Why taxpayers should stop supporting charities

Too many non-charitable charities are getting public money, says Merryn Somerset Webb. If you want to save the red squirrel, knock yourself out. But don’t expect the rest of us to pay for it too.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

There isn't that long to go until Christmas. That means I'm already getting buried in a pile of invitations to charity shopping mornings. I love these. I love almost everything to do with Christmas. I love all the handmade crafty stuff and the luxury stuff that you buy at these events. And I love the social aspect of shopping among a group of friends.

But there's one aspect of the whole thing I am not so sure about the charitable aspect.

Many people will have seen the story in the press last week about salaries at the big charities.Jasmine Whitbread, the chief executive of Save the Children, appears to be being paid £234,000 a year. And she is only one of 20 employees at the charity making more than £100,000 year. This isn't unusual. The head of Marie Stopes International gets £290,000, for example.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

You might think this is perfectly reasonable after all, charities need talent as much as big companies, and talent costs money. But I wonder how much else you know about the charities sector as a whole. I suspect everyone should read a new book from David Craig: The Great Charity Scandal (out on Amazon soon). It is not, as he is at pains to point out, an attack on charity itself (this is definitely a good thing). It is an attack on the UK's charitable system which has allowed not far off 200,000 charities employing more than a million people and spending some £80bn every year.

What are the main charges against them?

First, massive duplication and inefficiency. What's the point in having Breakthrough Breast Cancer, Breast Cancer Care and the Breast Cancer Campaign if they all have to prepare their own accounts and have their own very expensive bureaucracies? Why aren't they forced to merge? And why are there at least four charities (and possibly more I got bored of looking them up) devoted to red squirrels?

Second, the fact that so little of what they raise goes towards actual charitable expenses. I know of some charities who spend more keeping their final salary pension schemes (these are still bizarrely common in charity land) on the road than on their advertised activities. The pay problem is becoming increasingly common, too.

And third, what we think of as charitable activities are not the same as what many charities think of as charitable activities. Far too many of our big charities spend significant percentages of the cash we give them on political campaigning think Oxfam (which spent more than £20m on this last year), the RSPCA and the RSPB rather than helping the poor and sick (which, surely, is the point?).

None of this would particularly matter if the charitable sector was funded entirely by the post-tax income of private individuals. But it isn't. According to Craig, 27,000 British charities are reliant on the government for three-quarters of their income.

And all charities are reliant on the taxpayer one way or another. We (and the EU) give them direct subsidies (£137m to Save the Children last year, says Craig). We give them tax relief on all their income from donations and investment returns, and capital gains tax relief too. And of course, we give them Gift Aid.

I've written about this before(seehere, here, and here), but every time you tick the Gift Aid box, the Treasury has to dig deep to reallocate tax (to the tune of around £1bn a year) already paid into its coffers to your favoured charity: at the margin, the money flows out of the hands of our struggling NHS and into the seemingly bottomless pit of squirrel problems.*

Worse, the state has no control over the activities of these tax-revenue receiving organisations: they get our money and can do more or less what they like with it.

The key point is this: there are too many charities being at least part financed by the state which are not and should not be on the taxpayer's priority list. We need to pay for the basics of good government before we pay for anything else.

So if we must have tax relief for charities at all (and I am not sure we should) it is, as I said last year, time to distinguish between what is a charity that fits into the brief of the state and is hence a tax-revenue deserving charity, and what is not.

Soup kitchens? Yes. Cancer research? Mostly. Macmillan Cancer Support? Yup. Literary festivals? No. Opera? No. Theatre? No. The Brownies? No. Youth clubs in deprived inner cities? Yes. Donkeys? No. Red Squirrels? No really, no. Think tanks? No. Save the rhino? No. Private schools? No (a voucher scheme would be better). Personal/family foundations? No. Horse sancturies? No.

You get the idea. If you are in any doubt, read Craig's book.

*Oddly it isn't only people but charities who don't seem to recognise that Gift Aid is a transfer of cash from the taxpayer via the government to the charitable sector. Here's one charity on the matter: "The Red Squirrel Trust does not receive government or any other funding, so money to keep the charity running comes from donations, sponsorship, fund-raising, gift aid and grants." What, I wonder, do they think Gift Aid is?

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?

Can mining stocks deliver golden gains?With gold and silver prices having outperformed the stock markets last year, mining stocks can be an effective, if volatile, means of gaining exposure

-

8 ways the ‘sandwich generation’ can protect wealth

8 ways the ‘sandwich generation’ can protect wealthPeople squeezed between caring for ageing parents and adult children or younger grandchildren – known as the ‘sandwich generation’ – are at risk of neglecting their own financial planning. Here’s how to protect yourself and your loved ones’ wealth.

-

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updating

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updatingOpinion The Romans introduced pensions, and we still have a similar system now. But there is one vital difference between Roman times and now that means the system needs updating, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do better

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do betterOpinion Pensions auto-enrolment has vastly increased the number of people in the UK with retirement savings. But we’re still not engaged enough, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensions

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensionsOpinion UK house prices mean owning a home remains a pipe dream for many young people, but they should have a comfortable retirement, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

How to avoid a miserable retirement

How to avoid a miserable retirementOpinion The trouble with the UK’s private pension system, says Merryn Somerset Webb, is that it leaves most of us at the mercy of the markets. And the outlook for the markets is miserable.

-

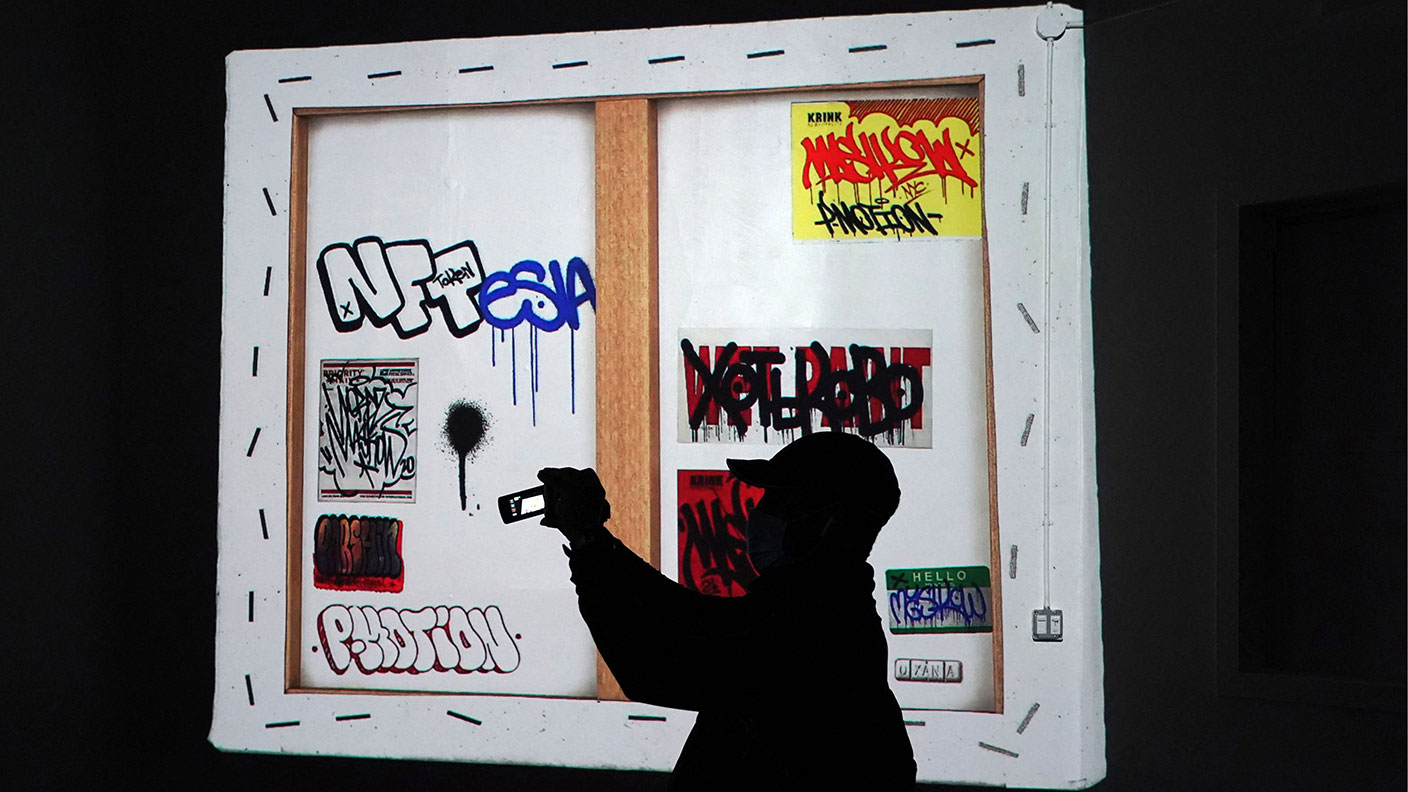

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investments

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investmentsOpinion The first batch of child trust funds and Junior Isas are maturing. But young investors could be tempted to bet their proceeds on digital baubles such as NFTs rather than rolling their money over into traditional investments

-

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accounts

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accountsOpinion Negative interest rates are likely to mean the introduction of fees for current accounts and other banking products. But that might make the UK banking system slightly less awful, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensions

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensionsAdvice As more and more people lose their jobs to the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to deal with it, there’s one bunch of people who won’t have to worry about their future: politicians, with their generous defined-benefits pensions.

-

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house prices

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house pricesOpinion Stamp duty is an awful tax and should be replaced by something better. But its temporary removal is driving up house prices, says Merryn Somerset Webb.