The world in 2040: lunar tourism, the end of cash, a basic income for all

To celebrate 20 years of MoneyWeek, we asked you for your views on what will happen over the next 20 years. John Stepek reports on the results and gives the MoneyWeek view.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Over the past month or so, we’ve been exhorting you in the magazine and on our various social media channels to answer the following five questions to give us some insight into what you think the world may look like by 2040. We had a fantastic response – thank you for your votes and your emails. Read on to find out the full results, alongside some of the best comments – and the MoneyWeek view.

Will gold have hit $10,000 an ounce?

Results: 56% yes, 44% no

We wouldn’t be MoneyWeek if we didn’t ask this question, and interestingly, it’s the one you demonstrated the least conviction on (alongside the lunar tourism question). As we regularly point out, gold is a useful way to protect your portfolio against financial disorder generally, and rising inflation specifically. But is $10,000 a realistic scenario?

Article continues belowTry 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Most of those voting “yes” argued that gold’s appreciation would be the result of inflationary public spending by governments (see page 4). As Steve Ramsdale put it, “very few governments around the world will be mean with funds, as we’ve learned in recent years”. Of course, the answer to the question also depends on prospects for the dollar over the next couple of decades. As Gareth Smitham put it, “gold could be $1m an ounce by 2040, but it will still take ten ounces to buy a decent car”.

On the “no” side of the voting, most of the doubters simply felt that interest rates would have to rise and monetary sanity return before gold can reach the $10,000 mark. As Chris Thompson put it: “All good things come to an end and what goes down must come back up, meaning interest rates rise this decade and likely stay higher than in the last 12 years.” Others thought that governments simply wouldn’t allow it – as David Miller put it, “gold is too obvious and easy an escape from their financial repression”. Some more imaginative readers argued that technology might vastly increase the supply of gold. Charlie Payne noted that more than 30 years ago, scientists turned bismuth into gold using a particle accelerator. “Granted the cost was astronomical… however if you believe in Moore’s Law and the huge looming advances in artificial intelligence, printing gold doesn’t seem so far-fetched by 2040. That won’t do the gold price any favours”.

MoneyWeek view: Yes

When MoneyWeek launched in November 2000, gold was trading at around $260 an ounce, not far off an all-time low. It’s now around $1,900 an ounce (near its all-time high), more than seven times higher. Repeating that over the next 20 years would easily see us hit the $10,000 mark. For a more scientific take, earlier this year, fund manager and MoneyWeek regular Charlie Morris put together a model for valuing gold which implied that the gold price could be above $7,000 an ounce in 2030 given certain conditions, including inflation exceeding just 4%. So it’s not at all outlandish to think that gold could hit $10,000 given the right circumstances. The way things are going, we feel it’s more likely than not.

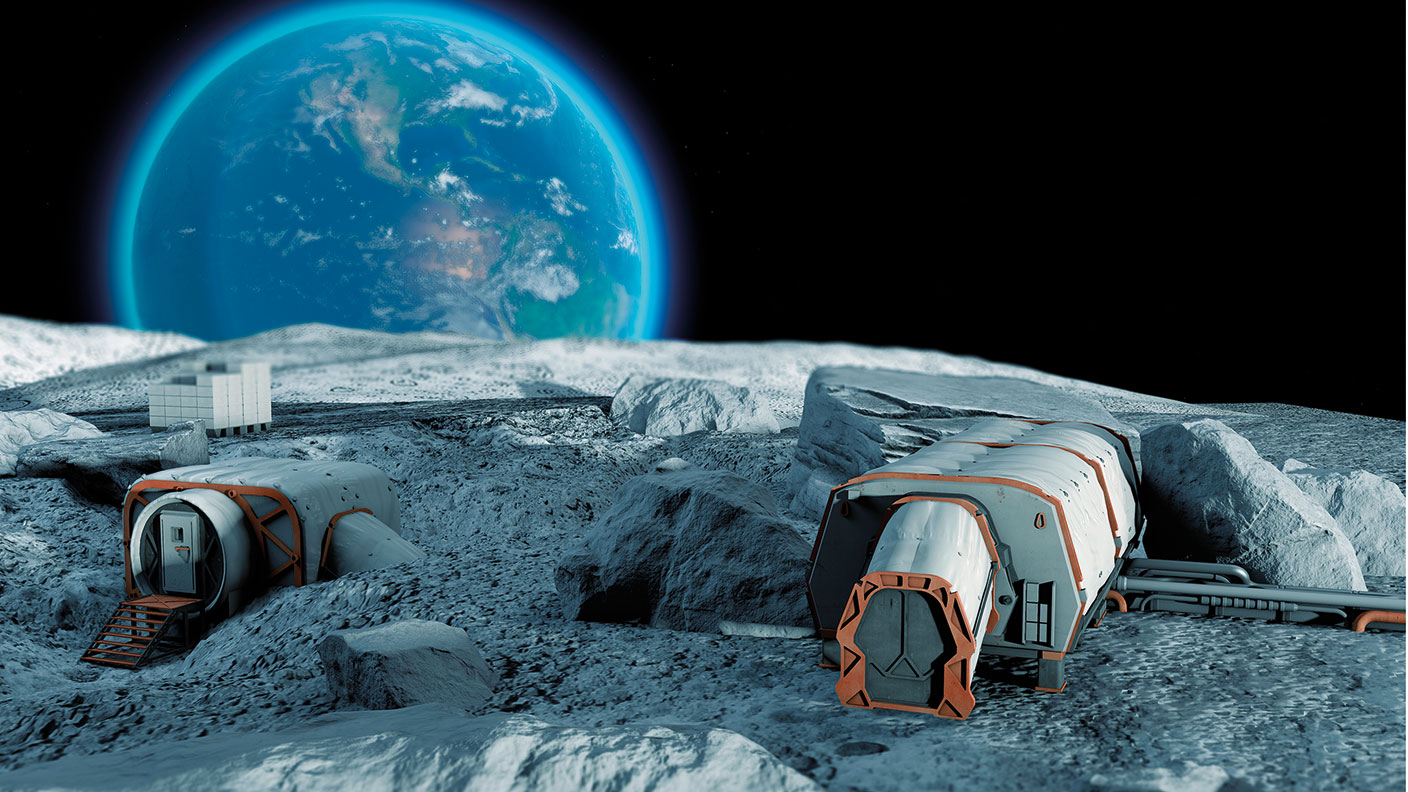

Will anyone have visited the Moon as a tourist?

Results: 56% yes, 44% no

The “no” voters on lunar tourism mostly couldn’t see the point. Chris Earnshaw took a more practical view, noting that while several people had already pre-booked tourist flights outside the Earth’s atmosphere, “the duration of a flight to the Moon is significantly longer than a flight round the Earth so will require a certain fitness level and an age probably of no more than 40 years old. No doubt someone will be able to afford it but the limitations lead me to say ‘no’.”

In the “yes” camp, Aidan Powlesland was more upbeat. “A tourist is already due to fly around the Moon in 2023, courtesy of SpaceX. With the US committed to a constantly occupied Moon base by 2028, it is hard to imagine the private sector sitting on its hands for the subsequent 12 years.” Meanwhile, Ian Lang had an interesting, if somewhat dystopian take: “The answer is ‘as good as’... By 2040, many of us will be spending most of our lives in haptic suits in virtual reality… holidays will be in virtual reality – skiing will continue even though the glaciers will have melted – and holidays on the Moon will be quite common.” Let’s hope it doesn’t come to that.

MoneyWeek view: Yes (sort of)

Clearly it’s technologically possible to put people on the Moon. And non-astronauts have already paid to go to the International Space Station (ISS). So the demand – however narrow or expensive – is there. So our view would be a qualified “yes” – by 2040, we will likely have seen a tourist on the Moon in the same way as we’ve already seen a handful of highly-trained wealthy “tourists” on the ISS. But we suspect it’ll be a lot longer before there are regular lunar shuttles.

Will any country have banned physical cash?

Results: 75% yes, 25% no

As far as most of you are concerned, if there’s one sure thing to bet on by 2040, it’s that cash’s days are numbered. The “yes” votes split into two camps. Some thought that cash will simply become obsolete. As Gareth Smitham put it, “there was no need to ban cheques – they just became redundant”. Others felt it was likely in smaller, more tech-savvy nations. “I hope that in the UK we’ll stick with a ‘cash-light’ system rather than moving to cashless,” wrote Catriona James. But “somewhere small and under fairly tight central control”, with a youthful population, such as Singapore or South Korea, might go the whole way.

The “no” voters either saw it as a step too far, even for authoritarian governments, while others saw pure practicality as a major hurdle. As Sheila Steele notes: “What happens if we have a nationwide power cut?”

MoneyWeek view: Yes

Given the number of countries looking into the idea and the tempting level of social control on offer, we’d be surprised if someone doesn’t at least try – probably in the wake of one of the periodic financial crises that no doubt await us over the next two decades. The odds increase greatly if any country introduces a central bank digital currency.

Will Amazon still be one of the ten most valuable companies in the world?

Results: 61% yes, 39% no

Given what it says about economic dynamism and competition, a worrying number of you are convinced that Amazon will still be one of the world’s most valuable companies in 20 years. As Brian McCluggage put it, Amazon “has a huge competitive moat that no other company will be able to overcome. Its biggest threat? Government, not competition.”

That reasoning lay behind many of the “no” votes, with many arguing that while Amazon itself will no longer be in the top ten, that’s only because it will either have been broken up or will have spun off parts of itself. As Bert Molsom put it, “I do not believe the present Amazon will be one of the ten most valuable companies, but I would suggest that parts of the present Amazon could potentially be three to five of the ten most valuable… Amazon Cloud, Amazon Logistics, Amazon Retail”. Yet as Ted Wainman argues, a lot can happen in 20 years: “80% of the jobs in 2040 do not exist right now, just as ‘head of social media’ or ‘influencer’ did not exist 20 years ago. The ten most valuable companies in the world have not yet been founded. They are the companies that will successfully exploit the opportunities of 5G, the ‘internet of things’, blockchain – or another technology that we don’t know about yet.”

MoneyWeek view: No

The “winner-takes-all” nature of the tech revolution has often been remarked upon, but here at MoneyWeek we still have a lot of faith in the power of competition. While Amazon may well still be a force to be reckoned with in 2040, its position in the eco-system will have changed (in much the same way as Microsoft remains powerful, but nowhere near as dominant as it was 20 years ago).

Will any government have operated a universal basic income scheme for more than a year?

Results: 64% yes, 36% no

Universal basic income (UBI) – the idea of one government benefit that everybody gets, regardless of circumstances – has appeal on both left and right, and most of you think it will happen somewhere. As Colin Jones-Evans put it, “probably only in one or two northern European countries. But we could be surprised by a small state such as Brunei or Qatar, but likely limited to natural born citizens.” Martin White points out that the UK’s tax credits and benefits system is already not far off providing a UBI – over time, the cost of extending it to everyone could be offset by “significant savings in the administration of the benefits available today, most of which would be eliminated to some extent.”

Yet as Richard Harrison points out, that might well be the problem. UBI “is only practical and affordable if all other forms of welfare are suspended, and no government will be allowed by the people to do that”.

MoneyWeek view: Yes (sort of)

We suspect that the purest form of UBI – one accompanied by the scrapping of all existing benefits – probably will prove a step too far. But the appeal of the idea won’t go away, and if you accept (as we do) that politicians will embrace modern monetary theory (MMT) and the unlimited money printing it promises, then an attempt by at least one nation at some form of wholesale UBI seems inevitable. Whether it can survive for more than a year is another question.

Related content

The world in 2040: expect water shortages and a bellicose China

The world in 2040: five potential market movers

Five top investment trusts to buy and forget until 2040

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.