Revealed: the countries with the most generous pensions

The UK state pension is often criticised for failing to deliver a comfortable retirement. So, how does our pension system compare to other countries - which countries are most generous, and at what age can you claim a state pension?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The UK state pension has surged in recent years, thanks to the triple lock mechanism, and now pays out £221.20 per week for someone receiving the full new state pension.

But it is often criticised for still being too low. Even those who receive the full state pension of £11,502 a year face a shortfall of almost £3,000 to maintain a “minimum” standard of living.

According to pension industry guidelines, a single pensioner needs £14,400 a year to have a minimum lifestyle in retirement, rising to £43,100 for a "comfortable retirement".

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So, how does our state pension compare to our European counterparts and other countries like America and Australia?

Which are the most generous pensions, and how do state pension ages differ around the world? Do any other countries have a triple lock?

We look at how pensions compare to the average wage in each country, plus the criteria to qualify for a state pension.

Plus, check out our interactive map at the end of this article to see at-a-glance how state pensions compare in various countries.

Most generous pensions

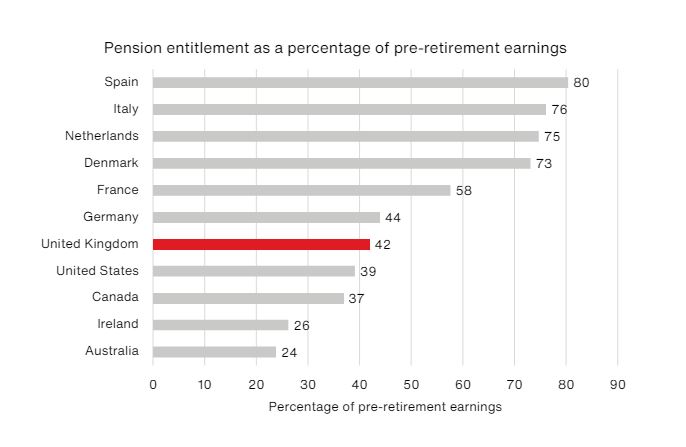

We asked pensions consultancy Aon to investigate the pensions on offer in different countries.

It looked at state pensions plus other mandatory or widespread pensions to give a comprehensive overview of the sort of benefits someone would receive in retirement.

For example, for the UK, Aon assumes the person receives a state pension plus a workplace pension based on the minimum auto-enrolment level of 8% of qualifying earnings.

In other countries like Italy and Denmark there are widespread workplace pensions, while in Australia it is mandatory for employers to pay 11% of earnings into a pension scheme - employees can opt to pay an extra 4% on top.

Aon then looked at how these pension benefits compared to the average wage in 11 countries: UK, Ireland, Spain, Italy, Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, France, Australia, United States and Canada.

It found that Spain pays the highest pension relative to its average wage. So, a retiree who had worked on the average wage would receive a pension income of 80% of their pre-retirement earnings.

Italy and the Netherlands come next, at 76% and 75%. The UK is in 7th place, at 42%.

Someone earning the country’s average wage before retirement

For lower earners, the picture is slightly different, with Denmark emerging as the most generous pension system. A woman earning half the average wage in Denmark would receive pension benefits worth 117% of her pre-retirement earnings. So her pension would actually be bigger than her income when she was working.

Netherlands (87%) and Spain (80%) take the next two spots. The UK comes sixth, at 62%.

What about higher earners? For a woman earning twice the average wage before retirement, Italy pays the most, at 76% of pre-retirement earnings. The UK takes seventh place, at 28%.

In pound terms, Italy pays an equivalent pension of £44,000 a year for someone who earned twice the average wage, while the UK pays £25,000, based on Aon’s analysis of OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) figures.

“The expected pension in the UK tends to be above or in line with the other English-speaking nations - US, Canada, Australia and Ireland - for each of the three scenarios,” comments Colin Haines, European retirement partner at Aon.

But the UK seems to be less generous at paying pensions than Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and Denmark.

Why are the pension payouts so different?

In terms of some European counterparts having bigger pensions, Haines points to higher taxation levels. The income tax burden is higher in the Netherlands and Denmark than in the UK, for example.

Employers also foot more of the pensions bill in certain countries. In France and Spain, a greater proportion of the typical pension costs are borne by the employer than in the UK, according to Aon.

Becky O'Connor, director of public affairs at PensionBee, adds: "As a percentage of GDP, public spending on the state pension is lower in the UK, at 4.9%, than the OECD average, at 7.7%. If that is the basis of assessing generosity, then the UK seems less generous.”

Meanwhile, in some countries, such as the Netherlands and Denmark, the retirement age is projected to increase in line with life expectancy, and therefore workers are not expected to see their benefits until much later in their lives.

For a worker born in the year 2000, her state pension age is forecast to be 74 in Denmark, 71 in Italy, and 70 in the Netherlands. In contrast, her state pension age in the UK would be 68.

The changing picture of which country offers the biggest pensions relative to average wages is due to most countries having state pensions connected to earnings.

Spain, France, Germany, Italy, and the US all have earnings-related pensions. So, the more you earn, the higher your payout.

Denmark, Australia and Canada means-test their pensions, so the reverse is true: the less money you have, the higher your state pension.

“The UK is actually fairly unusual in that it has a flat-rate state pension. Only the UK, Ireland and the Netherlands have flat-rate pensions in the countries we looked at,” notes Haines.

It means that higher earners receive the same as lower earners - all other things being equal - so those on bigger salaries will find that their state pension shrinks as a proportion of their pre-retirement earnings.

“The UK has a good system in that it supports those on average or low earnings,” says Haines. “High earners have to do more themselves to boost their retirement benefits, such as contributing more into private pensions.”

State pension ages compared

France has the lowest state pension age, at 62 (it will soon rise to 64). This is followed by Canada and Spain, at 65.

The UK, Ireland and Germany have state pension ages of 66. The other countries all have a current age of 67.

O'Connor says the UK is “average” when it comes to the age at which people receive their state pension. “The main exception here is France, where people currently get the equivalent pension at age 62, although this is rising to 64 from 2032.”

She says that some countries are “a bit more evolved in how they view people who work for longer or face lower life expectancy” and can therefore access their pension earlier. They include France, Denmark, Germany and Portugal.

The UK state pension age will increase from May 2026, gradually rising to 67 for those born on or after April 1960. “It could go up higher if the government wants to manage the costs,” warns Haines.

How are the state pensions uprated?

While the UK seems to be middle of the pack for how its pension benefits relate to pre-retirement earnings, its triple lock policy makes it fairly unique - and generous.

The triple lock is a system of increasing the state pension every April by inflation, wage growth, or 2.5%, whichever is highest.

This month, the UK state pension rose 8.5%, with wage growth deciding the 2024 uplift. The full new state pension increased to £221.20 a week, from £203.85. This adds up to £11,502 a year, compared to the previous £10,600.

In contrast, other countries tend to have a single lock or a double lock. For example, Denmark and Germany have a single uprating mechanism (average earnings), while Spain, France, Ireland, the US and Canada uprate in line with inflation.

The Netherlands uses the minimum wage to adjust its state pension, according to Aon.

Australia is the only one to have a double lock (average earnings and inflation), while the UK is the only country with a triple lock, out of the countries we analysed.

O’Connor comments: “Our uprating system - the triple lock - is relatively generous. Most countries in the OECD uprate pensions in line with either just inflation or inflation or wages, whichever is higher. The addition of the 2.5% element in the UK is quite unusual. Additionally, many countries apply a smoothed measure to increases to avoid anomalous increases, as we have recently experienced in the UK.”

Last year the state pension rose by a record 10.1%, whereas the year before it only grew by 3.1%.

Haines adds: “The triple lock is a fairly unique, and generous, feature of the UK state pension system. The flat-rate payment, plus the ability to buy National Insurance credits, makes it even more unique.”

What’s the criteria to get a state pension in different countries?

To qualify for a full UK state pension, you need 35 years’ National Insurance contributions (NICs).

As Haines mentions, it is possible to buy some if you don’t have the full quota. You can also get credits if you’re not working, for example by claiming child benefit or ticking a box on the form if you’re not claiming which will allow you to get NIC credits.

If you have between 10 and 34 years’ NICs, you’ll get a smaller state pension. If you have less than 10 years, you won’t get anything at all.

Compared to other countries, 35 years to earn a full pension seems like a pretty good deal. Only one country, Italy, has a lower number of years in order to pay a full state pension: 20 years.

The others have tougher criteria by demanding more years. In the Netherlands, you are only entitled to receive the maximum state pension if you have lived or worked there for at least 50 years. Germany demands 45 years, while France demands 42 years.

Interactive map: see how state pensions compare around the world

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Ruth is an award-winning financial journalist with more than 15 years' experience of working on national newspapers, websites and specialist magazines.

She is passionate about helping people feel more confident about their finances. She was previously editor of Times Money Mentor, and prior to that was deputy Money editor at The Sunday Times.

A multi-award winning journalist, Ruth started her career on a pensions magazine at the FT Group, and has also worked at Money Observer and Money Advice Service.

Outside of work, she is a mum to two young children, while also serving as a magistrate and an NHS volunteer.