Value stocks: when cheaper isn’t cheap enough

Value stocks will probably beat growth stocks in the years ahead, but that won’t necessarily mean high returns, says Cris Sholto Heaton

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

“Value versus growth” is one of the easiest frames through which we can look at investing styles. Yes, it is a simplistic divide (see below): no investor can ignore valuations nor how earnings are likely to evolve. But it still says something about the psychology of an investor: do you favour a solid chance of profits today or the riskier possibility of a bigger gain in the future?

Splitting markets into growth and value also shines a useful light on trends. The MSCI World Growth index has beaten its value counterpart by six percentage points per year over the past decade, which is remarkable, but by more than sixteen points per year over the past three years, which is barely believable. With the growth index now on a forecast price/earnings of almost 30, compared with 13 for value, it’s hard to see how that can be repeated.

Investors want excitement

Value against growth is not the only long-standing anomaly to struggle lately. History also suggests that stocks with lower share-price volatility tend to outperform more volatile ones on average, yet the S&P 500 Low Volatility index (which holds the 100 least volatile stocks in the main US benchmark) has lagged the S&P 500 by 3.5 percentage points per year over ten years and almost ten percentage points per year over the past three years. No matter how you break it down, you can see the preference for glamorous, volatile growth stocks over anything duller.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Yet neither value nor low volatility have performed badly in absolute terms. The World Value index has returned an acceptable 9%-10% per year over three, five and ten years. The S&P 500 Low Volatility has returned 15% per year over three years and 12%-13% over five to ten years. This makes it hard to be confident that we can expect value stocks or low-volatility stocks to do well in absolute terms when the environment changes, because in many cases they have not done worse than expected up to now – they’ve simply been outstripped by a boom in growth.

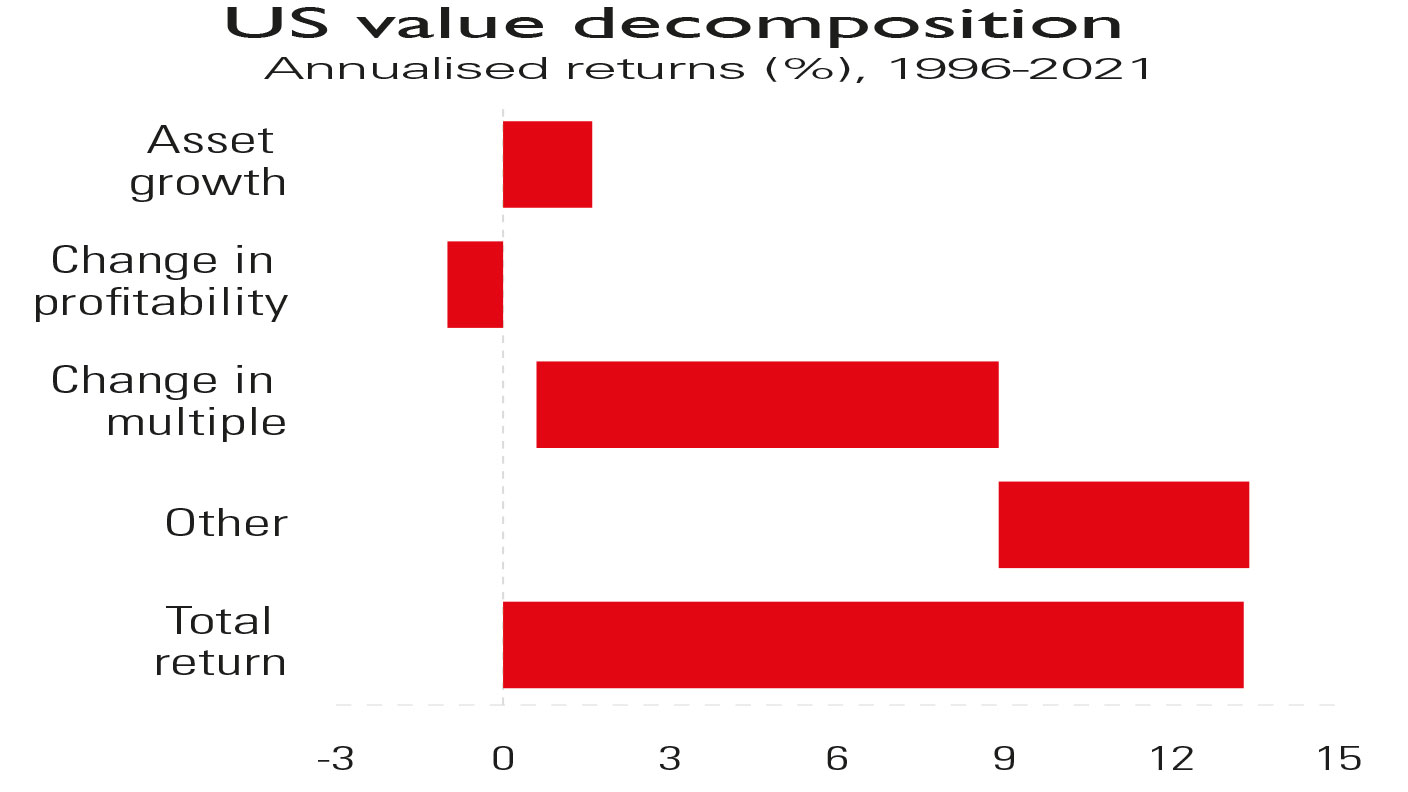

In particular, much of the return from value stocks usually comes from improving valuations as investors become less negative about their prospects, not through growth or increased profitability (see the chart above from Verdad Capital, which shows that about two-thirds of the total return in US value over the last 25 years came from changes in valuations). Today, value is not especially cheap in absolute terms, even if it is relatively cheap compared with growth. That will make it harder to benefit from the tailwind of improving valuations. Thus while value – and low volatility – will probably do better relative to growth, only a few genuinely unloved sectors (perhaps oil) seem likely to deliver impressive absolute returns.

The difference between growth stocks and value stocks

Investors in stocks can follow a number of distinctively different approaches – often referred to as styles – when deciding which companies to buy. The two styles that are most frequently used to classify investors are growth and value.

Growth investors look for companies that are expected to grow their earnings faster than their sector or the wider market. They will often be willing to buy shares on valuations that appear quite high compared to other companies if they believe that these may be justified by future profits. This approach places more emphasis on the firm’s potential, as opposed to its current financial situation.

Value investing is the opposite. Value investors focus on companies that appear to be cheap today (or sometimes stocks that should be cheap in the very near future if the business recovers after a recession or crisis). While growth investors are typically mostly concerned with earnings, value investors will often look for stocks that trade at a discount to book value (assets minus liabilities) or offer high dividend yields.

Some investors view the distinction between growth and value as artificial. A successful growth investor still needs to be confident that a company is not so overvalued that its earnings can’t justify the price they are paying. A value investor needs to consider whether a stock is cheap because the underlying fundamentals of the business are faltering and will lead to reduced profits, financial distress or bankruptcy in future.

That said, growth versus value provides an easy way to divide the market into stocks that are popular and high-priced and those that are out of favour and trade on lower valuations. Historically, the value segment of most markets have tended to beat the growth segment over the long run (which may be attributed to exuberant investors overvaluing potential growth). However, in the past decade, growth has handily beaten value.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?