Lessons for investors from Big Tech's previous golden era

The forerunners of today's tech stock titans dominated the 1960s and 1970s. Former Xerox senior manager Dr Mike Tubbs was there and explains what investors can learn from those companies' mistakes.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Investors often fail to appreciate just how big Big Tech is. The world’s four largest technology stocks –Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft – account for around 21% of the market capitalisation of America’s S&P 500 index. In other words, just 0.8% of the index’s companies comprise more than a fifth of the index.

But this isn’t the first time huge, fast-growing tech shares have dominated stockmarkets. The 1960s and early 1970s marked another Big Tech era. Markets were in thrall to the Nifty-50, 50 fast-growing large-caps that captured the headlines. Four of them were famous tech stocks: IBM, Kodak, Polaroid and Xerox. Their history, and the parallels we can draw with today’s market backdrop, hold valuable lessons for the investors and tech titans of the 2020s.

Turning down Xerox’s copier

All four tried to move onto each other’s turf, just as today’s tech companies have been doing. The star of the four was Xerox. From 1963 to 1972 Xerox’s shares rose by 1,463%. Shares in Haloid (which became Xerox in 1961) gained 120,000% between 1936 and 2000. Xerox’s first office copier – the 914 – was launched in 1961. But in the late 1950s, Xerox approached IBM to help fund and sell its copier after its launch. IBM employed management consultants AD Little to assess the prototype copier’s potential.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

AD Little said the copier was too big for an office and too heavy for IBM’s typewriter-salesmen to transport, so IBM opted not to assist and Xerox marketed it alone. Xerox cleverly placed the machines with customers for free, charged a monthly rent covering the first 2,000 copies, and printed money by billing five cents a copy after that. I joined Xerox as a senior manager in 1973 and saw at first hand the events I describe below.

Copying Polaroid’s camera

Imaging and office automation were the main competitive battlegrounds. Kodak and Polaroid competed in imaging. Kodak was the global market leader in photographic film, paper and related chemicals. Polaroid, which invented polarisers (optical filters that let only certain lightwaves in) for sunglasses and 3D-imaging, made large instant-photography cameras.

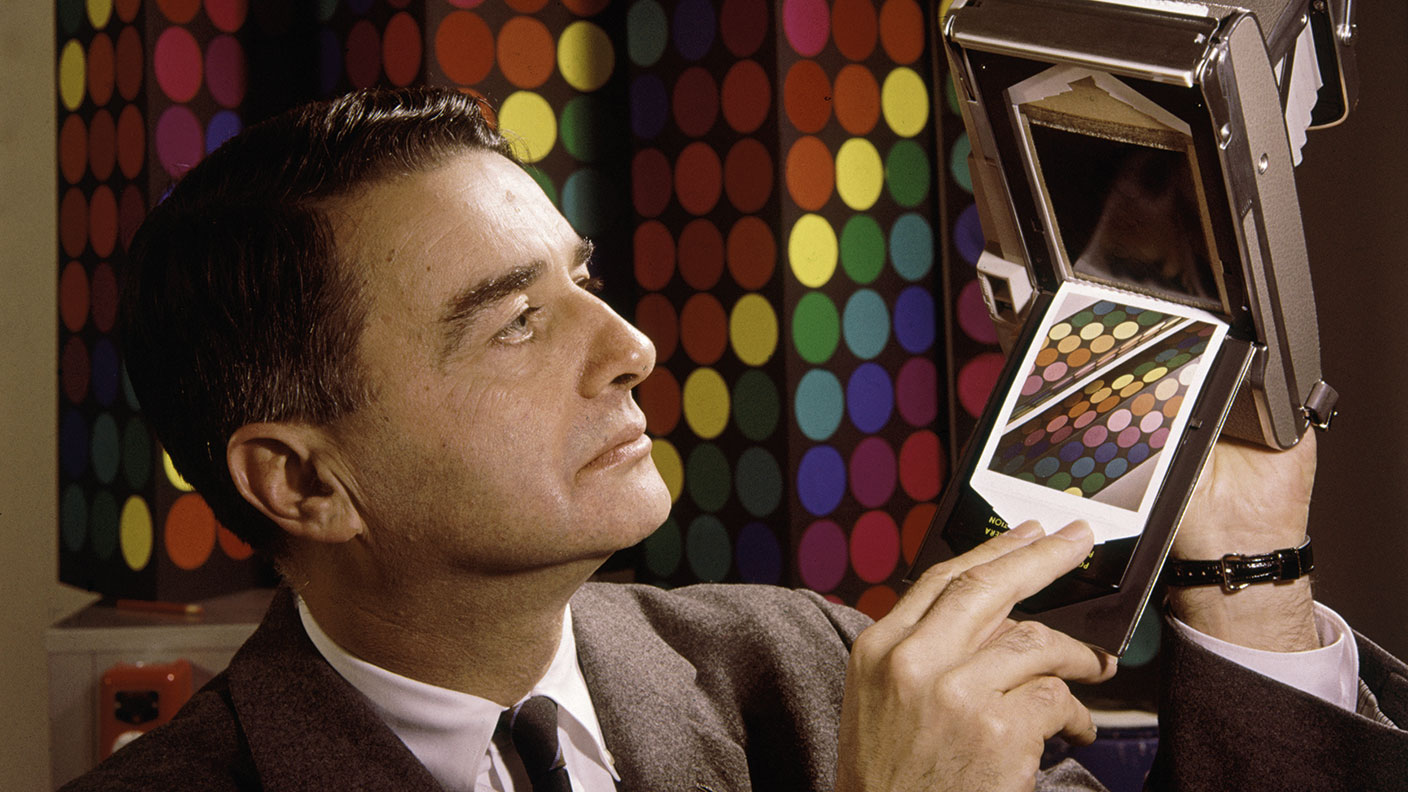

The launch of Polaroid’s “pocket-sized” SX-70 colour instant-camera changed everything. Edwin Land, founder of Polaroid, was the Steve Jobs of his day. He wanted a pocket-sized SX-70 so, at its 1972 market launch, he produced it from his jacket – specially made with larger-than-standard side pockets. The SX-70 single-reflex instant camera automatically produced a fully-developed colour print in one minute and was an instant success.

Kodak’s team of 1,400 instant photography developers were stunned by the SX-70’s size and performance. They ditched their now obsolete prototype and copied Polaroid’s approach. Polaroid sued for patent infringement in 1976 and won. It was awarded $925m in damages and Kodak was obliged to cease production of all instant cameras and films.

Kodak’s next mistakes

While Kodak was struggling to compete with Polaroid in instant photography it made an even bigger mistake. A Kodak research and development (R&D) engineer, Steve Sasson, invented the first portable digital camera in Kodak’s laboratories in 1975. But Kodak decided not to develop and market it because it feared it would cannibalise its massive revenues from film photography. But digital photography did emerge and drove both Kodak and Polaroid into bankruptcy – in 2012 and 2001 respectively.

IBM, Kodak and Xerox competed in office automation. IBM dominated mainframe computers (large ones used for bulk data processing) and had a typewriter division. Xerox was the market leader in office copiers. Both companies wanted to offer a complete range of office automation so IBM introduced an office copier in 1970. Xerox sued IBM for patent infringement, won the case but was awarded only $25m.

In the 1970s both introduced word processors. Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Centre (PARC) developed the world’s first personal computer in 1972 (the Alto) complete with mouse, user-friendly interface and networking. In 1975 Kodak launched its Ektaprint copier aimed at Xerox’s profitable mid-range market segment. The Ektaprint’s speed and copy quality were superior to Xerox’s existing machines. Xerox had no inkling of the pending launch despite both firms having R&D laboratories in Rochester, New York with their staff mingling socially. I remember examining an Ektaprint in Xerox’s competitive products laboratory soon after launch and being impressed by its many major innovations and copy quality.

How did these companies fare moving onto each other’s turf? Firstly, Kodak moved tentatively, only launching its Ektaprint copier in six US cities. This gave Xerox time to launch a competing product with similar performance. Kodak then took seven years to launch the Mark II Ektaprint but Xerox launched an upgrade of its new model the year before. Xerox failed with its personal computer, the Alto, which was never marketed.

Xerox misses a huge trick

However, the Apple Macintosh and Sun Workstation were both modelled on the Alto. So why did Xerox not commercialise it? Firstly, because it was distracted and deterred by the purchase of Scientific Data Systems, a minicomputer company, in 1969; that division was closed down in 1975 with the loss of over $1bn. Secondly, Xerox’s top managers were from Ford and used to making modest improvements to existing products rather than launching new, innovative ones.

Xerox also failed to develop a timely small copier, partly because of thinner profit margins on smaller machines and because the small new-technology copier we developed within Xerox was burdened with large-copier specifications that delayed development and increased costs. That enabled Japanese companies such as Canon and Ricoh to launch small copiers and move upmarket with larger machines.

Then Xerox decided to explore inkjet technology for small copiers and printers and asked me to head up an inkjet R&D laboratory; I declined since I did not want to move my young family to the US. In 1968 the FTC (US Federal Trade Commission) charged Xerox with monopolistic practices (it had 90% of the US copier market). A consent decree was signed with the FTC in 1975 under which Xerox granted competitors patent licences at nominal royalties.

What investors and today’s titans can learn

What lessons can be drawn for today’s tech companies? First, if you develop a potentially world-beating product, do commercialise it (remember what happened to Xerox’s PC and Kodak’s digital photography). If you market it, do so wholeheartedly or the incumbent will match it before you gain substantial market share (Kodak’s Ektaprint). Do be aware of new or improved technologies that can take sales from your existing products (instant photography, Ektaprint improvements). If you try to copy a competitor’s product, do so without infringing its patents (Kodak/Polaroid, IBM/Xerox). And beware of regulators.

Internet and data are the battlegrounds for today’s tech companies. It all began when Apple introduced the Alto/Macintosh PC in January 1984 at a time when Microsoft had MS-DOS. Because Apple wouldn’t license its Mac software to others, Microsoft was able to develop Windows (launched in November 1985), which became the de-facto standard. IBM had used Microsoft to develop the operating system for its PC (launched August 1981), but failed to specify exclusivity, so Microsoft could sell its operating system to other computer makers.

In October 2001 Apple launched the iPod – a 21st-century version of the ubiquitous Sony Walkman. Sales boomed and 42% of Apple’s revenue in the first quarter of 2008 came from the iPod. Smartphones were the next battleground. In 2007 Nokia led the market in mobile phones. But although Nokia’s hardware was excellent, its software was not. That gave Apple the opportunity to introduce the iPhone in June 2007 and take market share. But Apple, as with the Mac, kept its mobile operating system to itself, giving Google the opportunity to introduce Android. Google was market leader in search and online advertising and wanted Search, YouTube, Maps and Gmail on mobiles. Enter Android in 2007 with the first Android smartphone (HTC’s) launched in 2008. Android has become a de-facto standard like Windows. It now has 86% of the market.

Microsoft badly missed the mobile opportunity. Samsung, using Android, became the number-one smartphone company in 2012 and has remained number one. In an echo of the Polaroid/Kodak case, Samsung was sued by Apple for patent infringement in 2011 with Samsung counter-suing. Apple eventually won damages of $539m in 2018. The next area of competition was data and the cloud. Amazon gained first-mover advantage by offering companies cloud storage and remains market leader. Microsoft’s recent renaissance stems from its adoption of cloud storage where it holds the number-two position.

Video streaming is another arena of competition. This was pioneered by Netflix, but Amazon (using Prime), YouTube (Google), Disney, Apple and others are all now competing with Netflix. Finally, remembering the FTC/Xerox case, tech companies need to be aware of regulatory issues. Microsoft was fined €561m by the EU for monopolistic practices in 2013 after it deleted a browser choice pop-up for Windows 7, having agreed in 2012 to include it. Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Amazon and Apple have all fallen foul of EU antitrust investigations in recent years. And the US Congress is expected to impose new regulations on Big Tech, which it sees as effective monopolies. Many analysts now expect these companies to be broken up – heralding an era of smaller

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Highly qualified (BSc PhD CPhys FInstP MIoD) expert in R&D management, business improvement and investment analysis, Dr Mike Tubbs worked for decades on the 'inside' of corporate giants such as Xerox, Battelle and Lucas. Working in the research and development departments, he learnt what became the key to his investing; knowledge which gave him a unique perspective on the stock markets.

Dr Tubbs went on to create the R&D Scorecard which was presented annually to the Department of Trade & Industry and the European Commission. It was a guide for European businesses on how to improve prospects using correctly applied research and development.

He has been a contributor to MoneyWeek for many years, with a particular focus on R&D-driven growth companies.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton