Don't fight the Fed – at least, not yet

The US central bank has made it clear it will keep propping markets – at least until inflation takes off. Betting against it would be a bad idea. But, says John Stepek, don’t make the mistake of thinking the Fed is an all-powerful master of the markets.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

There were no fireworks at the latest Federal Reserve monetary policy meeting.

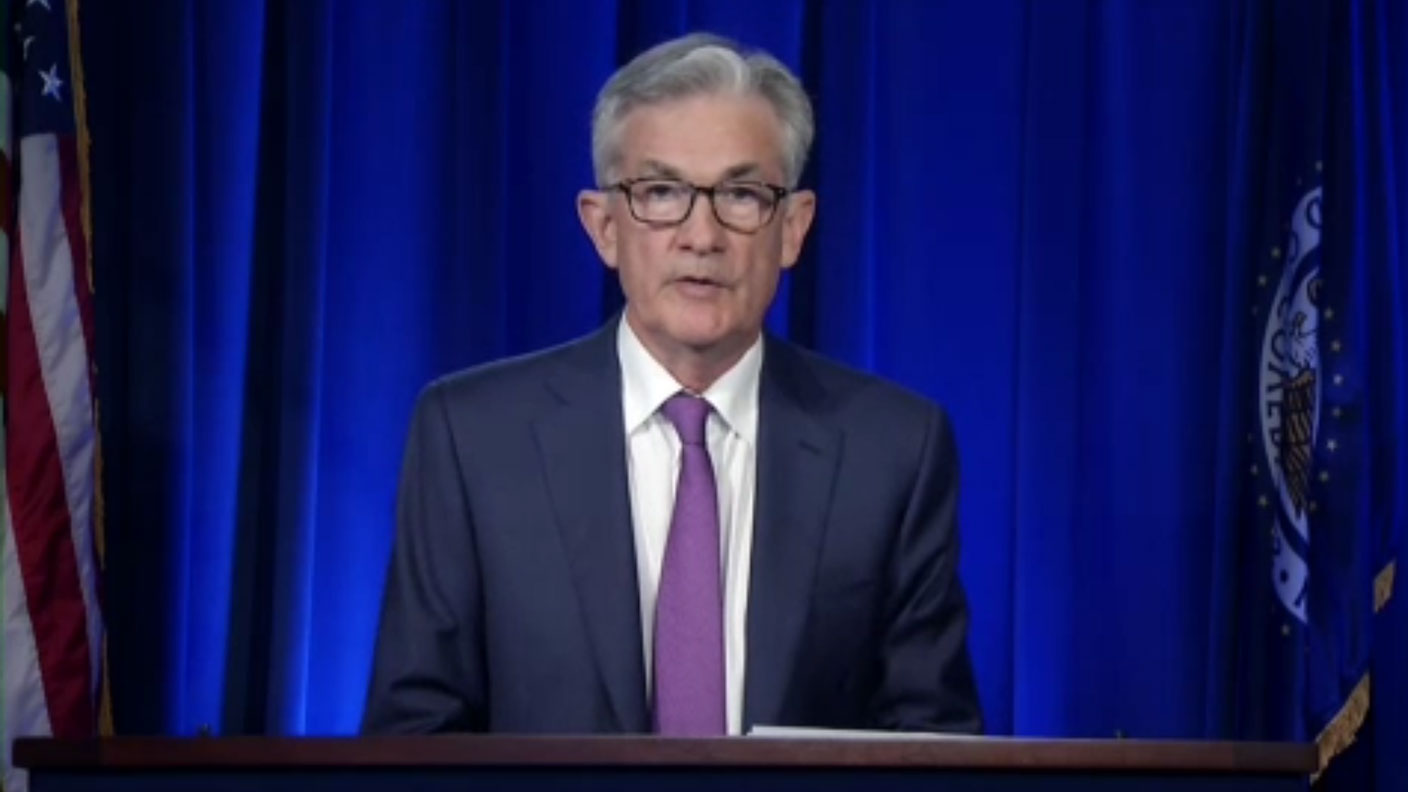

But in case you were in any doubt, Fed chief Jerome Powell made it very clear last night that higher interest rates are not even close to thinking about dreaming of drifting onto the horizon of the US central bank’s long-distance radar.

No rate rises. Ongoing cheap money.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

They say: “Don’t fight the Fed” – and who are we to disagree?

Inflation is the one thing that can derail central bank support for markets

“We’re not even thinking about raising rates,” said Federal Reserve chief Jerome Powell last night. He justified this by arguing that the coronavirus is “a disinflationary shock… we see core inflation dropping to 1%. I do think for quite some time, we’re going to be struggling against disinflationary pressures."

Now we can debate the latter point, but the big takeaway here for investors is that the Fed is not going to be getting worried about inflation, and certainly not about rising asset prices, any time soon.

The old market saying is: “Don’t fight the Fed”. How true is it? Much as I hate to say it, the saying has held a lot of water in the last few decades.

Central banks can't prevent a big bear market from happening, as we’ve seen in the past. But what has happened is that they’ve grown increasingly willing to step in to underpin the financial system as soon as there’s any sign of stress.

That in turn has meant that rallies following collapses in the market have become ever more rapid. The most recent coronavirus one was the quickest on record. On the one hand, you can argue that the coronavirus shock is unique, and it is. But on the other hand, so was the enormity of the Fed’s response.

The closest we've come to a more traditional bear market (in the US, at least) in the last ten years was when the Fed decided that it would start raising interest rates when Powell first took the role in 2018. That was brought to an end pretty sharpish, primarily because markets threw a hissy fit.

In short, it took Powell a while to realise that his job is mostly about propping up the S&P 500 – and thus for markets to trust him – but he got the message eventually.

So if the Fed is on board with keeping monetary policy loose, then history suggests that betting on collapsing markets is a losing game. The truth is that central banks have proved that they can prop up asset prices, even in the face of disinflation or deflation.

The usual “but what about Japan?” question doesn’t even apply here. The Japanese central bank may have been unable to spark consumer price inflation, but since it took the gloves off under Shinzo Abe, the Japanese stockmarket has done perfectly respectably.

As I’ve said many times before, the only thing that can really put a spoke in the wheels of this market is a proper rip higher in inflation. That would be a problem, because central banks can’t tackle inflation with loose monetary policy. Once inflation gets going, you either let it go higher, or you tighten up.

However, central banks want inflation to rise. You can safely assume that the global inflation target of central banks is no longer 2%. They’d like inflation to be higher. They need inflation to be higher.

So they will let it go up. In turn, that means you don’t have to worry about central banks tightening up until inflation is already a problem. At that point, it’ll probably be apparent in wider markets in any case.

Don’t mistake an infinite supply of funds for economic mastery

Can central banks get inflation to go up? That’s the wrong question.

I agree that “don’t fight the Fed” is good investment advice. However, don’t mistake that for omnipotence. The economy is not a machine, and the Fed is not a genius engineer, tinkering with said machine.

“Don’t fight the Fed” is good advice simply because a determined, price-insensitive buyer with an infinite sum of money is always going to trump the fundamentals, regardless of how bad you might think they are. A refusal to accept that is just stubbornness.

As far as inflation goes, I’ve already discussed a lot of reasons why I think it could and should go up. And a lot of smart people who have been deflationists during the last decade (correctly) are now changing their tunes. That seems worth watching.

However, as far as your investments go, you don’t really need to worry about exactly when inflation will take off. As of right now, it’s not here. So be prepared for it (own some gold – which will no doubt have a wobble as it’s been overbought, but don’t stress about that).

But also be aware that it’s fine to keep holding equities and sticking to your long-term plan. It seems unlikely that a fresh crash is around the corner.

Central banks are making it clear that they’ll step in where market stress looks like it’s getting out of hand. Governments are clearly a bit nervy about the amount of money they’re spending, but we’re also in a new era where austerity is very much a dirty word. So when push comes to shove, the purse will come out.

And there are plenty of appealing prospects out there, whether you like sectors and themes, or individual stocks. We not only look at gold and silver (of course) in the next issue of MoneyWeek (out tomorrow) – but we also look at fintech and commercial property funds, just to pick a few of our features. If you’re not already a subscriber, sign up now and get your first six issues free.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?

What's behind the big shift in Japanese government bonds?Rising long-term Japanese government bond yields point to growing nervousness about the future – and not just inflation

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.