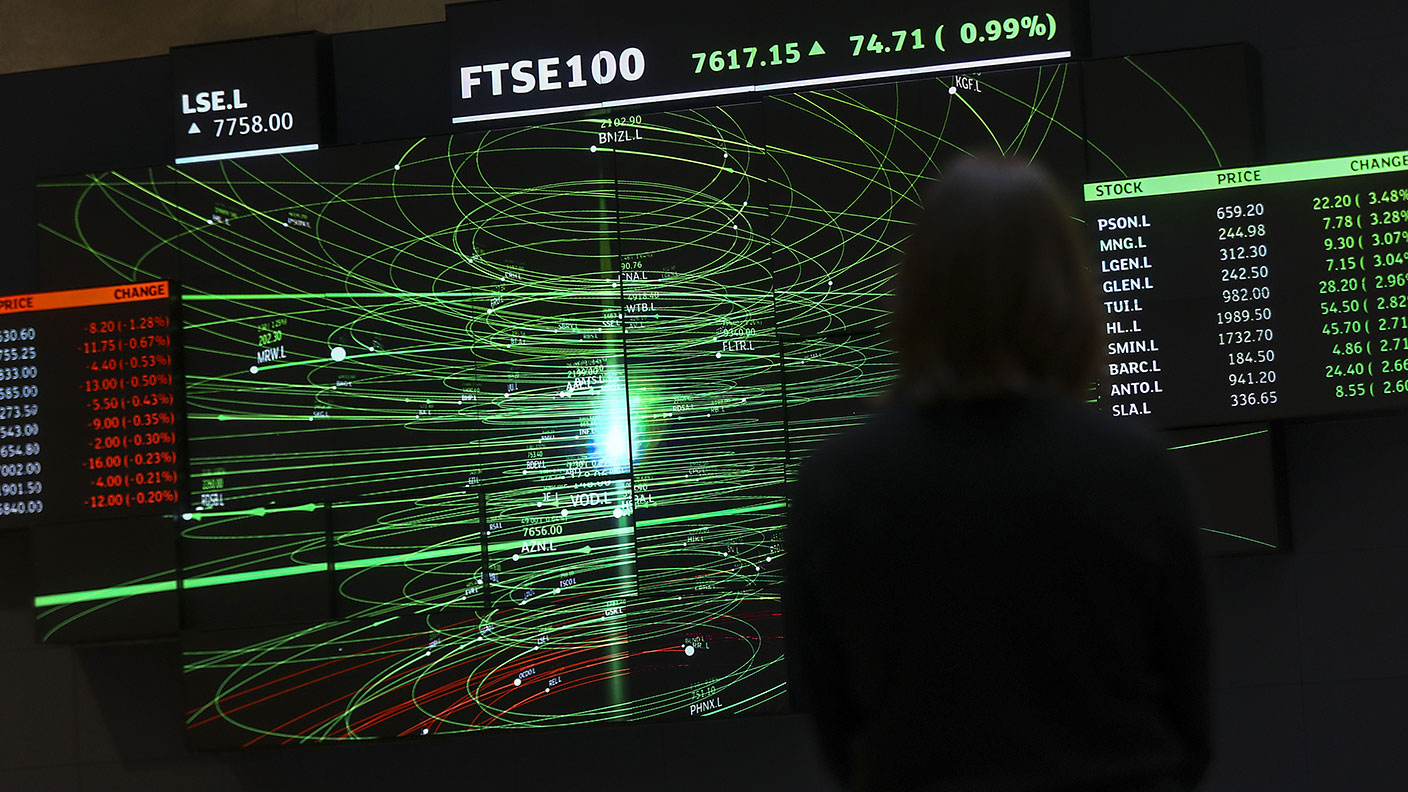

UK stocks should cope with rising interest rates better than other markets

Central banks are turning hawkish and raising interest rates. John Stepek looks at what that means for both long duration and short duration assets.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

We've regularly discussed the notion of long duration and short duration assets here.

To cut a long story short, "duration" is a measure of sensitivity to interest rate changes.

The longer an asset's duration, the more it'll move when rates go up or down.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Long duration assets have had a great run, as interest rates have been falling relentlessly for years.

But now that's stopped. So what should you invest in instead?

Why long duration assets have done so well

Duration is all about the value of future cash flows. Say you are offered the promise of a guaranteed payout of £10,000 in 10 years' time. How much money are you willing to pay for that promise today?

The answer is: it depends. But if interest rates are 1% today, you'll be willing to pay more than if interest rates are at 10% (for ease of use, we'll ignore inflation as that complicates things). You'll also be willing to pay more in an environment where rates are expected to fall, compared to one in which rates are expected to rise.

Now what would you pay for a guaranteed payout of £10,000 in a year's time? Again, you'll be willing to pay more if rates are at 1% than if they are at 10%. But the difference between those two sums won't be particularly big.

In other words, the value of £10,000 in a decade's time is far more sensitive to changes in interest rate assumptions than the value of £10,000 in a year's time.

So a "long duration" asset is one where the payoff is far away, and a "short duration" asset is one where the payoff is nearby. That's why I sometimes call it a "jam tomorrow" asset.

"Long duration" assets have done really well in recent decades because interest rates have just kept on falling. Now though, interest rates are flipping around and there's a glimmer of suspicion that this might be the end of the secular (ie long-term) trend that saw them fall relentlessly since the 1980s.

That means "short duration" assets are starting to look more appealing. So what does that mean for investors?

How to position for a shorter duration world

Well there's an interesting piece of research highlighted by Joachim Klement in his most recent blog. The research is by Jules van Binsbergen of Wharton business school at the University of Pennsylvania.

Binsbergen's body of research compares long-term returns on bonds with those on shares. It treats shares as long-duration assets and compares their performance with long-duration bonds.

I won't go into the details because it gets quite dense. But in effect, what Binsbergen finds is that if you invest in bonds that have the same duration as equities, the bonds give you the same return but with less volatility.

This research, as Klement points out, raises a few tricky questions. The most obvious conundrum is this one: shares are riskier than bonds. If you lend your money to a developed world government – and certainly to the US – you can feel as sure as you can about anything in markets that you'll get paid the interest and your money back at the end of the term.

The only real risk is the big picture backdrop: what happens to interest rates? What happens to inflation? And all the rest of it.

Shares, on the other hand, carry loads of risk by comparison. Companies are under no obligation to pay dividends. Earnings are subject to the vagaries of the economic cycle, but they're also subject to the vagaries of consumer taste and competition and technological development. They are obviously much riskier than bonds – there is no debate about that.

If an asset carries more risk, then economic theory states that it should deliver greater returns. Why would you take the risk of investing in shares if you could get exactly the same return in bonds?

So it's a bit of a shocker to find that investing in equivalent bonds would have given you a better risk-adjusted return.

Anyway, that's a quandary for another day. What's also interesting about the research is that in a follow-up study, Binsbergen expanded his research beyond the US and into other developed markets. He found the same thing – that equivalent bonds would, in effect, beat equities.

But he also found that different equity markets had different durations. Between the US, Japan, the eurozone and the UK, the US – as measured by the S&P 500 – has the longest duration. That makes complete sense. The US has massively outperformed every other market in recent years and it's also the one with all the hot-but-not-yet-profitable "jam tomorrow" stocks.

What's the one with the lowest (or shortest) duration? You guessed it. The FTSE All-Share.

So if you're looking to adjust your equity asset allocation to cope with a brave new world in which rising interest rates mean shorter-duration assets have their time in the sun, then the solution is straightforward: reduce your US exposure and increase your UK exposure. Which is, of course, pretty much what we've been suggesting you do for a while now.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.