Financial education: laudable but useless

Instead of wasting time on financial education, we would be better off teaching our children basic maths, and making financial products easier to understand.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The answer to every financial problem these days is usually said to be financial education. How do we stop people getting ripped off by pay day lenders? Education.

How do we get people to save into a pension? Education.

How do we stop people being charged so much by their fund managers that however much they save they still don't have a pension? Education.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

How do we prevent people from taking out the wrong kind of mortgage? Education.

How do we get people to choose use up their ISA allowances, to get the right bank account, to buy life insurance that actually works? Education, education, education.

But is this really a good answer? We suspect not.

I said last week that harping on about education offers an endless get out clause to the financial industry. Push ahead with it to the exclusion of other things and we will end up with what my colleague John Stepek calls a "financial arms race" in which providers compete to come up with ever more ridiculous products to bamboozle their apparently increasingly sophisticated clients.

Imagine the response from the industry in 20 years' time, when miserable small business owners complain to whatever regulator is in control by then about being done over by the banks. "He passed his consumer finance paper at school", they will say, " he should have known what an interest rate swap is."

It has long seemed to us that instead of going on and on about financial education, we would be better off teaching our children maths rather better (note just how shockingly far down we come in this OECD table), incorporating key concepts such as compound interest and the like into lessons and crucially also making financial products easier to understand.

This is not a consensus opinion. I asked a conference audience a few weeks ago how many of them thought that personal finance education in schools was vital. They all put their hands up. So I was thrilled later on to find an ally.

I met Richard Thaler, author of Nudge, and he told me that he was going to offer our ideas a little support. And so he has. In his most recent New York Times column,Thaler completely destroys the idea that financial education is of any use at all to people who aren't intrinsically interested in finance. He quotes the results of 167 studies into attempts to teach people to be less financially clueless. The result? While financial education might be laudable, "it isn't particularly helpful."

Even the most time intensive courses had "no discernable effects" on student understanding "just two years later". This, says Thaler, isn't particularly surprising. After all, we don't remember much of what we learnt at school: "unless you use chemistry at work you probably don't recall much about ionic bonding."

So if financial education is not the answer to helping people navigate the world of money what is?

Thaler has a few good suggestions. The first is "just in time education". As people don't remember stuff for long, they need quick bursts of tuition just before they make a decision: so offer mortgage mornings to late 20 somethings and lessons on student loans to A level students. Otherwise, we might just give people simple rules of thumb to follow ("save 15% of your income, get a 15 year mortgage if you are over 50") and hope for the best.

But his final solution is ours as well. Find a way to make products much more simple for the consumer. We don't, after all, expect people to understand the language of how cars work when they buy them. Salesmen simply explain the price and the product in ordinary language (you can sit seven people in it, it goes quite fast, it cost £14,990) and that's that.

There is no real reason for financial products to be any different.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?

-

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updating

Our pension system, little-changed since Roman times, needs updatingOpinion The Romans introduced pensions, and we still have a similar system now. But there is one vital difference between Roman times and now that means the system needs updating, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do better

We’re doing well on pensions – but we still need to do betterOpinion Pensions auto-enrolment has vastly increased the number of people in the UK with retirement savings. But we’re still not engaged enough, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensions

Older people may own their own home, but the young have better pensionsOpinion UK house prices mean owning a home remains a pipe dream for many young people, but they should have a comfortable retirement, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

How to avoid a miserable retirement

How to avoid a miserable retirementOpinion The trouble with the UK’s private pension system, says Merryn Somerset Webb, is that it leaves most of us at the mercy of the markets. And the outlook for the markets is miserable.

-

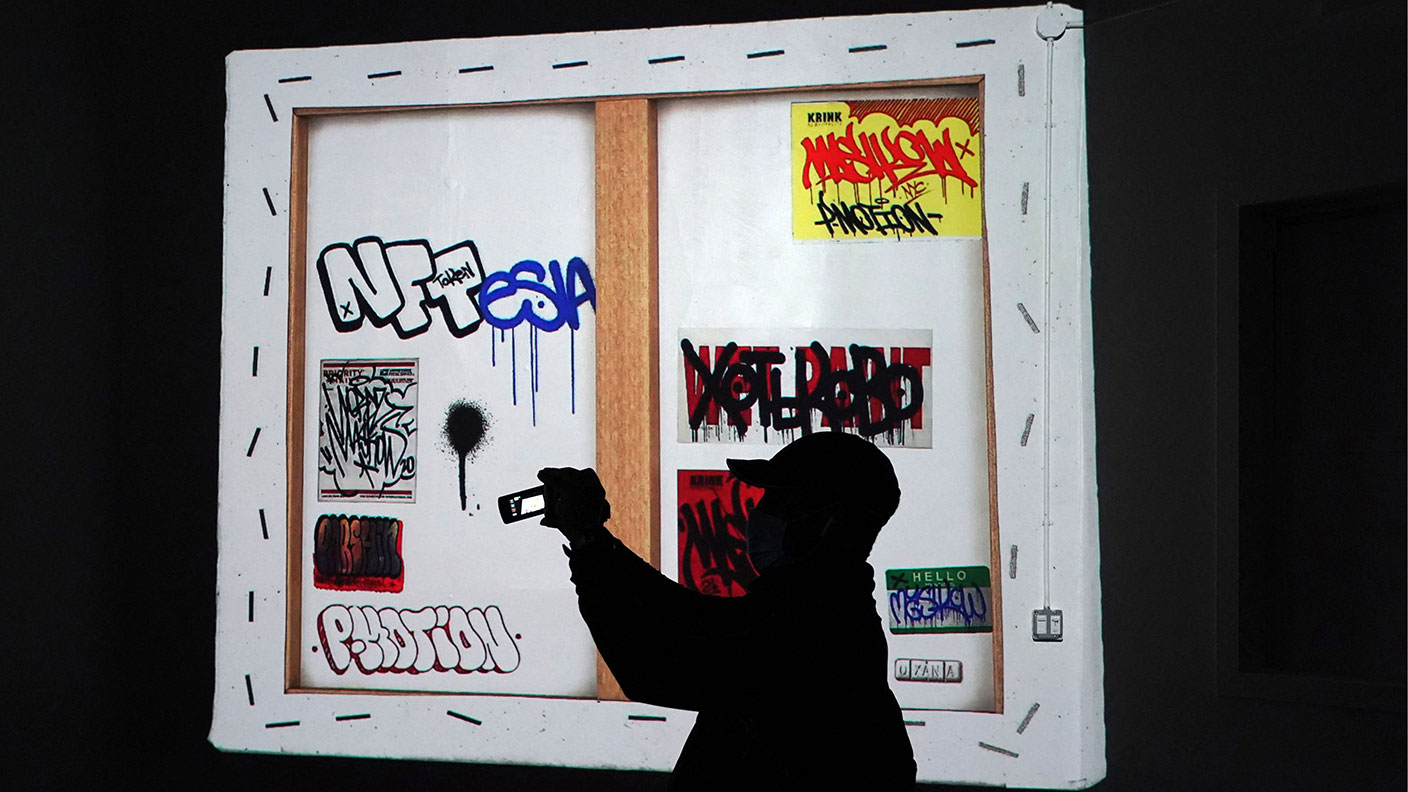

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investments

Young investors could bet on NFTs over traditional investmentsOpinion The first batch of child trust funds and Junior Isas are maturing. But young investors could be tempted to bet their proceeds on digital baubles such as NFTs rather than rolling their money over into traditional investments

-

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accounts

Negative interest rates and the end of free bank accountsOpinion Negative interest rates are likely to mean the introduction of fees for current accounts and other banking products. But that might make the UK banking system slightly less awful, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

-

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensions

Pandemics, politicians and gold-plated pensionsAdvice As more and more people lose their jobs to the pandemic and the lockdowns imposed to deal with it, there’s one bunch of people who won’t have to worry about their future: politicians, with their generous defined-benefits pensions.

-

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house prices

How the stamp duty holiday is pushing up house pricesOpinion Stamp duty is an awful tax and should be replaced by something better. But its temporary removal is driving up house prices, says Merryn Somerset Webb.