How to invest in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease

The cost of caring for those with dementia is a growing problem for healthcare systems around the world. Any firm that develops an effective treatment could stand to make a fortune, reports Matthew Partridge.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Alzheimer’s disease is not only one of the top causes of death worldwide – it is also a condition that is “incredibly devastating” for people, says Martin Tolar, chief executive of biotech company Alzheon. It’s not just the victims who end up suffering, as the friends and family of those affected have to watch helpless while their loved ones lose their memories, their personality and the ability to carry out basic tasks. At present, most treatments “only deal with the symptoms of the disease, rather than altering the course”, but the encouraging news is that this is set to change, in as soon as the next five to ten years.

These breakthroughs can’t come too soon. The large number of people who now suffer from Alzheimer’s has created a “huge unmet demand” for better treatments, says Cassie Doherty of Parkwalk Advisors, a fund that specialises in investing in university spin-outs. In the UK alone, over 500,000 people have been diagnosed with the disease, which accounts for around two-thirds of all dementia cases (vascular dementia accounts for most of the rest). It’s a similar story across the entire developed world.

The direct cost of palliative treatments, plus the wider costs of the social and medical assistance that most Alzheimer’s patients end up requiring, represents a huge drain on health and social care budgets. Some estimates put the total expense of treating and caring for Alzheimer’s patients in the US healthcare system alone to be as much as $500bn per year. Such a figure may sound incredibly high, but Doherty agrees that it is “plausible” especially “when you take into account the costs of unpaid carers, such as family”.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The situation is likely to get even worse over the next few years as the number of patients is “growing quickly”. There is a strong, well-documented link between Alzheimer’s and age, with around one in every three people over 85 suffering from the disease, so an ageing population is much more susceptible to the condition. This combination of high costs and increasing cases means that there is a “real commercial opportunity” for anything can help doctors and healthcare workers deal with sufferers.

More efficient diagnosis

Before any treatment can be carried out, patients first have to be diagnosed with the disease. At the moment, the only way to definitely diagnose Alzheimer’s-related dementia is to carry out a brain scan (or in a few cases a lumbar puncture). However, since such procedures are expensive, costing up to £20,000, most healthcare systems tend to require patients to be assessed by several doctors before such a scan is approved. In the UK this follows a three-stage process, with a general practitioner (GP) first referring patients to a specialist, who then decides whether to order a scan.

This is inefficient, says Sina Habibi, co-founder of Cognetivity Neurosciences, a medical technology company specialising in dementia detection. He notes that the initial decision to refer a patient to a specialist is based on a GP’s subjective assessment of a person’s symptoms. This means that a large number of referrals end up involving the “worried well” who have “seen a movie or read a newspaper article about dementia and have convinced themselves that they have the disease”. Visiting a specialist can be expensive for reassurance, with a full range of cognitive tests typically costing the NHS around £2,000 a time.

Even these tests aren’t always accurate, resulting in people who don’t have Alzheimer’s being referred for scans, and people who do have the condition being told that they have nothing to worry about. In order to address this problem, Cognetivity has developed a series of visual tests, which Habibi says can last just five minutes, can be administered by non-medical professionals and have around a 95% accuracy, greater than existing tests such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Its system has already been approved by several NHS trusts for use in deciding which patients are given a full scale magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Mass screening could slow onset

The immediate goal of automated tests is to save health systems money by acting as gatekeeper separating those who are worrying unnecessarily from those genuinely in need of treatment. But in the medium terms, such processes could be used to screen for those suffering from early stages of the disease.

One of the unique features of Alzheimer’s is that by the time symptoms start to appear “the disease has progressed for 15 to 20 years, and a lot of brain damage has already taken place”, says Mark Edwards of ViewMind, another dementia-detection technology firm. However, there is a lot of evidence that even simple lifestyle changes in the earliest stages, such as adopting a better diet and being more active, can help slow the onset. While mass screening of patients is currently impractical, Edwards believes that ViewMind’s system, which uses a virtual reality headset to measure the brain’s ability to process visual information, could be used to predict those patients who are starting to deteriorate, decades before the disease progresses to the point where they are experiencing symptoms.

Genetic screening could also play a key role in determining who is going to be at risk of developing the full-blown version of the disease in the future, says Patrick Short of Sano Genetics, a genetic data-sharing platform. While “tens to hundreds of genes” may help determine a person’s chances of getting Alzheimer’s, the one that has a “particularly strong link” is the APOE gene that controls production of a protein called apolipoprotein E. One allele (variant) of this gene called APOE4 is found in only 25% of people, but is present in the majority of Alzheimer’s patients. Only 2%-3% of people have two copies of APOE4, but this rises to 15% among those with Alzheimer’s.

Encouraging investment in new drugs

Of course even the best diagnostic systems are going to be of limited use unless better ways to treat the disease are developed. Until recently, drug companies have been traditionally reluctant to invest money in this area, and even today “the amount of research and development in this area isn’t as much as in other areas, such as oncology”, says Parkwalk’s Doherty. Not only are clinical trials in this area expensive, but “getting good clinical outcomes” from such trials “has proved to be difficult”. The scale of the challenge is shown by the fact that as many as 300 clinical programmes have ended in failure in recent years.

The failure of so many trials means that “more work needs to be done” to further our understanding of the condition, says Doherty. However, the prospect of growing numbers of Alzheimer’s patients putting pressure on healthcare systems is encouraging governments around the world to invest large sums of money into all levels of research. The UK government has been at the forefront of this, with the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research making research into Alzheimer’s and dementia a priority. British universities, especially Oxford and Cambridge, are already starting to produce a lot of interesting discoveries.

While most drug trials have ended in failure, a few have managed to show enough promise to justify further investigation, says Doherty. At the moment there are around 18 drug trials that have progressed into phase III (the stage of the process that tests effectiveness in a large number of human patients) and 36 that are in phase II (which tests efficacy in a smaller number of patients). While there is no guarantee that any of these drugs will end up being approved, she is confident that significant progress is on the horizon.

Meanwhile, with billions available to those who are able bring a drug to market, pharmaceutical drug companies at now starting to realise that, despite the high cost of trials, “they can’t afford to neglect the area”, say Alzheon’s Tolar. This is leading them to get back into the area by investing large sums, in an attempt to find a decisive breakthrough that will help them deliver a blockbuster drug. Like Doherty, Tolar is confident that all this increased interest means that “we are likely to see several approved treatments for the disease on the market within the next few years”.

The leading contenders

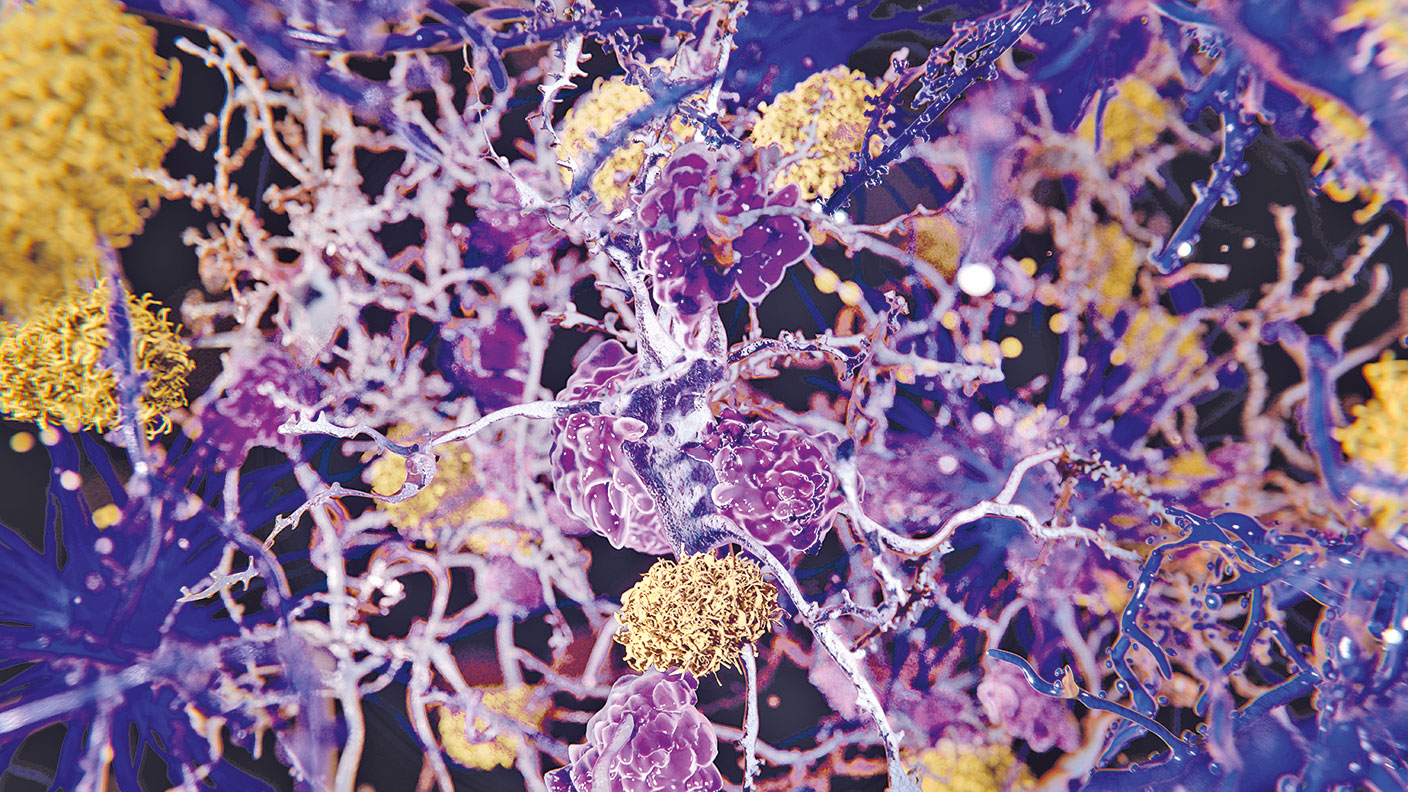

The three main drugs that are attracting attention at present are Biogen’s aducanumab, Eli Lilly’s donanemab and Alzheon’s ALZ-801. All three work – in different ways – on the theory that Alzheimer’s is caused by a corrupted form of the amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP). This protein is thought to help the brain repair itself, but researchers believe that when APP breaks down and accumulates into amyloid plaques, it becomes toxic and damages the same cells that it is supposed to defend. When damage reaches a critical level, people start to suffer symptoms.

Of the three, the closest to making to market is aducanumab, which could be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as early as next month. If so, it would be the first approval in this area since 2003. However, while trials suggest that there is statistically significant evidence that the drug slows the progression of the disease in its later stages, the effect is relatively small. Indeed, with the FDA’s own advisory panel recommending against approving the drug, experts estimate that the chance of getting the green light is only around 50%.

There’s also the added complication that, since amyloid plays a vital role in “protecting the brain against injury or infection”, reducing the levels of healthy amyloid “can have big negative implications” for general health, says Tolar. Both aducanumab and donanemab have been linked to an increased risk of brain oedema (swelling due to trapped fluid). As a result, even if the FDA approves aducanumab, rival companies are still likely to continue working on their own treatments, in the hope that these could be more effective. For example, Tolar obviously hopes that Alzheon’s drug ALZ-801 – which he believes could be approved by 2024, or even earlier if the FDA decides to speed up the process – could end up being the dominant treatment. He argues that existing trials have shown that it is much more effective than its competitors; that it has been associated with fewer side effects; and the fact that it is delivered through a twice-daily pill, as opposed to intravenous (IV) infusion, makes it more convenient for elderly patients.

Future treatments with gene therapy

Using drugs to target rogue amyloids, as well as tau proteins, another group of neural proteins that has been linked to both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, is the most popular approach at the moment, but there’s also been an increasing amount of interest in gene therapy. For example, the key to fighting Alzheimer’s could be through a protein known as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), thinks Mark Tuszynski, professor of neuroscience at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. Since Alzheimer’s patients tend to have lower levels of this protein, which helps rebuild brain synapses, he hopes that increasing the level of BDNF in the brain can not only slow the progress of the disease, “but also rebuild connections between parts of the brain” to improve the memory of sufferers.

However, getting BDNF into the brain is not easy. It isn’t absorbed by the gut, so it can’t be delivered by a pill, and it’s blocked by the blood/brain barrier, so IV infusion is unlikely to work. Tuszynski’s idea is to inject a modified virus carrying the gene into the brain, which will prompt nearby cells to start producing BDNF. Preliminary results from animal studies suggest that the boost from a one-off treatment could last for up to nine years, and have prompted his institute to set up a human trial of the technique. If everything goes to plan, this could be available as a treatment option within the next five years.

Meanwhile, researchers at Cornell University are targeting the APOE4 allele, which has been linked to both an increased likelihood of getting Alzheimer’s as well as an earlier onset of the disease. They have begun a trial that floods the brain with a different allele, APOE2, which has been associated with a reduced risk of getting Alzheimer’s.

However, commercial use of gene therapies for the disease probably lie further in the future. We look at some firms with more immediate prospects below.

The leading contenders in Alzheimer’s drugs

Among the larger biotechnology and pharmaceutical firms, Biogen (Nasdaq: BIIB) stands out for putting a lot of resources into finding an effective treatment for Alzheimer’s. Even if the FDA’s decision on whether to approve aducanumab, which is due in June, ends up going against it, Biogen has four other Alzheimer’s treatments undergoing clinical trials. These include BAN2401, which is in phase III, and gosuranemab (phase II), while BIIB076 and BIIB080 are in phase I (safety) trials. The downside risk is limited by the fact that Biogen already has several successful drugs on the market and trades at only 14 times forecast 2022 earnings.

Eli Lilly (NYSE: LLY) is also at the forefront of the race to develop new Alzheimer’s drugs, with early trial data suggesting that its donanemab drug slows the progression of the disease. The firm is currently running multiple phase III studies for use in Alzheimer’s patients at different stages of the disease, including pre-symptomatic patients. While the stock trades at a more expensive 23 times forecast 2022 earnings, this is more than justified by the fact that revenue has increased by more than 150% over the last three years.

Alzheon, which is developing ALZ-801, is not listed (it has twice pulled a planned initial public offering), but there are a number of smaller biotech firms working in this area. Alector (Nasdaq: ALEC), which specialises in neurology, has several Alzheimer’s drugs in its pipeline, including AL002, which has reached phase II clinical trials. Its portfolio also includes other interesting prospects, such as AL001, which is in the final stage of trials to see whether it can help with frontotemporal dementia. Alector is partnering with pharma giant AbbVie (NYSE: ABBV), which is obviously not a pure play on Alzheimer’s, but looks cheap at just 8.4 times forecast 2022 earnings.

Denali Therapeutics (Nasdaq: DNLI) is also focused on neurological diseases. This is one to watch, with a pipeline targeting diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, say Julia Angeles, Rose Nguyen and Marina Record of the Baillie Gifford Health Innovation Fund. Denali’s most promising Alzheimer’s treatment is DNL788, which has started phase I trials in partnership with Sanofi. The firm isn’t making any money, but has enough cash to support development of its main drugs.

Loss-making Axsome Therapeutics (Nasdaq: AXSM) looks riskier, but has a combination drug therapy, AXS-05, in phase III trials for reducing agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s (something that no drug is currently able to do). While this is palliative – it reduces symptoms rather than slowing the course of the disease – the ability to improve patients’ quality of life means that sales could be as much as $3bn a year if the drug is approved. The FDA has granted it Breakthrough Therapy designation, meaning it will be eligible for an expedited decision after trials conclude.

SEE ALSO

Make uncommon profits from helping cure rare diseases

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries

8 of the best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleriesThe best properties for sale with minstrels’ galleries – from a 15th-century house in Kent, to a four-storey house in Hampstead, comprising part of a converted, Grade II-listed former library

-

The rare books which are selling for thousands

The rare books which are selling for thousandsRare books have been given a boost by the film Wuthering Heights. So how much are they really selling for?

-

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brands

How to invest as the shine wears off consumer brandsConsumer brands no longer impress with their labels. Customers just want what works at a bargain price. That’s a problem for the industry giants, says Jamie Ward

-

A niche way to diversify your exposure to the AI boom

A niche way to diversify your exposure to the AI boomThe AI boom is still dominating markets, but specialist strategies can help diversify your risks

-

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economy

New PM Sanae Takaichi has a mandate and a plan to boost Japan's economyOpinion Markets applauded new prime minister Sanae Takaichi’s victory – and Japan's economy and stockmarket have further to climb, says Merryn Somerset Webb

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom