy not just in luxury goods, but also in industrial sectors.

Historically, Italy relied on regular depreciations in the lira to maintain the competitiveness of its exports, so being locked into the stronger euro for the past two decades has played a part in holding back the economy. (This is one of the driving forces between support for eurosceptics much of their ire is directed at the single currency rather than at the EU as a body.) However, Italian exports still stood at $455bn in 2017, making the country the eighth-largest exporter in the world. This resulted in a trade surplus of $55bn (both France and the UK run persistent deficits). Machinery represented a quarter of exports, and transportation and chemistry 10% each well ahead of the textiles, leather goods, foodstuffs and wine that are more commonly associated with the country.

In short, Italy's best-run businesses do well despite the wider economic stagnation. But it is not an easy market for foreign investors to find opportunities in even seasoned specialists have struggled. Large, blue-chip companies are in short supply, with a few exceptions, such as Fiat Chrysler and CNH Industrial in the industrial sectors, Eni and Enel in the energy sector, and financial services providers such as Assicurazioni Generali, Intesa Sanpaolo and UniCredit. Other, profitable, large and well-run businesses are often owned by wealthy Italian families or private-equity firms. The best listed firms are not cheap (see below). And it's hard to divorce the prospects for the Italian stockmarket from the wider political prospects, which remain uncertain.

Get set for horse trading

No one party or group has enough seats for a majority in either of the two houses of parliament (the Chamber of Deputies or the Senate). That means the parties must try to put together a coalition that will command enough votes to form a government. It's impossible to predict what combinations might emerge from this. In theory, one would expect 5SM to play a role in government but the party has previously said it won't go into a coalition. Whether these anti-establishment principles hold when confronted with the prospect of power is another matter. If 5SM's leaders were to change their mind, a coalition with the centre-left might be the most logical option but already the possibility of this is leading to infighting in the Democratic Party. Teaming up with Lega would bring together the two largest parties and ensure a sizeable majority but all that 5SM and Lega really have in common is some euroscepticism, calls for curbs on migration and their status as the new destination for voters who are angry with the status quo. Whether that would be enough to bring left and right together is debatable.

If no parties are able to form a government, the most obvious outcome would be a fresh election. Sergio Mattarella, the country's president, could ask parliament to support a short-term technocratic government who would not necessarily be drawn from elected politicians (as happened with the government of Mario Monti from 2011 to 2013). However, that took place under Giorgio Napolitano, the previous president, who had a reputation as a politician kingmaker it's not clear that Mattarella would be so keen to play that role. Nor is it obvious what such a government might be able to achieve in terms of reforms that could break the gridlock. In short, expect more dysfunction.

Five well-placed Italian stocks

The Milan Stock Exchange's benchmark index, the FTSE MIB, today stands at around 23,000 half the level it attained in 2007. By comparison, real GDP is still around 5.8% below the peak it reached back in 2008. Yet if you think such a poor record means that there are plenty of cheap stocks to be found, think again.

Following a triple-dip recession in 2008, 2011 and 2014 Italian banks are burdened with an estimated €165bn of non-performing loans (NPLs), mostly related to real estate and construction. The ensuing writedowns wiped out much of the capital in the Italian banking system, permanently impairing the value of a sector that accounted for a large share of the market in the pre-crisis years. Some of the worst-affected banks have been bailed out notably Monte dei Paschi di Siena, which has been through multiple increasingly farcical rescue operations over the last few years.

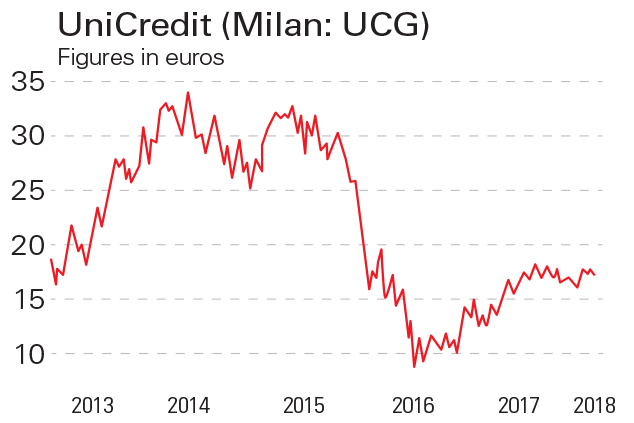

Some NPLs are being sold at a discount to investment managers, such as Fortress and Pimco, getting them off the bank's balance sheets. Reforms have also helped to speed up insolvency and enforcement proceedings. UniCredit (Milan: UCG), the largest bank, trades on a price/book ratio of 0.65. The meaningfulness of that depends on how many more NPLs you think there could be in that book value. If and it's a big if the worst is past, it might appeal to high-risk investors.

Among industrial exporters, Leonardo (Milan: LDO) looks interesting. The firm, formerly known as Finmeccanica, has been restructured over the last three years to focus on core aerospace and defence assets. The company is investing to achieve sustainable growth, including the development of the AW609 tiltrotor aircraft. The shares recently dropped after the firm cut its free cash-flow forecast, but this could be a good opportunity for a patient investor to wait out the turnaround.

Prima Industrie (Milan: PRI) develops industrial lasers and sheet-metal machinery. The firm's latest results showed sales of €450m, earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation of €45m and a strong order book of €185m. On a price/earnings (p/e)ratio of 15, it is an interesting prospect.

Italy has encouraged the development of renewable energy, which now supplies close to 40% of its electricity. Renewable firm ERG (Milan: ERG) looks interesting. ERG is predominantly a wind-industry specialist, but may be interested in adding to its small solar portfolio by acquiring RTR, a solar group with around 332MW of capacity that is being sold by private-equity group Terra Firma.

There are no bargains in the fashion sector, but Luxottica (Milan: LUX) is the world's largest eyewear company, owning many leading glasses brands and retailers. It will soon merge with France's Essilor, the largest maker of lenses to produce a vertically integrated behemoth (the resulting firm will be listed in France, but Luxottica's founder will be the largest shareholder). Regulators in Europe and the US waved the deal through last week, which is probably bad for competition, but good for shareholders. On a p/e of 25, Luxottica is not cheap, but it's a good business that will soon have an even stronger market position.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Frederic is an investment analyst. He started his career at JP Morgan in Paris. He has more than ten years of experience investing in private equity and also worked with the 3i debt management team investing in private debt. He is an ACCA member and a CFA charterholder. He graduated from Edhec Business School.

-

Inheritance tax investigations net HMRC an extra £246m from bereaved families

Inheritance tax investigations net HMRC an extra £246m from bereaved familiesHMRC embarked on almost 4,000 probes into unpaid inheritance tax in the year to last April, new figures show, in an increasingly tough crackdown on families it thinks have tried to evade their full bill

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debt

Governments will sink in a world drowning in debtCover Story Rising interest rates and soaring inflation will leave many governments with unsustainable debts. Get set for a wave of sovereign defaults, says Jonathan Compton.

-

Why Australia’s luck is set to run out

Why Australia’s luck is set to run outCover Story A low-quality election campaign in Australia has produced a government with no clear strategy. That’s bad news in an increasingly difficult geopolitical environment, says Philip Pilkington

-

Why new technology is the future of the construction industry

Why new technology is the future of the construction industryCover Story The construction industry faces many challenges. New technologies from augmented reality and digitisation to exoskeletons and robotics can help solve them. Matthew Partridge reports.

-

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?

UBI which was once unthinkable is being rolled out around the world. What's going on?Cover Story Universal basic income, the idea that everyone should be paid a liveable income by the state, no strings attached, was once for the birds. Now it seems it’s on the brink of being rolled out, says Stuart Watkins.

-

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolio

Inflation is here to stay: it’s time to protect your portfolioCover Story Unlike in 2008, widespread money printing and government spending are pushing up prices. Central banks can’t raise interest rates because the world can’t afford it, says John Stepek. Here’s what happens next

-

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?

Will Biden’s stimulus package fuel global inflation – and how can you protect your wealth?Cover Story Joe Biden’s latest stimulus package threatens to fuel inflation around the globe. What should investors do?

-

What the race for the White House means for your money

What the race for the White House means for your moneyCover Story American voters are about to decide whether Donald Trump or Joe Biden will take the oath of office on 20 January. Matthew Partridge explains how various election scenarios could affect your portfolio.

-

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?

What’s worse: monopoly power or government intervention?Cover Story Politicians of all stripes increasingly agree with Karl Marx on one point – that monopolies are an inevitable consequence of free-market capitalism, and must be broken up. Are they right? Stuart Watkins isn’t so sure.