What can the 1957 stockmarket crash teach us about the coronavirus crisis?

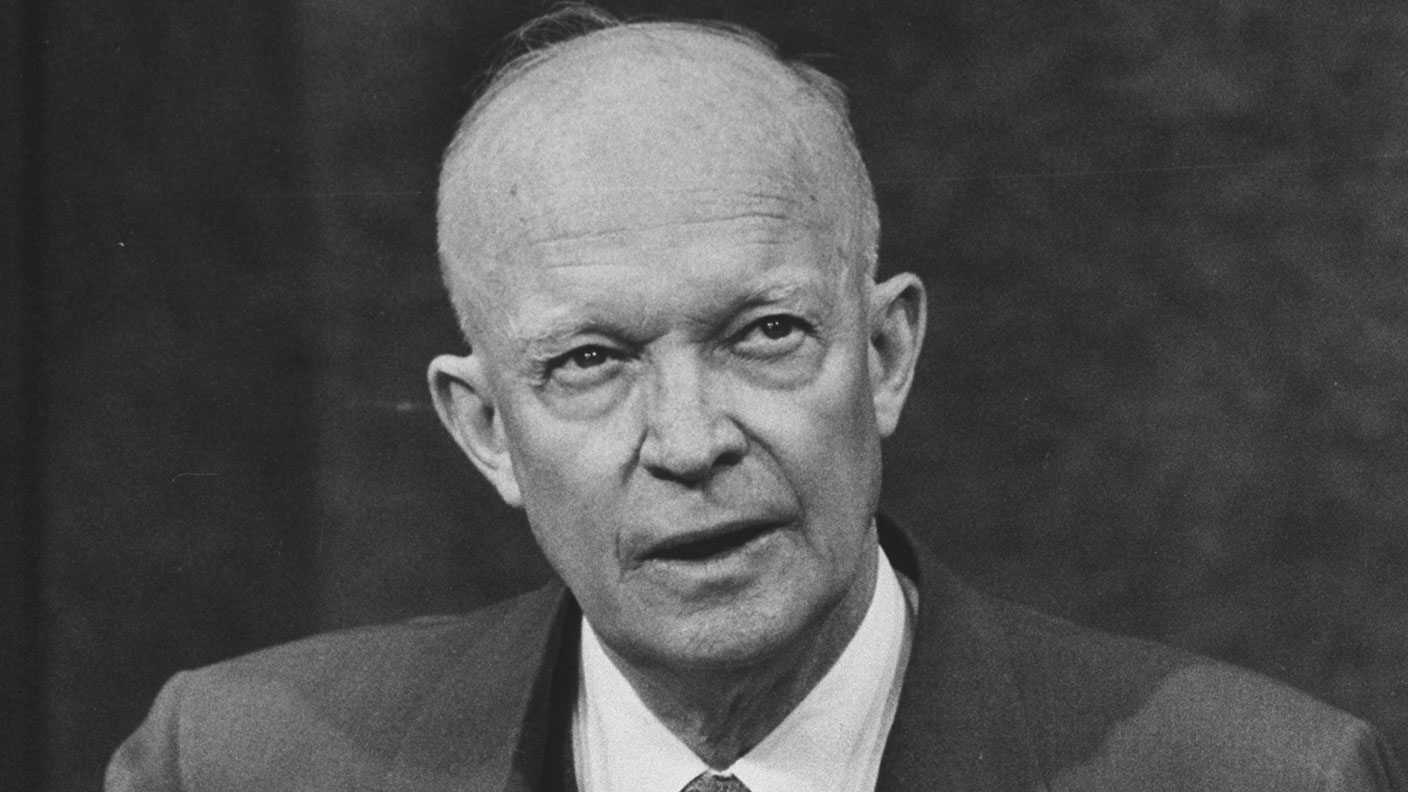

In the "Eisenhower Recession" of 1957, the stockmarket crashed, unemployment soared – and a flu epidemic ravaged the globe. John Stepek looks at what we can learn from it today.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Today we’ll take a break from the usual charts of the week. Instead, to celebrate the publication of MoneyWeek’s Little Book of Big Crashes (free if you subscribe to MoneyWeek today – and you get your first six issues free too), I wanted to talk about a little-known recession and market crash that has surprising significance for the present day.

From the summer of 1957 to the spring of 1958, the US had a recession. It was also known as the Eisenhower Recession, after the sitting US president of the day.

You almost certainly haven’t heard of it (particularly if, like most of our readers, you’re living in the UK). Yet it was pretty big. In fact it was the worst recession of the post-war period, right up until the 1970s.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

So what on earth happened in 1958 that was so dramatic? And why talk about it now?

The Eisenhower recession – the steepest downturn you’ve never heard of

The Eisenhower Recession lasted from August 1957, and it ended in April 1958.

The S&P 500 had, coincidentally, launched in 1957. It peaked in June 1957 at just over 49 points, then fell by nearly 21% until it hit a trough in October of the same year, at just under 39 points.

For what it’s worth by the way, the stockmarket at that point was a bit more expensive than the long-run average (using the cyclically-adjusted price/earnings ratio) but it wasn’t ridiculously expensive (nothing like the S&P 500 was before the present crash, for example).

Meanwhile, on the economic front, unemployment rose from 4.1% in August 1957 to a peak of around 7.5% by the summer of 1958, before heading back down to around 5% by mid-1959.

This might not sound all that remarkable. And it was pretty short-lived. And yet the ferocity of the downturn was striking.

The first quarter of 1958 saw US GDP shrink by 2.6%, notes Deutsche Bank in a survey of “large economic contractions” of the last 800 years. That makes it the second-worst quarter-on-quarter slump in output since 1947.

That includes any quarter during the great financial crisis, including the fourth quarter of 2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed. (The worst, unfortunately, is expected to be the second quarter of this year – Deutsche Bank reckons that GDP will contract by 9.5% compared to last quarter).

And yet for 1958 as a whole, as Alex Tabarrok notes on the Marginal Revolution blog, GDP declined by less than 1% because growth rebounded vigorously in the second half of the year.

So what happened? The argument goes that the problem was mainly down to tighter monetary policy. The Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, was raising interest rates in order to tackle rising inflation (indeed in August 1957, the month the recession – with hindsight – started, the Fed had raised rates by half a percentage point to 3.5%, and didn’t cut again until December that year).

That seems to make sense. A recession is usually driven by tighter monetary policy coming and hitting an overstretched economy that has taken on too much debt of one sort or another.

And yet, does that entirely explain the scale of the slump and the speed of the comeback? Maybe – maybe not.

The flu pandemic of 1957

You see, something else happened during this time. A flu pandemic. An outbreak of the H2N2 strain emerged in East Asia in spring 1957. It was reported in Singapore, then Hong Kong, and started to make itself known in the US by summer 1957. There was then something of a "second wave” in spring 1958, when mortality spiked again.

For context, it’s viewed as less severe than either the 1918 pandemic or the one that erupted in 1968. Even so, that flu is estimated to have killed in the region of 70,000 to 100,000 people in the US and more than a million worldwide (perhaps up to two million depending on who you read, which shows how difficult getting reliable death rates for these things is, even well after the fact). As many as 14,000 died in the UK.

In passing, it’s interesting to note that, as with the present day, all the usual concerns of the time were imposed on the story. For example, according to the Washington Post, people wondered if the flu strain was a mutation caused by nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific (shades of “nature taking its revenge”), or if it had been planted by Communists (was it grown in a biolab?).

Now most of the research I’ve looked at for this piece implies that the flu pandemic was coincidental with the recession rather than causing it. I think that’s probably fair enough (there are always background problems, just as there are today.

But the idea that it had no effect at all seems far-fetched. For example, car sales in particular dropped dramatically. In 1955, eight million vehicles were sold in the US (a peak that wouldn’t be seen again until the early 1960s). In 1958, just 4.3 million were sold. And consumer spending turned negative during the first quarter of 1958, which is a vanishingly rare occurrence.

And while schools and businesses generally were not officially shut down, it was extremely disruptive. Lots of people caught it, lots of people were off work or off school – it’s a valuable reminder that keeping the economy open doesn’t necessarily make a big difference if no one is well enough to actually do their job.

So while I’m open to the idea that the recession would have happened anyway, it seems a stretch to divorce the rapid, short-term severity of this one from the fact that large chunks of the population were ill or worried about getting ill (at a time when the welfare state was a lot less developed) during this period.

So what might it all mean for today? Clearly, the current situation is much worse than 1957, both in terms of the Covid-19 virus itself (it’s more lethal, or certainly appears to be) and our reaction to it (a near-total shutdown).

But it also suggests that, as and when the flu passes, a rapid rebound in activity remains possible. And you also have to remember that while the economic slump is worse, the authorities’ reaction to it – spend as much money as it takes and prop up every business going where possible – has also been much more radical.

Don’t be surprised if the biggest overall effect of this slump – economically speaking – arises more from the fallout from our reaction to it, than from the event itself.

For more on historical crashes and their lessons for today, you can get an electronic copy of my latest book, MoneyWeek’s Little Book of Big Crashes, absolutely free when you subscribe to MoneyWeek magazine. Not only that, but you’ll get your first six issues free too. Don’t miss out – subscribe now.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.