Why you should ignore the pessimists and invest now

There is widespread fear that massive fiscal stimulus will result in uncontrollable inflation. But don't worry, says Max King. Use the current market uncertainty to your advantage.

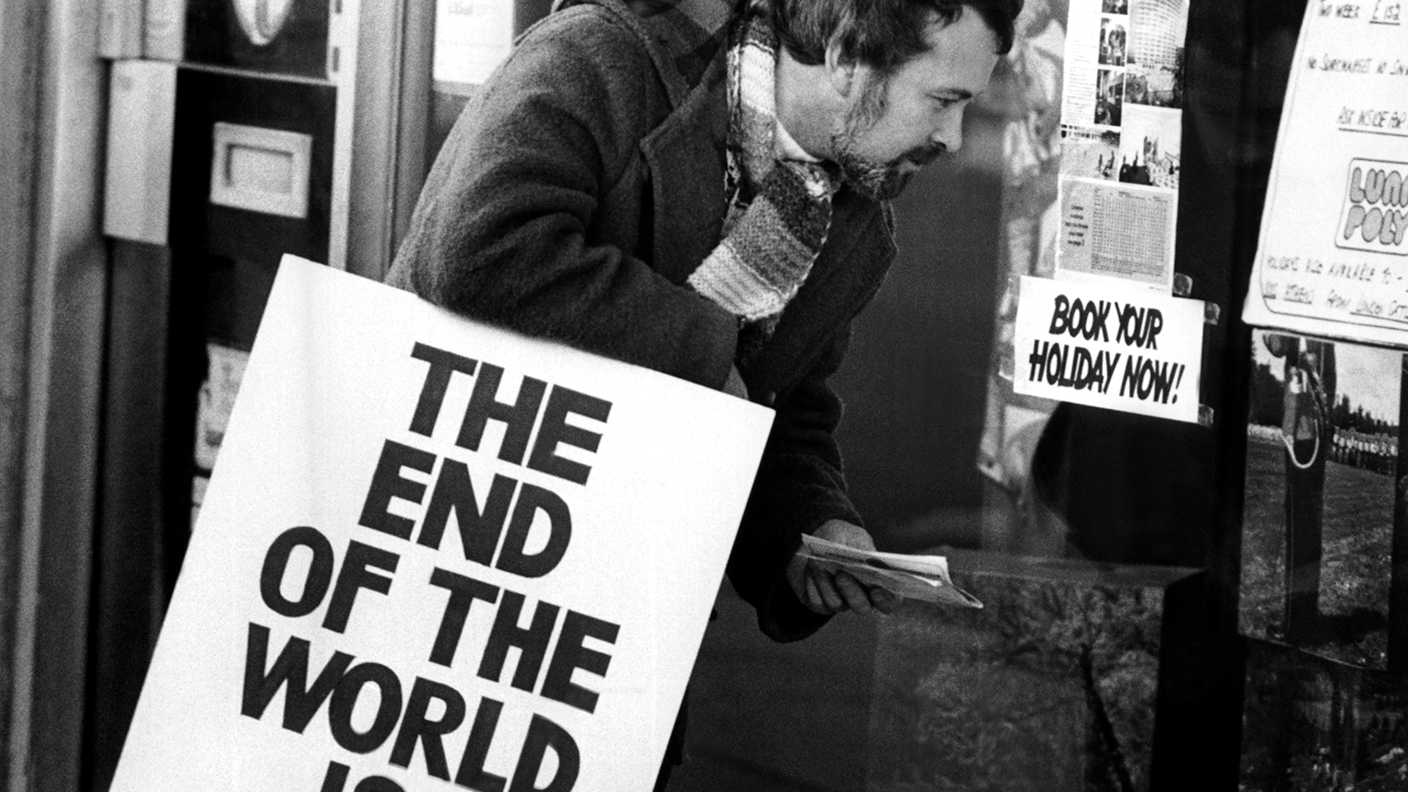

Bull markets climb a wall of worry. And there are plenty of Jeremiahs forecasting disaster for financial markets at present.

Their end-of-the world-thesis is that excess money creation – the result of a massive fiscal stimulus intended to cushion the economic, social and health consequences of the pandemic – is bound to result in escalating inflation.

Government borrowing in developed economies has soared and been financed, in effect, by printing money. Central banks buy all the debt issued by the government so the money supply balloons. Too much money chases too few goods, and inflation takes off.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

This ought to raise the cost of financing government borrowing. But governments will use “financial repression” to limit the rise in bond yields, ensuring that real returns are negative.

Thereby, they inflate away their debt, which then falls steadily relative to economic output. Government finances are saved at the expense of savers and investors, as cash balances are eroded by inflation, bond markets deflate and stockmarkets collapse. Only the gold price rises.

“We told you so”, crow the Jeremiahs.

Why you shouldn’t be overly worried about inflation

Are the Jeremiahs right?

The above is broadly what happened in the post-war decades. And the pessimists expect history to repeat itself. But those decades were marked by limits to the operation of free markets which no longer apply.

Globalisation, technological change and the resulting decline in the negotiating power of organised labour mean that the constraints to output which forced up wages, commodity prices and hence prices in general no longer apply. Now, “too much money” may just increase output and raise asset prices rather than trigger inflation.

Economic growth would result in some short-term bottlenecks, particularly in the supply of commodities, but higher prices would soon stimulate more supply. Inflation might fluctuate around 2%, as central banks intend, rather than soar.

That would justify yields on long-dated government bonds rising above 2% to perhaps 3% for 30-year debt. Provided governments don’t stifle growth through taxation, protection or heavy-handed regulation, there really could be another “Roaring Twenties.”

So far, this Panglossian thesis is working out well. It was absurd that, at the start of the year, 40% of government bonds and 10% of corporate bonds traded on negative yields. Their subsequent rise to 1.7% for 10-year US Treasuries and 2.4% for 30 years is both as expected, and healthy.

It fires a warning shot across the bows of spend-thrift governments, shatters the delusion that they can control market prices through “financial repression” and humbles over-confident central bankers. Ed Yardeni refers to it as “the return of the bond vigilantes” with bond markets forcing fiscal and monetary discipline, as they did in the 1980s. Unfortunately, the vigilantes have left it a bit late.

Congress has already passed a $1.9trn stimulus package, on top of the $900bn enacted in December. Yardeni agrees with the analysis of Larry Summers, Bill Clinton’s economic adviser. Summers pointed out that the December package alone would reduce the gap of $50bn a month between actual and potential GDP to $20bn. So a further stimulus of $150bn a month was grossly excessive, especially when US consumers were sitting on $1.5trn of surplus savings.

Moreover, Biden’s plan includes significant disincentives to work, as it provides benefits that exceed the income many people are likely to earn.

If the UK were to attempt comparable fiscal expansion financed by the Bank of England, money would flood overseas via the trade account or capital flows, and sterling would drop, causing inflation.

Global demand for dollars may mean that the US administration can get away with it but they are skating on very thin ice. Without the bond vigilantes, the coordinated recklessness of the US administration and Federal Reserve could make the Jeremiahs right after all.

At least the UK government is worrying about the build-up of its debt and recognises that bringing it down will be a long slog. The US will learn soon enough.

Don’t count growth out yet – value has had a great run but it might well stall

It’s not surprising that stockmarkets have stalled while bond yields are rising. But once yields settle, equities should move higher, pushed up by rising corporate earnings and accumulated excess savings.

The Jeremiahs worry that the low holdings of cash shown by surveys of institutional investors mean that there is little buying power. But this ignores the vast amounts sitting in savers’ bank accounts, earning next to nothing. Net retail sales of open-ended funds trebled last year to over £30bn, with money also flowing into investment trusts and the wealth managers. These flows are likely to continue.

The rise in bond yields has undermined growth stocks and given new hope to value investors, but extrapolation of this trend for the long term is dangerous. Value has already outperformed growth by around 20% since the autumn, with many of the bombed-out recovery plays multiplying in value.

These need earnings to catch up, while the shares that have been left behind are mostly of lower quality. Some of the recovery plays will turn into growth stocks and be great investments but the cheap shares are not necessarily good value.

When the TMT (technology, media and telecoms) “bubble” burst in 2000, value stocks out-performed for five years. But those who bought into growth in the middle of this phase did extraordinarily well when growth returned. As it turned out, it had not been so much a “bubble” as a false start in the technology-driven bull market.

There is no sign that the transformation of the global economy behind this is anywhere near complete. There may be plenty of examples of excess and over-valuation in corners of the market but there always are - not least in the early 1980s when the bull market was still young.

Ignore the Jeremiahs and use current market uncertainty to buy into quality growth companies and funds trading at reassuringly expensive prices.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Max has an Economics degree from the University of Cambridge and is a chartered accountant. He worked at Investec Asset Management for 12 years, managing multi-asset funds investing in internally and externally managed funds, including investment trusts. This included a fund of investment trusts which grew to £120m+. Max has managed ten investment trusts (winning many awards) and sat on the boards of three trusts – two directorships are still active.

After 39 years in financial services, including 30 as a professional fund manager, Max took semi-retirement in 2017. Max has been a MoneyWeek columnist since 2016 writing about investment funds and more generally on markets online, plus occasional opinion pieces. He also writes for the Investment Trust Handbook each year and has contributed to The Daily Telegraph and other publications. See here for details of current investments held by Max.

-

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?

Student loans debate: should you fund your child through university?Graduates are complaining about their levels of student debt so should wealthy parents be helping them avoid student loans?

-

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic Flaine

Review: Pierre & Vacances – affordable luxury in iconic FlaineSnow-sure and steeped in rich architectural heritage, Flaine is a unique ski resort which offers something for all of the family.

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.