What the end of the 1970s bear market can teach today’s investors

The 1970s saw the worst bear market Britain has ever seen, with stocks tumbling 70%. Things have changed a lot since then, says Max King. But there are five important lessons that today’s investors should learn.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

What triggers the end of a bear market? With the benefit of hindsight, it always seems obvious but, at the time, much less so.

The analogy between the present time and the inflationary 1970s makes the lessons from them highly relevant, particularly as it has disappeared from folk memory.

How the 1970s bear market ended

6 January 1975 marked the day when the worst bear market the UK has ever seen ended. From its peak in 1972, the market had fallen 70% in actual terms, and 80% adjusted for inflation.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Half of all stockbrokers had lost their jobs, and being a partner in those days meant not drawing a salary, but writing a cheque each month to keep the firm afloat.

The cause of the bear market was no mystery: inflation had been rising steadily for ten years, but in 1973, it accelerated, ending 1974 at 19%. The oil price quadrupled, as a result of the Arab oil embargo that followed their defeat by Israel in the Yom Kippur war. Almost all other commodity prices multiplied too.

Inflation was a global phenomenon, but Britain proved to be exceptionally vulnerable. Long-term economic performance had been poor, expectations (as always) ran well ahead of the nation’s capacity to create wealth, and a highly unionised workforce was able to force up wages in line with prices, resulting in an inflationary spiral.

Shareholders weren’t the only ones to suffer. Bond yields, already 8.3% by the end of 1971, rose to 17%, resulting in a “real” (after-inflation) loss on gilts of 48%, while even cash lost 9% in real terms. Both these figures ignore income tax at a rate of up to 98% for private investors.

There was no escape. Although in the US, the S&P index fell “only” 42% (rather less in sterling terms) and US bond yields reached just 7.4%, exchange controls meant that overseas markets were closed to domestic investors unless they were prepared to pay an exorbitant premium of up to 60% on an officially sanctioned black market.

There were few winners. Stockjobbers Ackroyd & Smithers, later to become the market-making arm of Warburgs, made large profits shorting shares and bonds all the way down.

The Labour government, which had scraped a tiny overall majority in the election of October 1974, was able to nationalise at knock-down prices, including taking majority control of BP by buying a further 25% from Burmah when it ran into financial difficulties.

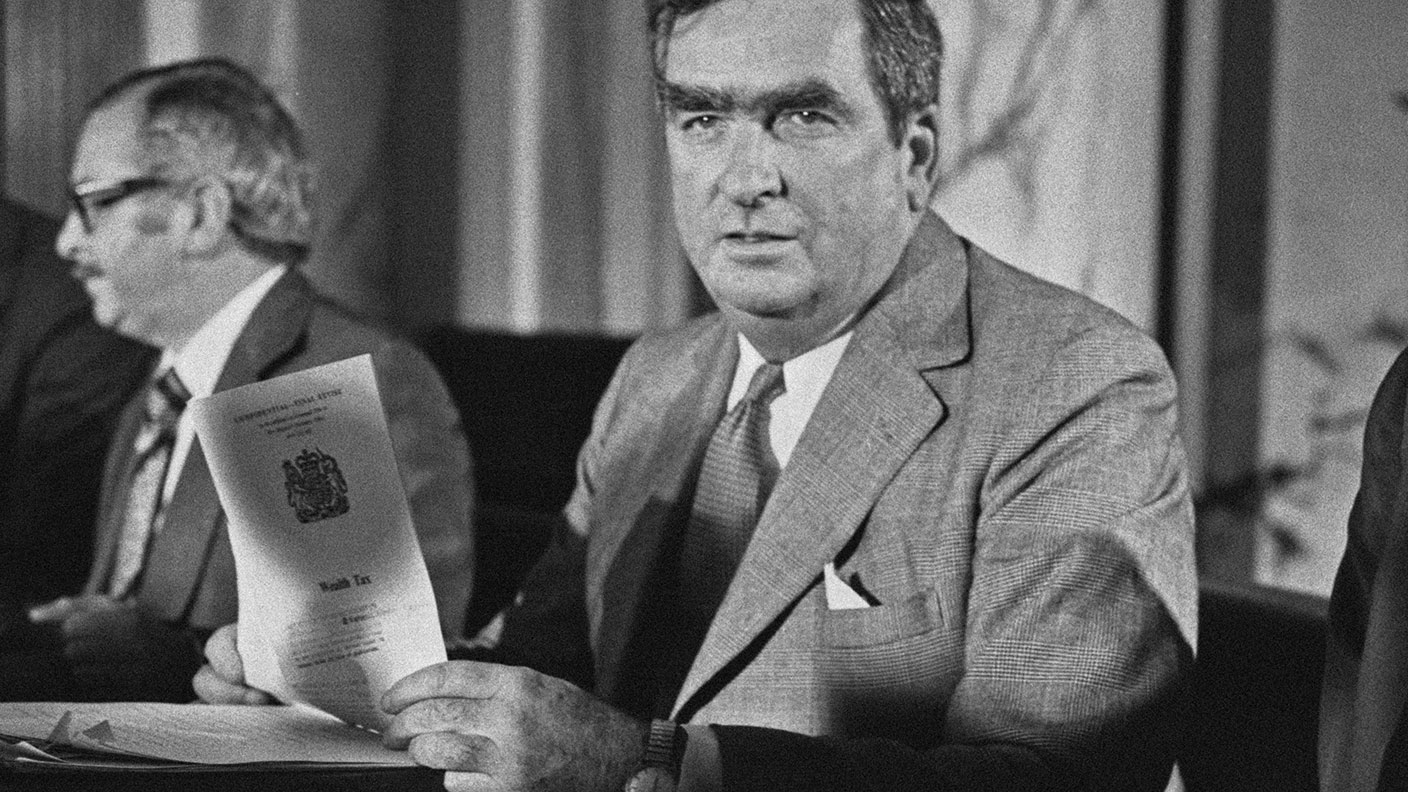

Labour’s chancellor, Denis Healey, had vowed to tax the well-off “until the pips squeaked,” but instead secured the long-term future of the Channel Islands as an offshore financial centre.

When the market turned, it did so dramatically, rising up to 15% in a day and doubling in a matter of weeks. Since all the jobbers were short, they simply widened their spreads to dissuade buyers, and investors had no chance to get aboard. Only those who had bought on the way down, when the market seemed to be heading for oblivion, profited from the recovery.

A long, slow slog back to bull market territory

The turning point gave rise to a variety of myths. It was claimed that a group of major institutions, with Bank of England approval, had acted in concert to rescue the market, but no evidence was ever produced that they invested significant sums.

The hindsight traders always maintained that the market was blindingly, obviously cheap, yielding 11% and on a price/earnings ratio of about six, but pessimism was so extreme that investors just couldn’t see it.

It was never that easy. Inflation went on rising, reaching a peak of 30% in 1975, and the economy went into recession. Inflation destroyed cash flow, and after adjusting falling profits for the effect of inflation on the replacement cost of fixed assets, stock values and working capital, profits disappeared, the p/e was infinite and the dividends unaffordable.

After doubling, the market indices made no progress in real terms for another seven years. Bond yields fell to 14% in 1975, returning 10% in real terms, but gave a zero total return in real terms over the next six years.

The real bull market didn’t start until 1980, when both bond and equity investors came to realise that the new, business and investor-friendly government really was determined to squeeze inflation out of the system, and that policy makers in the US and Europe were doing the same. In the next 20 years, the UK market indices trebled relative to nominal GDP, but remained well below the lowest level of the 1960s.

It seemed that UK investors would never be faced with such a nightmare again. The UK market became far more international and less dependent on the domestic economy than ever before. Globalisation and the collapse of communism brought more freedom of movement of people, capital, companies and savings, with disinflationary and wealth-creating consequences.

This, and memories of the 1970s, seemed to make a significant rise in inflation unlikely.

Still, there has been back-sliding on globalisation, repression has returned to significant areas of the world, Western governments have become complacent about deficit spending, and central bankers believed that they could print money without consequences.

Hopefully, the cost of the back-sliding is now evident and can be reversed without more than a scare as opposed to the 1970s nightmare of embedded inflation.

Five lessons from the 1970s for today’s investors

For investors, there are important lessons. Firstly, equities are not “a good hedge against inflation,” as popular wisdom claims. Quite the reverse; the prospect of lower inflation is a wonderful tonic. If investors believe that central banks are determined to fight inflation, bond yields will stabilise, then start to fall.

This is much more important for equities than the trend of earnings. Turning points are often marked by recessions in which corporate earnings are falling but investors look ahead to the return of economic growth and the rebound in earnings that will bring. Jerome Powell, chair of the US Federal Reserve, appears to understand the importance of quashing inflation, but Andrew Bailey at the Bank of England doesn’t.

Secondly, turning points in markets are not visible in advance. Don’t wait for a clear peak in interest rates or inflation to be visible. Markets turn when marginally more investors decide that things will get better than will get worse.

Thirdly, this can easily turn into a stampede so buying on the way up is not an easy decision. Markets always stay ahead of the fundamentals and there is no certainty that the trend is now upwards rather than just a rally in a bear market.

Fourthly, the bears never change their mind. For them, the market recovery is always premature or ahead of events and valuations are too expensive.

Finally, remember the maxim that “those who forget the lessons of history are condemned to repeat them.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.