EU Economy

The latest news, updates and opinions on EU Economy from the expert team here at MoneyWeek

-

London claims victory in the Brexit wars

Opinion JPMorgan Chase's decision to build a new headquarters in London is a huge vote of confidence and a sign that the City will remain Europe's key financial hub

By Matthew Lynn Published

Opinion -

No peace dividend in Trump's Russia-Ukraine peace plan

Opinion An end to fighting in Ukraine will hurt defence shares in the short term, but the boom is likely to continue given US isolationism, says Matthew Lynn

By Matthew Lynn Published

Opinion -

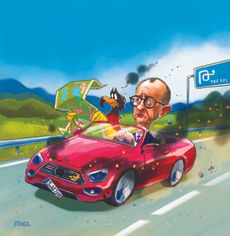

How Germany became the new sick man of Europe

Friedrich Merz, Germany's Keir Starmer, seems unable to tackle the deep-seated economic problems the country is facing. What happens next?

By Simon Wilson Published

-

'It’s time to close the British steel industry'

Opinion The price tag on British steel is just too high. It's time for Labour to make a grown-up decision and close down the industry, says Matthew Lynn

By Matthew Lynn Published

Opinion -

The secret behind Sweden’s success

Opinion Sweden's stock market is in rude health, says Max King. Why can't Britain follow suit?

By Max King Published

Opinion -

European bank stocks bounce back

Opinion European bank stocks were part casualty and part cause of Europe’s lost decade. Now it’s clearly turned the corner, says Cris Sholto Heaton

By Cris Sholto Heaton Published

Opinion -

US stocks are more expensive than ever after Trump's tariffs

We don’t need to second-guess the effect of Trump's tariffs to think that the rest of the world offers better value

By Cris Sholto Heaton Published

-

'The EU Chips Act is another epic failure of state planning'

Opinion The European Chips Act has been a complete disaster. That holds a broader lesson for governments, says Matthew Lynn

By Matthew Lynn Published

Opinion -

Will the boom in defence spending drive economic growth?

Defence spending is soaring, and politicians in the UK and Europe are telling voters it will be a major boost to economic growth. But is that really the case?

By Simon Wilson Published