The best way to find cheap stocks

The CAPE ratio is a useful tool to finding the cheapest markets to put your money, says Tim Bennett. Here, he explains how it works, and reveals the best-value countries to invest in now.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Investing success can't be reduced to one calculation it's not that simple. But if you were to put a gun to my head and force me to choose one, I'd go with the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio (CAPE). I am not alone in this among many others, Mebane Faber, portfolio manager at Cambria Investment Management, likes it too. So what's so good about it?

What is the CAPE?

The p/e is the ratio between the price of a stock or index, and a single year's earnings. As such, it gives you an idea of whether a market is expensive (a high p/e) or cheap (a low p/e). But there's one big problem earnings rise and fall from year to year with the ups and downs of the economic cycle. So how do you know that the e' figure in the p/e is representative?

For example, if company A has a share price of £5 and you use an earnings per share figure (earnings divided by the number of shares in issue) of 50p, the p/e is 10 (£5/50p). If the p/e of a similar share is 15, you might conclude that company A is relatively cheap. But what if company A's average earnings over a ten-year cycle are more like 25p? You'd get a p/e of 20 (£5/25p) not such a good deal.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This logic led to the CAPE a measure first devised by Yale professor of finance Robert Shiller and sometimes therefore called the Shiller p/e. He argued that a ten-year average earnings figure gives a much better view of whether a market is cheap or expensive.

What is it saying now?

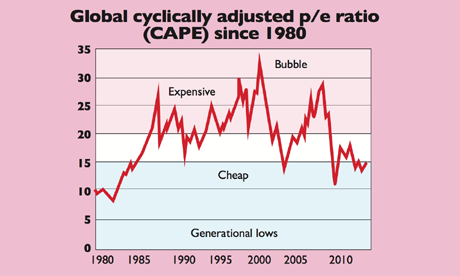

Faber has looked at the CAPE across a wide range of countries. In the chart, you can see the average CAPE for countries worldwide, stretching back to 1979. It shows that stocks are on a CAPE of about 15 neither particularly expensive or cheap. However, when you drill down into specific countries, it gets interesting.

Countries to avoid at the moment based on their CAPEs include North America (22.5) and parts of South America (Chile is on 21, Colombia 31, Peru 32, Mexico 21). One notable exception is Brazil (11) and another is Argentina (5).

Meanwhile, there are lots of bargains to be found in battered Europe. They include Greece (3), Ireland (5.8), Italy (6.8) and, slightly further afield, Russia (6.8). Clearly, these countries are cheap for a reason.

Argentina has many economic woes while the weaker European countries have the threat of a splintering euro hanging over them. As for Russia, the political risks involved in the region have kept investors wary for some time.

Yet as Faber has noted in the past, buying markets when their CAPE is at these low single-digit levels has historically been a route to big gains in the long run. That's because, eventually, the CAPE should revert to the mean' in other words, rise to somewhere closer to its long-term average, pulling prices up with it.

We're not saying these investments aren't risky but if you can invest for the long term and don't stake all your money on them, it's worth having at least a little exposure.

One way in is via exchange-traded funds (ETFs). For example, you can buy into Italy using the iShares FTSE MIB (LSE: IMIB) with an expense ratio of 0.35% and Greece with the Global X FTSE Greece 20 (NYSE: GREK). It has an expense ratio of 0.65%. Or you could play Brazil with the iShares MSCI Brazil (LSE: IBZL) at an expense ratio of 0.74%.

Russia can be accessed using the iShares MSCI Russia Capped Swap (LSE: RUSS), which aims to deliver the performance of the MSCI Russia index while limiting exposure to any single company (expense ratio 0.74%).

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Tim graduated with a history degree from Cambridge University in 1989 and, after a year of travelling, joined the financial services firm Ernst and Young in 1990, qualifying as a chartered accountant in 1994.

He then moved into financial markets training, designing and running a variety of courses at graduate level and beyond for a range of organisations including the Securities and Investment Institute and UBS. He joined MoneyWeek in 2007.

-

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax says

Average UK house price reaches £300,000 for first time, Halifax saysWhile the average house price has topped £300k, regional disparities still remain, Halifax finds.

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King