No doubt about it – the new student loans scheme is a tax

Don't be fooled - the new scheme from the Student Loans Company is a tax. And for some, it's a pretty high one at that.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

I wrote recently that the new scheme to finance students from next year looks more like a tax than a loan system. Not everyone agreed. Several readers wrote in to point out that the system is really no different to that for a mortgage in that it is taken out voluntarily and has interest-bearing repayments. The only real difference is a good one: that those who are relatively unsuccessful never have to pay the loan back.

I don't buy it. So in last week's Spectator, I looked at exactly how the system works. It goes like this.

From 2012, all student tuition fees will be automatically paid by the Student Loans Company. When the students graduate, and are earning more than £21,000, they will start to pay 9% of their income over to the Student Loans Company via the PAYE system.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The interest rate starts at the RPI (retail price index) inflation rate and steadily rises as you earn more: once you are earning £41,000, the interest rate will be RPI plus 3%. You will pay every year, regardless of how much your original loan was and you will not be able pay the whole thing off early - even if you have the cash to do so.

This isn't a bit like a mortgage. For starters, while some degrees are clearly voluntary, the important ones aren't: if you want to be a lawyer, a doctor or an engineer you will have to have a degree, and you will have to pay the 9%. You can rent a house as and when you need one. You can't rent an education it has to be paid for in full up front.

Next, note that the payments on your mortgage don't go up as you earn more they are absolute, not relative to income.

Finally, the fact that the relatively unsuccessful never have to pay a penny towards their tuition is a vital part of the puzzle. I'd go so far as to say that's it's the clincher in defining these charges as taxes rather than loan repayments. I have never yet heard of a case in which a mortgage lender has decided against repossession, and let someone off paying back their debt, because they aren't doing as well as everyone else in their office. But that is exactly how a progressive tax system works: the successful pay more and the unsuccessful pay less.

Here we have a charge on graduates taken via the income tax system; that there is no way out of; and that goes up with your income. There are elements of a loan in here but for most people, these kinds of repayments are going to feel more like a tax. And for those who end up paying it for the full 30 years, a pretty high one at that.

From 2015, if you are a graduate and you earn £21,000 you will end up paying a marginal income tax rate of 41%. If you earn over £42,475, you'll be paying 51%. This may not matter (after all, what is the alternative?). But it does explain why there is such a scrum to get into university this year.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

BrewDog investors have lost everything - are there better ways to back small firms?

BrewDog investors have lost everything - are there better ways to back small firms?The collapse of BrewDog has called into question how useful crowdfunding is as an investing strategy and whether there are better ways to profit from small firms and start-ups

-

One million more pensioners set to pay income tax in 2031 – how to lower your bill

One million more pensioners set to pay income tax in 2031 – how to lower your billHundreds of thousands of pensioners will be dragged into paying income tax due to an ongoing freeze to tax bands, forecasts suggest

-

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updating

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updatingOpinion The Romans introduced pensions, and we still have a similar system now. But there is one vital difference between Roman times and now that means the system needs updating, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do better

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do betterOpinion Pensions auto-enrolment has vastly increased the number of people in the UK with retirement savings. But we’re still not engaged enough, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensions

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensionsOpinion UK house prices mean owning a home remains a pipe dream for many young people, but they should have a comfortable retirement, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

How to avoid a miserable retirement

How to avoid a miserable retirementOpinion The trouble with the UK’s private pension system, says Merryn Somerset Webb, is that it leaves most of us at the mercy of the markets. And the outlook for the markets is miserable.

-

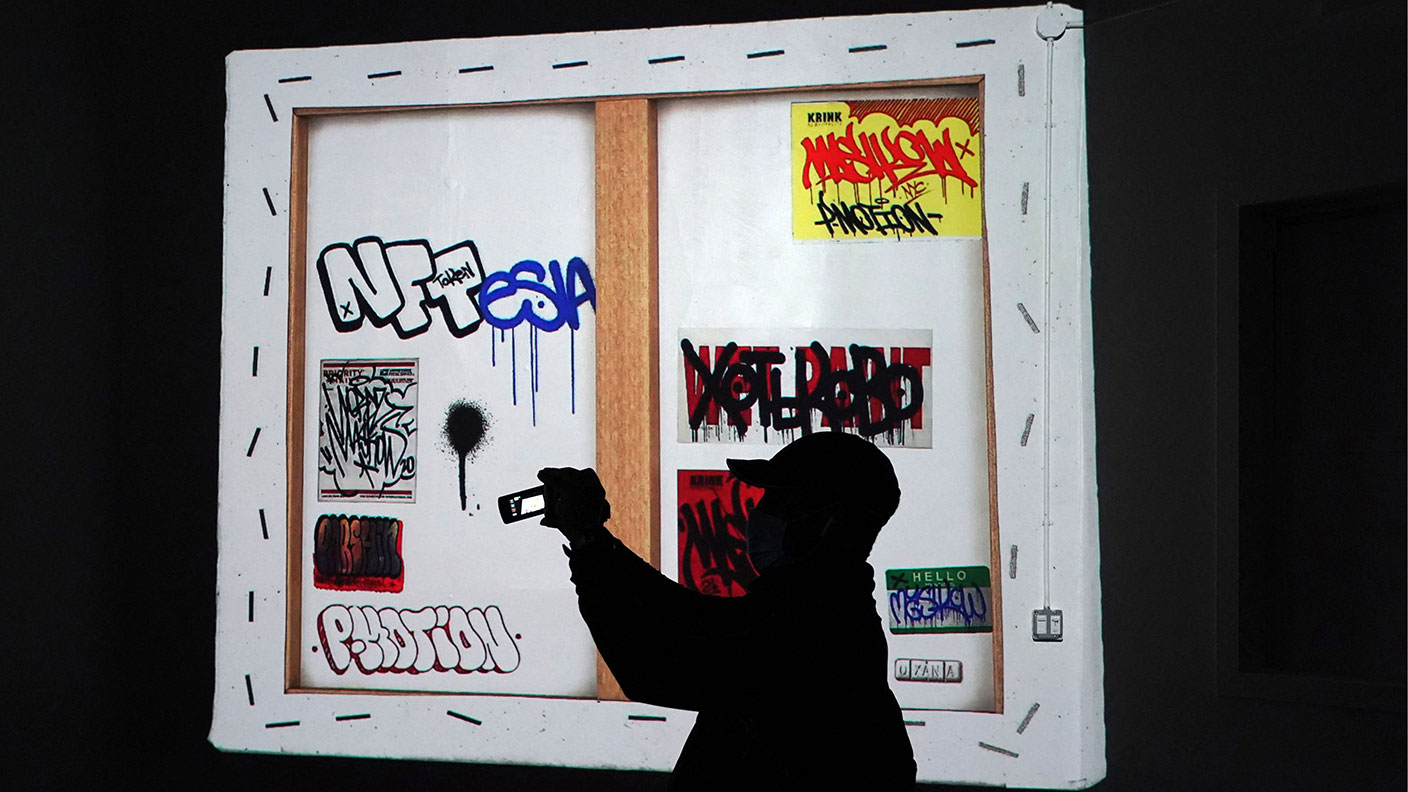

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investments

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investmentsOpinion The first batch of child trust funds and Junior Isas are maturing. But young investors could be tempted to bet their proceeds on digital baubles such as NFTs rather than rolling their money over into traditional investments

-

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accounts

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accountsOpinion Negative interest rates are likely to mean the introduction of fees for current accounts and other banking products. But that might make the UK banking system slightly less awful, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensions

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensionsAdvice As more and more people lose their jobs to the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to deal with it, there’s one bunch of people who won’t have to worry about their future: politicians, with their generous defined-benefits pensions.

-

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house prices

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house pricesOpinion Stamp duty is an awful tax and should be replaced by something better. But its temporary removal is driving up house prices, says Merryn Somerset Webb.