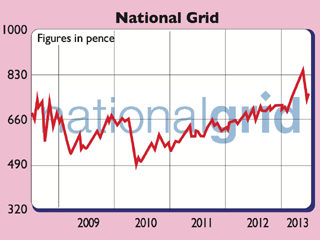

Is it time to pull the plug on National Grid?

Investors' favourite National Grid is on a collision course with the energy regulator over what it charges its customers. That could spell trouble for the attractive dividend. So is time to sell National Grid? Phil Oakley investigates.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Utility giant National Grid is seen as a classic defensive share: a low-risk business that can pay big dividends come rain or shine. So it's not difficult to see why it's popular with investors looking for income.

But can it keep paying bigger dividends in the future? On Monday, investors got a sharp reminder that even big, defensive utilities carry investment risks.

The energy regulator Ofgem and National Grid began negotiating over plans for spending and charges over the next few years. In short, Ofgem thinks the company can afford to do more with less, whereas National Grid begs to differ.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

As a result, analysts are wondering if a tough settlement with Ofgem might see National Grid forced to cut its dividend, tap shareholders for more money, or both.

So is it time to sell the shares? Or should you keep the faith in the National Grid dividend machine?

A high-stakes game for National Grid

National Grid owns the grids that transmit electricity and gas around the country. It also owns four regional gas distribution networks that pump gas into houses and businesses. It charges gas and electricity companies to use these assets. They then pass the costs on to us via our gas and electricity bills.

It's Ofgem's job to make sure we don't end up paying too much. So it caps the amount that National Grid can charge our energy providers. If the system is working, then National Grid should be able to provide a good service to its customers, while also giving a fair return to its investors. Investors then have an incentive to keep funding the company as it spends money on maintaining and upgrading the network.

So Monday was just the start of a high-stakes game that's played out every few years between regulated utilities and their regulators.

The company submits a spending plan, along with what it sees as a fair return on its assets. For example, it will set out its annual network running costs, along with any proposed improvements. These improvements are added to the company's regulated asset value (RAV) the amount invested in the company since privatisation.

So, if annual running costs are £1bn and the RAV is £10bn, and the required return to keep investors happy is 5%, then National Grid's annual revenue requirement is: £1bn + (£10bn x 5%) = £1.5bn. That dictates how much it can then charge its customers.

The company tries to put in as big a spending plan as it can. The larger its running cost allowance, the more scope it has to cut costs and so boost profits. Meanwhile, putting in bigger investment plans and a higher required return allow it to grow its RAV and make more money for investors.

Ofgem of course, knows all this. So it will scrutinise the spending plans and compare the costs to other utilities. And it usually responds with a lower spending plan and a lower allowed return on assets. The two then negotiate until the regulator gives its final decision.

So why is Ofgem acting tough?

National Grid wanted to spend just over £32bn between 2013 and 2021. Ofgem wants it to spend nearly £6bn less. It thinks that National Grid can be a lot more efficient and that some spending is unnecessary.

It's not hard to see why Ofgem is taking a tough stance. National Grid has made higher returns than had been expected during the last five years (see table below). So Ofgem now wants it to give back some of these higher profits to customers.

Also with interest rates at historic lows, Ofgem argues that a business like National Grid doesn't need to make as high returns on its regulated assets as it has been.

| Electricity Transmission Grid | 5.1% | 5.6% | 0.6% | 4.6% | -1.0% |

| Gas Transmission Grid | 5.1% | 7.3% | 2.3% | 4.4% | -2.9% |

| Gas Distribution Networks | 4.9% | 5.7% | 0.8% | 4.3% | -1.4% |

So is the dividend safe?

Ofgem's final decision won't be known until December. But looking at National Grid's finances, it's not unreasonable to ask whether it can maintain its dividend. After all, water companies United Utilities and Severn Trent had to cut their dividends after the last regulatory review of their charges.

The company currently has around £20bn of net debt (debt less cash). Profits barely cover its interest payments twice. With lower future returns coming from its UK assets, a low-returning set of assets in the US, and a big spending programme to fund, a dividend that costs nearly £1.5bn a year is a big commitment to maintain.

At the moment, National Grid's dividend cover is only 1.3 times. So it's certainly not out of the question that the company might have to ask shareholders for more money, or cut its dividend. It wouldn't be the first time in 2009, it asked shareholders for £3.2bn.

Of course, the threat to the dividend is one reason why the shares yield just over 6%. And it's possible that the two sides will reach a deal that is more favourable to National Grid. After all, this is the first bout of negotiating.

However, it's hard to see the shares making much progress from here while the main reason for holding them the high dividend continues to be questioned. If you own the shares, I wouldn't rush to sell them. But if you're looking for a new stock to add to your income portfolio, I think there are better options elsewhere. We look at some potential high-yielding investments in the next issue of MoneyWeek magazine, out on Friday (If you would like to become a subscriber you can subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine).

This article is taken from the free investment email Money Morning. Sign up to Money Morning here .

Our recommended articles for today

Shares in focus: France's nuclear powerhouse

With nuclear power out of favour, shares in EDF are in the bargain basement. So, should you buy the French utility? Phil Oakley investigates.

Cash flow is key to investment success

The cash-flow figure in a company's profits statement attracts little attention. But it could save you from making an investment disaster. Tim Bennett explains how.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Phil spent 13 years as an investment analyst for both stockbroking and fund management companies.

-

Could Chinese investments race ahead in the Year of the Horse?

Could Chinese investments race ahead in the Year of the Horse?As the Year of the Horse begins, we highlight the trends and sectors that could make great Chinese investments for the coming Lunar year

-

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?With gold and silver prices having outperformed the stock markets last year, mining stocks can be an effective, if volatile, means of gaining exposure

-

Investing in the energy sector – is the reward worth the risks?

Investing in the energy sector – is the reward worth the risks?The energy sector used to offer predictable returns, but now you need to tread carefully. Is the risk worth it?

-

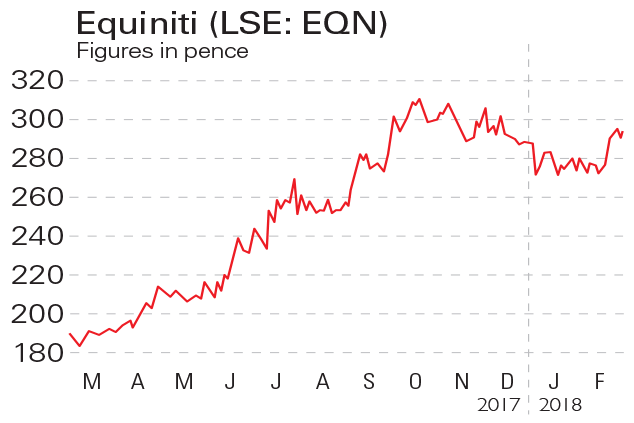

If you’d invested in: Equiniti and National Grid

If you’d invested in: Equiniti and National GridOpinion Financial services firm Equiniti has gone from strength to strength, while National Grid is facing uncertainty.

-

Shares in focus: Just how sheltered is National Grid?

Shares in focus: Just how sheltered is National Grid?Features The utility giant has been one of the better safe havens to own. So, should you snap up the shares? Phil Oakley investigates.

-

Shares in focus: A dependable dividend-payer

Shares in focus: A dependable dividend-payerFeatures This utility company pays out better than bonds for just a little more risk, says Phil Oakley.

-

Should you buy National Grid bonds?

Features National Grid has launched a new bond for the retail market. Its key attraction for hard-pressed savers is that over the ten years the capital value of the bond rises in line with the RPI. So should you buy it?