How Softbank went from a tech investor to a big hedge fund

Softbank, the Japanese technology investor, appears to be gambling rather than investing these days. Shareholders are rattled. Matthew Partridge reports.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

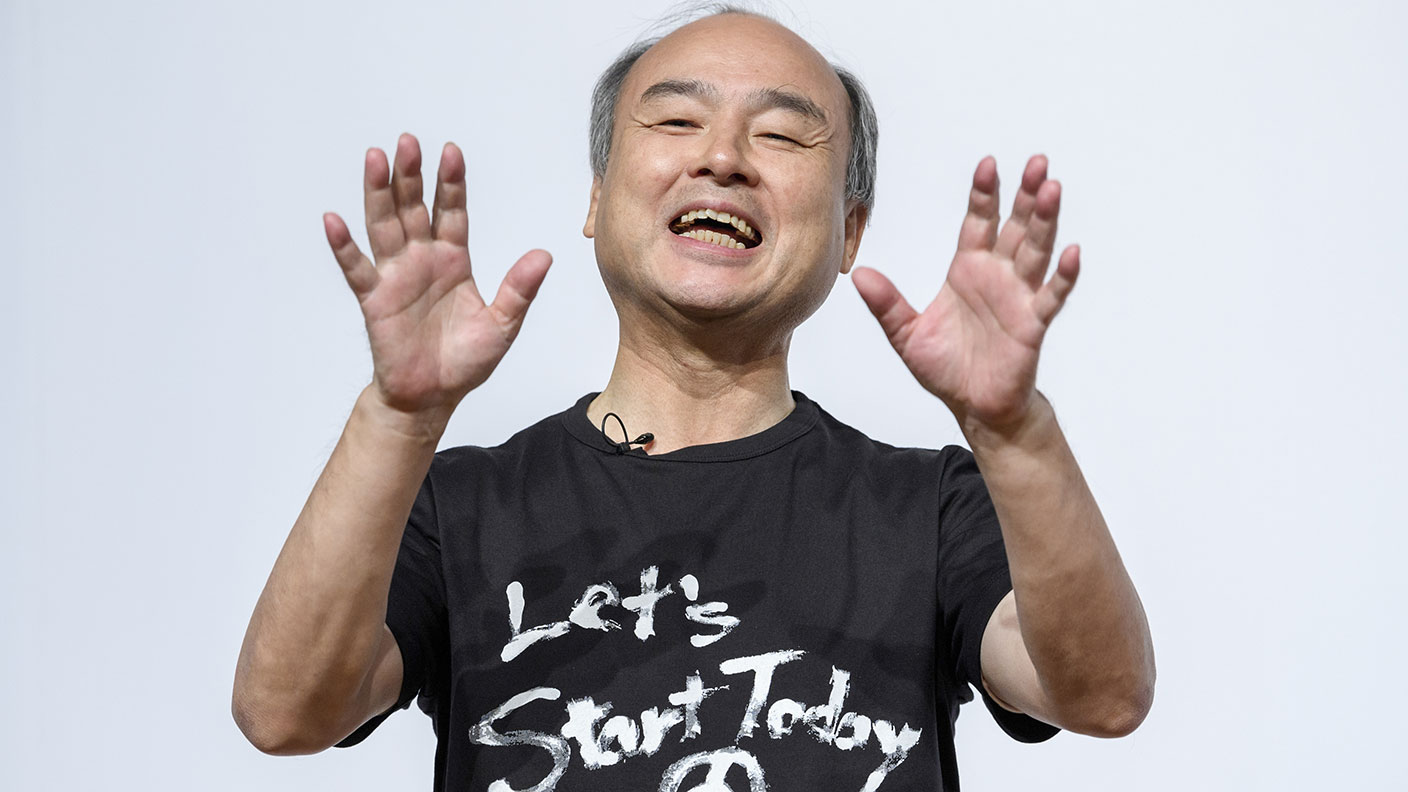

The Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, run by Masayoshi Son, is among the world’s “biggest and most controversial” technology firms, say Matthew Field and Hasan Chowdhury in The Daily Telegraph. While it is known to focus on “young, privately-held companies”, SoftBank is now revealed to have made large bets on publicly-traded tech companies too.

It purchased $4bn of call options on tech firms. These instruments, which allow it to buy a stock at a certain price, turned the firm into a “whale”: an investor so large they automatically drive the market up if they make a purchase.

SoftBank may claim to have made $4bn in paper profits from its unusual strategy, but it is unclear whether any money will remain once the dust clears, says Jennifer Hughes on Breakingviews. Already, a “sharp downturn” in US tech stocks at the end of last week has wiped more than 10% off the Nasdaq Composite index (see page 4).

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

At the same time, SoftBank’s own shares tumbled by 5% once its activities in the options market were revealed, cutting its market cap by $7bn. In any case, even if the deals make money, this is “beside the point”: SoftBank investors can bet on publicly-traded US tech stocks “without Son’s assistance”.

A poor record

It’s hard to disagree with investors who feel that not only is Son’s gambling luck unlikely to hold, but his company also shouldn’t be behaving like a “drunken hedge fund”, says Nils Pratley in The Guardian. After all, Son’s record on timing market movements over short periods “does not impress” given that he lost $70bn during the dotcom crash in the 2000s.

The entire episode suggests that Son now prefers the “fun” of “leveraged bets and short-term risk-taking” to the more complicated task of finding long-term opportunities. These latest revelations not only raise questions about Son’s judgement, which had been called into question before, but also underlines concerns about how “poorly governed” and “financially opaque” the Japanese tech group is, says Lex in the Financial Times. Even before the latest debacle, SoftBank’s reports were just a “mish-mash” of valuation swings – many of which have proven to be wide of the mark – and extracts from the reports of companies Softbank invested in. Investors need to realise that, despite SoftBank’s public listing and retail investor base, it is little more than a “big hedge fund”.

All these problems have resulted in SoftBank having a “deep discount” to its stated net assets, says Jacky Wong in The Wall Street Journal. Ironically, this discount had started to narrow from its March peak thanks to the prudent decision to sell or monetise $42bn-worth of assets to buy back shares and redeem debt. All the progress looks set to be reversed as the “lack of transparency” on this new investment gambit widens this discount further.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?

Should investors join the rush for venture-capital trusts?Opinion Investors hoping to buy into venture-capital trusts before the end of the tax year may need to move quickly, says David Prosser

-

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doing

Food and drinks giants seek an image makeover – here's what they're doingThe global food and drink industry is having to change pace to retain its famous appeal for defensive investors. Who will be the winners?

-

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woes

Barings Emerging Europe trust bounces back from Russia woesBarings Emerging Europe trust has added the Middle East and Africa to its mandate, delivering a strong recovery, says Max King

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton