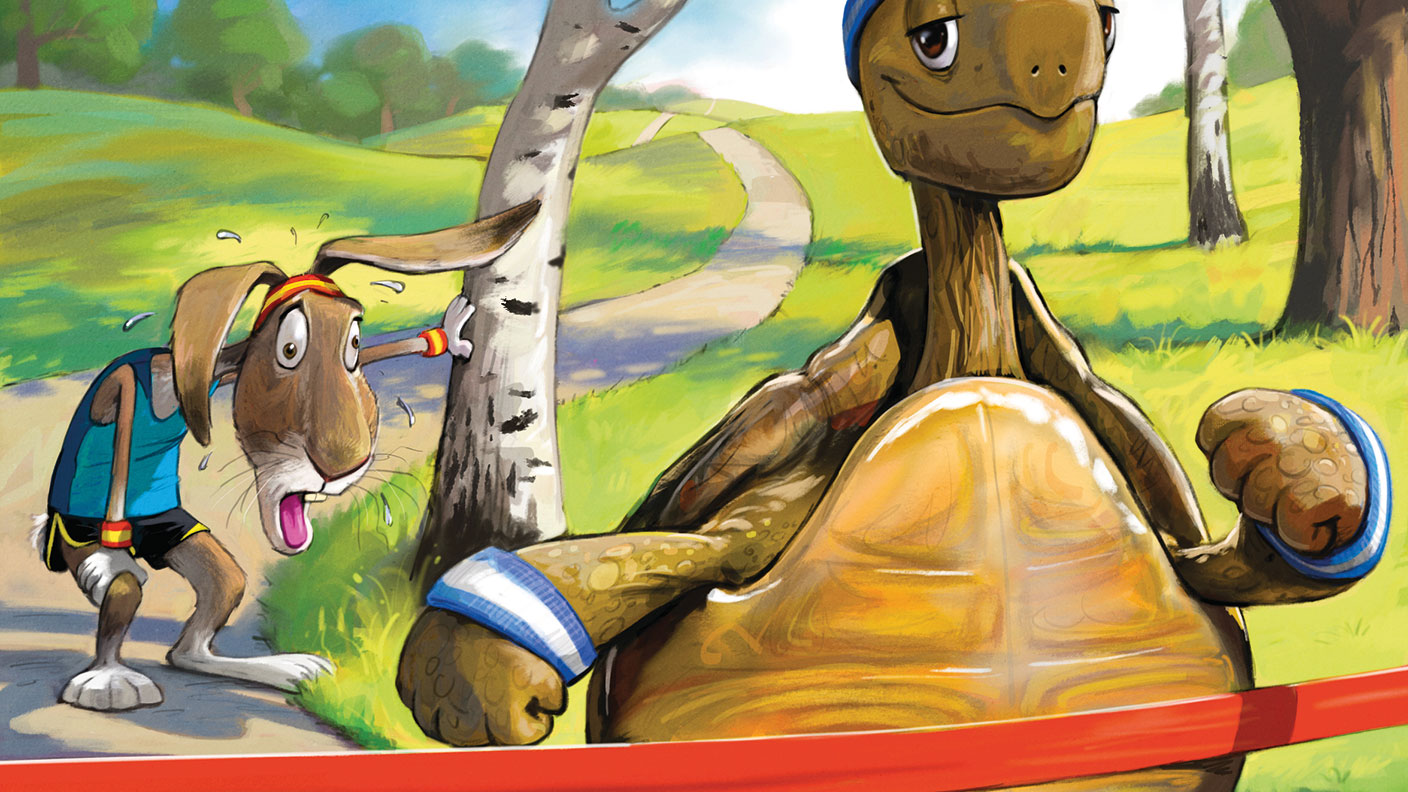

Slow and steady wins the race: five stocks to buy for the long term

Balancing quality and price is the key to successful investing, says Richard Beddard – both poor-quality stocks and overvalued top-notch ones are risky. Here are Britain’s best large and medium-sized companies

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Investment strategists generally posit that the higher the quality of a business, by which we mean the more profitable it is likely to be in future, the more it is worth paying for the shares. This is because future profits belong to shareholders, who will receive this future profit as dividends – or the profit will be invested back into the business to earn even more profit in the future. Investors can make above-average returns if they can find shares whose prices do not reflect their potential.

The goal of most investment analysis is to assess how much a company is worth, with a view to buying the shares for less. This is challenging in today’s markets, because low-quality businesses are difficult to value, while more predictable high-quality businesses seem expensive.

Investment versus speculation

Investors are putting a very high price on quality. For instance, according to SharePad, a data platform for private investors, Halma, which has grown relentlessly by acquiring safety-technology businesses, traded on a price/earnings (p/e) ratio in the twenties for much of the last decade. Today the shares cost nearly 50 times trailing earnings. Spirax Sarco, which makes steam systems used in industry and hospitals, and Dechra Pharmaceuticals, a producer of veterinary medicines, are also in this exalted category. Their performance and prospects have earned them p/es around 50.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

In a pandemic you can see why investors might be prepared to pay a premium for quality. In hard times poor-quality firms make losses, get further into debt, have to raise money from shareholders, or even go bust. The premium is a form of insurance against these risks. But by paying more for the shares, investors are swapping one kind of a risk for another. They are trading business risk for valuation risk.

If a highly priced firm goes off the rails, the effect on the share price can be dramatic because it is priced for strong growth – witness Avon Protection, formerly Avon Rubber. It owns a business that makes respirators for the armed forces and first responders. Last year it traded a second good business that supplied milking equipment for two companies making protective equipment: a division of 3M that makes body armour and Team Wendy, a helmet-maker.

The disposal and two acquisitions allowed Avon Protection to concentrate on its highly profitable military and first-responder markets, but the 3M acquisition appears to have been a disaster. A product has failed in testing and the company is preparing to write off some of its investment. In less than a year Avon Protection’s share price fell by 80% even though only the body-armour acquisition is affected.

The trade-off between quality and price

Benjamin Graham, widely regarded as the father of value investing and mentor of Warren Buffett, pinpointed this trade-off between quality and price.In one speech he described a U-shaped line on a chart. The chart’s horizontal axis measures the quality of businesses. At the extreme left are broken businesses with dire performance records and poor prospects. At the extreme right are fast growers widely perceived to be future winners. The vertical axis, meanwhile, measures how speculative stocks are, with the most speculative ones at the top.

Graham envisaged a U-shape on the graph, with the shares on the top left highly speculative because of their poor quality; but the ones in the top-right area being just as speculative because although they were top-notch, they were very vulnerable to high prices. It was the shares in the bottom of the U-shaped curve that Graham was interested in. These are shares in solid companies that were not overvalued. To Graham, these shares were investment-grade. Everything else was speculative.

My aim in this article is to bring you a selection of shares nestling safely near the bottom of the U. Just be warned: they may be somewhat dull. Shares that have caught the public’s imagination are rarely cheap, while underappreciated firms are unlikely to be famous. The excitement of turnarounds and runaway growth stories means that such companies are more likely to be overvalued.

Some investors also take comfort from owning shares in well-established businesses. All of the companies profiled here are members of the blue-chip FTSE 100 index or the FTSE 250 index of medium-sized companies. They have been listed for more than a decade and have corporate histories that go back much further. They are profitable, cash-generative, well financed and boast coherent strategies. If their p/e ratios do not put them in the bargain basement, they are at least not totally immodest. They are classic bottom-of-the-U-curve shares.

Bunzl

Distributor Bunzl (LSE: BNZL) is a one-stop shop for industry, commerce and public organisations. The easiest way of describing what it sells is to outline what it does not sell. It does not supply raw materials or components to manufacturers and it does not supply retail stock to shops, or food to restaurants.

Yet it supplies all these industries and hospitals, the construction industry and the public sector. It provides their everyday requirements, including vast amounts of packaging, cleaning products, health and safety equipment and healthcare consumables (medical equipment that must be discarded after use, such as rubber gloves).

Bunzl’s resilience is a function of two things: the products it sells, mostly consumables, and its scale. Customers require a reliable, cheap and efficient source of toilet paper or face masks, which is where Bunzl’s size comes into play. By gobbling up much smaller rivals, 174 of them since 2004, and allowing them to benefit from its global-procurement network and more efficient systems and warehouses, Bunzl drives prices down. Having expanded globally, it can supply multinational customers almost anywhere.

The essential nature of the products and Bunzl’s scale have served shareholders well. The company has grown profits at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9% over the last decade, while maintaining high levels of profitability. The 37% return on capital (a key gauge of profitability) it achieved in the year to December 2020 was exceptional, thanks to extraordinary demand for face masks, disinfectant and so on, but Bunzl’s average return on capital of 25% and high levels of cash conversion are still impressive. Bunzl is on a trailing p/e of 17.

Games Workshop

In the past few months Games Workshop’s (LSE: GAW) shares have suffered their biggest reversal since the first lockdown. In March 2020 traders mistakenly imagined that the miniature-wargames company might be negatively affected by the pandemic. Since 2016, though, the share price has risen by 2,000%. In trading terms, at least, not all investment-grade firms need be dull.

Games Workshop is a vertically integrated business, meaning it controls many of the activities required to bring the product to market instead of outsourcing them. It manufactures models of characters from the imaginary science fiction and fantasy worlds Warhammer 40,000 and Warhammer Age of Sigmar. It markets Warhammer through its own shops and website, as well as in magazines and an online community hosting cartoons and video tutorials. Although it also sells through independent hobby shops, Games Workshop has control over every aspect of the hobby, which can sometimes put it at odds with customers who would like the products to be cheaper, or to produce their own online content, which Games Workshop interprets as an infringement of its intellectual property. If this occasionally fractious relationship shows that Games Workshop can sometimes seem high-handed, it also demonstrates the passion of its customers.

These passions are stirred by product launches, the biggest of which are new editions of Warhammer. These attract great interest, but they can be followed by periods when the growth in demand tapers. Since Games Workshop bears the high fixed costs of factories and shops, profit is sensitive to changes in revenue and growth comes in spurts. We may be entering a period of slower growth, but long-term investors will appreciate that Warhammer is unique and enduringly popular. The group has achieved a near-40% average return on capital over the last ten years and profit has grown at CAGR of 22%. The stock is on a p/e of 25.

Howden Joinery

Howden Joinery (LSE: HWDN) is by far the biggest supplier of fitted kitchens in the UK. How it has achieved this since it was founded in 1995 should be the subject of business-school case studies. The idea that drove Howden’s founders was that it could better serve trade customers – small builders – by refusing to sell to retail customers. At the time most fitted-kitchen suppliers had trade counters around the side of their retail showrooms (many still do). But this meant a retail customer could pop around the corner and see whether the manufacturer was offering them a better deal than their builder. Specialists usually outcompete generalists and once Howdens had chosen to focus, it developed other trade-friendly policies. Small builders receive enough credit that they can often finish fitting a kitchen before they have to pay Howdens for it.

Howdens maintains near 100%-stock availability so builders do not experience hold-ups and it provides the builders with kitchen-design services so their customers can see how the kitchens will look. In return, the company does not have to maintain pricey showrooms or buy lots of television advertising, because its trade customers are its sales force. The genius of this symbiotic relationship is that, unlike retail customers who might replace their kitchen once a decade, the trade customer is a repeat customer.

This unique business model has turned Howdens into a very profitable enterprise. The company has achieved an average return on capital of 22% over the last decade and although profit has only grown at a 4% CAGR, the period ends unfavourably for Howdens in December 2020. Confronted by their grubby kitchens during the first lockdown, people wanted new kitchens, but Howdens couldn’t sell them and builders couldn’t install them.

Due to the gradual release of pent-up demand, revenue has jumped in 2021. Meanwhile, Howdens is increasing depot openings in France, where it hopes to mobilise small builders, who are underserved, just as they were here. The shares sell for 21 times earnings.

Next

Fashion and homewares retailer Next (LSE: NXT) has successfully navigated the shift from high street to internet shopping. It has profited during the pandemic and it is set to prosper after it. These achievements are connected. Most of Next’s revenue and profit come from the internet, which mitigated some of the damage caused by shop closures during lockdowns. Selling homewares as well as clothing also helped. Being an expert online retailer may have secured Next’s future, but the company also realised five years ago that the internet offered two new opportunities. These add to its promise as an investment.

Next saw that as an online retailer it would be easier to expand abroad in Europe as it would no longer have to roll out shops and concessions. It also worked out that on the internet competitors are only a click away, so rather than shut them out it embraced them, promising to become their cheapest route to market. The company was investing heavily to develop its own website and well-established logistics capability, which it inherited from its famous mail-order catalogue Next Directory.

Next thought it could help smaller retailers without the resources to develop their own capabilities and opened up its website to competing brands. Then it instigated a project dubbed Total Platform, which handles the online activities of fashion retailers, the website, the warehousing, the deliveries and the returns – for a fee.

With Total Platform, Next is helping four other retailers and investing in three; menswear brand Reiss is joining the platform in the new year, the biggest brand to come on board to date. While the growth of Total Platform is constrained as Next monitors the early adopters, tunes the service and earns the capital to expand the capacity of its warehouses, the project illustrates the company’s ability to reinvent itself under the leadership of Lord Wolfson, its CEO since 2001. While a lockdown-induced near-50% decline in profit in the year to January 2021 means the company has not grown over the last decade, it has recovered strongly in 2022. It is highly profitable, earning an average return on capital of 20%. The p/e ratio is 18.

PZ Cussons

PZ Cussons (LSE: PZC) gets the second half of its name from the famous soap brand it acquired in 1975 and the first half from the initials of its founders, George Paterson and George Zochonis, who established the business in Sierra Leone in 1884. Today it owns a range of hygiene, baby and beauty brands, including Carex handwash and Original Source shampoo.

It has not adapted particularly well to the increase in competition from discount retailers’ own brands and the vast choice available online, but has recently renewed its focus. Under new management it has slimmed down its international structure so it is no longer competing as a multinational consumer-goods manufacturer such as Unilever, but as a “multi-local”, putting most of its resources into a small number of market-leading products and the regions they lead in.

Cussons is not one of the brands it has identified as a “must-win” brand. It and all the other “portfolio” brands the company owns have a different purpose – either to generate cash to invest in top brands, such as Carex, or to give manufacturing and distribution critical mass in markets where it has a “must-win” brand. It has sold off most of its food labels, which has improved its financial position and allowed it to invest in digital marketing and sustainability.

PZ Cussons intends to become a “B-Corp” firm (one meeting high environmental and social standards) by 2026, which will require it to pass a rigorous audit of its impact on workers, customers, suppliers, the community and the environment. This will allow it to burnish its already strong environmental credentials and profit from mounting concern about the environmental and social impact of the products we use.

PZ Cussons had lost its way. It is the only company in this selection that had not grown over the decade prior to the pandemic, but it is probably turning things around from a position of strength. Not only has the company decided which of its brands are strongest, but it also has sound finances and has achieved an average return on capital over the last ten years of 21%, which suggests there is latent growth potential. As an investment, it may stray some way up the left arm of Benjamin Graham’s U-shaped curve into speculative territory, but there is probably more than enough substance to it. It is on a p/e of 15.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Richard Beddard founded an investment club before joining Interactive Investor as an editor at the height of the dotcom boom in 1999. in 2007 he started the Share Sleuth column for Money Observer magazine, which tracks a virtual portfolio of shares selected for the long-term by Richard. His career highlights include interviewing Nobel prize winners, private investors and many, many company executives.

Richard is freelance writer who invests in company shares and funds through his self-invested personal pension. He has worked as a teacher and in educational publishing, and is a governor at University Technology College, Cambridge. He supports the Livingstone Tanzania Trust, a charity supporting education and enterprise in Tanzania.

Richard studied International History and Politics at the University of Leeds, winning the Drummond-Wolff Prize for "distinguished work in the field of international relations".

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’

‘Why you should mix bitcoin and gold’Opinion Bitcoin and gold are both monetary assets and tend to move in opposite directions. Here's why you should hold both

-

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new look

Invest in the beauty industry as it takes on a new lookThe beauty industry is proving resilient in troubled times, helped by its ability to shape new trends, says Maryam Cockar

-

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?

Should you invest in energy provider SSE?Energy provider SSE is going for growth and looks reasonably valued. Should you invest?

-

Has the market misjudged Relx?

Has the market misjudged Relx?Relx shares fell on fears that AI was about to eat its lunch, but the firm remains well placed to thrive

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brands

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brandsConsumer brands no longer impress with their labels. Customers just want what works at a bargain price. That’s a problem for the industry giants, says Jamie Ward