A simple way to stockpicking success

Taking a global approach to the 'Dogs of the Dow' investment strategy could yield big profits. Tim Bennett explains how it works, and reveals the markets most likely to profit.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

The Dogs of the Dow' is a well-known investment strategy that involves buying the most beaten-up stocks in the market, betting that they'll bounce back. Now, reports Bloomberg, a paper from David M Smith, associate professor at the State University of New York, suggests the strategy can be taken global you can earn superior long-term returns by buying the world's worst-performing stock-market indices, using low-cost exchange-traded funds (ETFs). So how does this Dogs of the World' strategy work?

The logic behind the original Dogs strategy is to buy the stocks in any given index the Dow Jones, or FTSE 100, say with the highest dividend yields. A high yield suggests the stock is out of favour with investors (because when prices fall, the yield rises, assuming that the dividend payout stays the same). Why buy such battered stocks? Because markets often overreact.

When investors get fearful, they sell first and think later. By buying these unpopular stocks, you are betting their prices will rebound, returning a quick profit. You get a decent dividend thrown in, assuming it isn't cut. The strategy has a reasonably good track record. But how does it work if applied to global markets?

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Taking the dogs global

There are some big differences between the Dogs of the World' and the classic Dogs of the Dow' strategy. But both are based on the principle of mean reversion' the idea that the most beaten-up stocks and markets won't stay that way forever, but will return towards fair value'.

Smith's paper looks at 45 national stock markets, as measured by the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) equity indices database. The MSCI indices represent both developed and emerging markets, although Smith notes that mean reversion tends to be strongest in emerging markets. This is because developed markets are more efficient': data on under or over-valued assets is transmitted more quickly between investors, resulting in fewer price abnormalities and faster corrections.

For 18 of the markets, data are available back to 1970. The rest become eligible for the study from the year when an MSCI index was first published for them. As with the Dogs of the Dow strategy, to make it into the selection, an index has to have been among the five worst performers over the previous year. However, while the stock-picking strategy turns the stocks over fairly rapidly, Smith's version is longer-term.

He takes a five-year holding period and assumes an investor drips 20% of their total planned investment in at the start, and 20% a year over the following four years. As Smith notes, "If the investor commits a full allocation to the five worst-performing markets from the previous year, and holds for five years, the investor forfeits the chance to take advantage of potential mean reversion using markets that perform worst in year one, year two, year three and year four."

The mechanics

Here's how it works. Taking the previous year's performance up to 31 December, you allocate 20% of your portfolio equally to the five worst-performing markets and keep 80% in cash. At the end of year one, you find the five worst-performing markets for that year and allocate another 20%, keeping 60% in cash. This continues until you are fully invested, with 0% in cash, a point that is reached at the start of year five.

At the start of year six, you then take the very first 20% allocation, and reinvest it in year five's worst performers. "In this manner the portfolio is repopulated each year on a rolling basis," notes Smith.

But does it work?

It certainly does. Between 1971 and 2012, the Dogs of the World approach produced annual compound returns of 10.39%. That is nearly 1% higher than the 9.45% return on the MSCI benchmark a significant difference.

There is one caveat: the Dogs portfolio is more volatile than a portfolio made up solely of the benchmark (this is known as a higher standard deviation of returns' in other words, the portfolio moves up and down a lot more). However, there is also a measure called the Sharpe ratio, which compares risk-adjusted returns between portfolios. Using this measure, there is little difference between the Dogs and the benchmark return. To translate that into English, the Dogs generate sufficient returns to justify the extra risk.

Now, a critic would argue that having to make a rolling investment in as many as five poorly performing markets each year is quite a fiddle, not to mention quite nerve-wracking. However, Smith re-tested the strategy using just the single worst-performing market and concludes that "investing for four to five years would have provided high returns, albeit with elevated volatility levels".

Have a punt on the dogs

The good news is that there are now ETFs available for 41 of the 45 markets reviewed by Smith (of which 24 are developed and 21 are emerging). These come with a cost in the form of a small bid-to-offer spread (the gap between the buying and selling price) and an annual management fee. Yet an investor who followed his strategy, rather than just buying and holding a broader global index, would enjoy compounded annual returns 246 basis points (2.46%) higher than the index.

If you fancy giving it a shot, based on the first quarter 2013 MSCI performance, the latest Dogs are Spain (LSE: EWP) down 6.4%; Italy (NYSE: EWI) down 9.7%; Russia (NYSE: RSX) down 3.6%; China (NYSE: PEK) down 4.5%; and Korea (NYSE: EWY) down 4.6%.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Tim graduated with a history degree from Cambridge University in 1989 and, after a year of travelling, joined the financial services firm Ernst and Young in 1990, qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1994.

He then moved into financial markets training, designing and running a variety of courses at graduate level and beyond for a range of organisations including the Securities and Investment Institute and UBS. He joined MoneyWeek in 2007.

-

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?

ISA fund and trust picks for every type of investor – which could work for you?Whether you’re an ISA investor seeking reliable returns, looking to add a bit more risk to your portfolio or are new to investing, MoneyWeek asked the experts for funds and investment trusts you could consider in 2026

-

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continue

The most popular fund sectors of 2025 as investor outflows continueIt was another difficult year for fund inflows but there are signs that investors are returning to the financial markets

-

Fundsmith Equity: a setback for a high-quality portfolio

Fundsmith Equity: a setback for a high-quality portfolioAdvice Rupert Hargreaves explains why investors should focus on Fundsmith Equity’s process rather than its losses

-

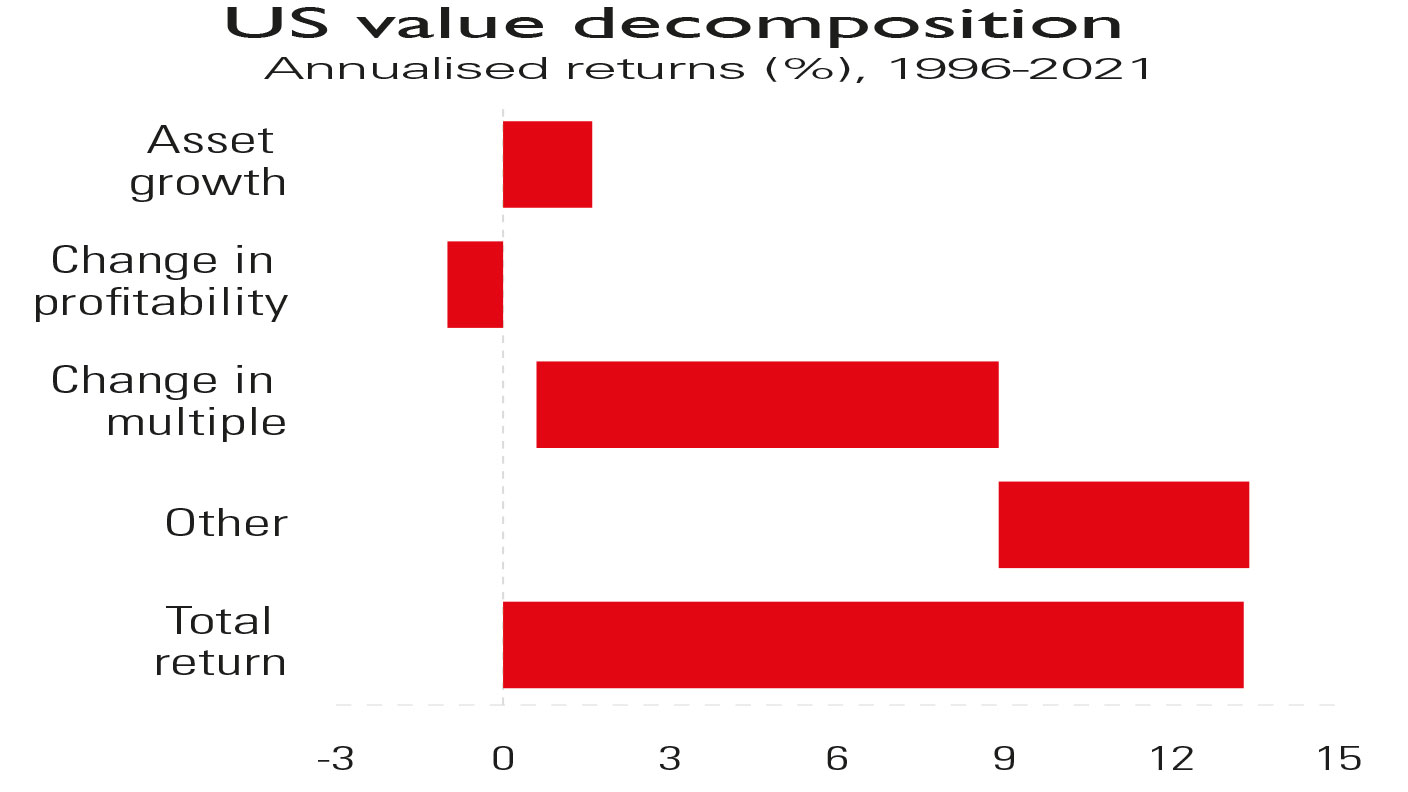

Value stocks: when cheaper isn’t cheap enough

Value stocks: when cheaper isn’t cheap enoughAdvice Value stocks will probably beat growth stocks in the years ahead, but that won’t necessarily mean high returns, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

Index provider

Glossary Stockmarket indices such as the FTSE 100 play a huge role in investment. But where do they come from and who maintains them?

-

How to build your own ultimate tracker fund

How to build your own ultimate tracker fundAdvice Efforts to build the “ultimate” tracker fund reveal how easy it is to over-complicate your asset allocation.

-

Bank on financial stocks with this investment trust

Bank on financial stocks with this investment trustTips Banks, though not British banks, look set for a strong rebound, making this investment trust worth researching.

-

Five funds to help you invest in a new Europe

Five funds to help you invest in a new EuropeTips Growth stocks are a much bigger part of European markets than many investors realise. These five funds will help you buy in.

-

Ethical investing: how to find an ESG tracker fund

Advice The number of ethical exchange-traded funds is growing ever larger – David C Stevenson outlines your options.

-

What is an emerging market, and should you invest in them?

What is an emerging market, and should you invest in them?Emerging markets can be a great way to add diversification to your investment portfolio, but what is an emerging market, and is now a good time to buy into them?