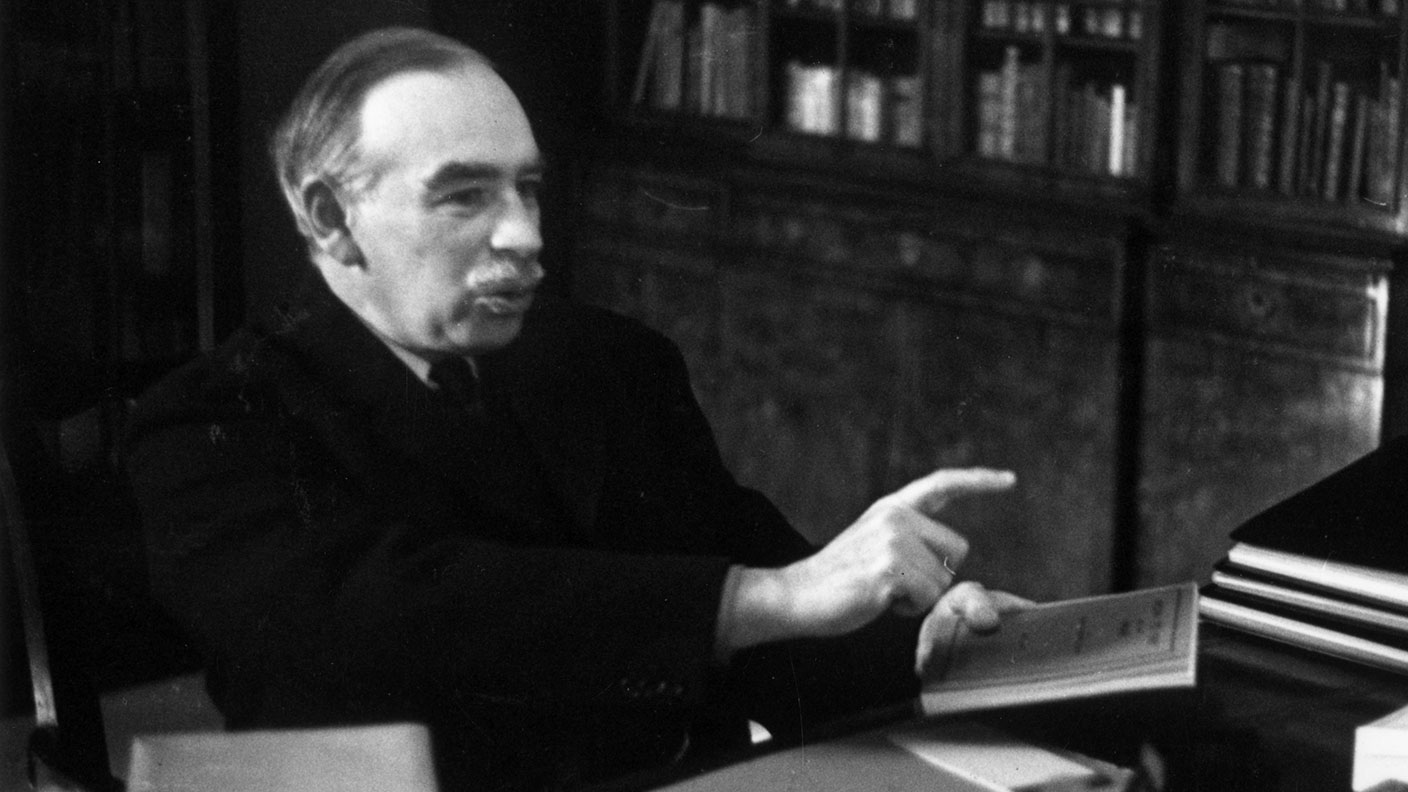

How John Maynard Keynes learned the folly of market timing

In an extract from his book The Sceptical Investor, John Stepek explains how the great economist John Maynard Keynes came a cropper when he first started investing – and how he turned his fortunes around.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

John’s out of the office today and tomorrow, so we’ve got a couple of extracts from his book on contrarian investing, The Sceptical Investor (published last year with Harriman House).

This morning’s piece is about how the great economist John Maynard Keynes came a cropper when he first started investing – and managed to turn his fortunes around by cultivating mental flexibility.

Keynes was smarter than most people – but not the market

John Maynard Keynes is of course, best known for being one of the most important thinkers in economics. But he was also a prolific, and eventually, very successful investor.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

When Keynes (allegedly – there is no primary source that I’m aware of for this quote) warned that “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”, he was speaking from experience.

Keynes was perhaps the last human being on earth that you would describe as possessing intellectual humility. Both his education and his temperament led him to feel that he was a man apart from the norm – a cut above, both intellectually and morally.

The son of a pair of upper-middle-class academics, he won a scholarship to Eton and excelled. As Robert L. Heilbroner observes in a review of Robert Skidelsky’s biography of Keynes in the New York Times, “Keynes won nearly every competition he ever entered, a performance not likely to encourage humility in a developing personality.”

He was also a deeply contrarian thinker. He had no respect for conventional sexual or social attitudes (notes Heilbroner: “The aristocracy he regarded as absurd ... the proletariat as ‘boorish’”), but nor was he a ‘conventional’ bohemian – he was regarded as something of an outsider and as too close to the establishment by fellow members of the artsy Bloomsbury group.

Also, like many of his peers, he was a keen eugenicist up until he died. You don’t get much more intellectually arrogant than believing that you have the right – the responsibility, even – to promote selective breeding among the lower orders.

In short, Keynes believed he was smarter than the crowd, and as such, he thought he could outsmart them. And in his early investment career, that’s what he aimed to do.

The dangers of market timing

In A Treatise on Money (1930), Keynes noted that (my emphasis added) “it may often profit the wisest to anticipate mob psychology rather than the real trend of events, and to ape unreason... so long as the crowd can be relied on to act in a certain way, even if it be misguided, it will be to the advantage of the better-informed professional to act in the same way – a short period ahead.”

So Keynes grasped that crowds were psychologically flawed (the idea of market efficiency was a while away into the future) and there was nothing wrong with that view.

The trouble was, he took the wrong lesson from it.

Keynes was arrogant enough to believe that he could not only anticipate the errors of the crowd, but that he could also copy those errors before the crowd had even made them, thus profiting from their predictable mistakes.

In short, he decided the path to profits was to second-guess the market, and he believed that it would be a simple enough task to remain one step ahead of the fools he was competing with.

For a while, he did fine with this approach. He had the insouciant approach to money that only those who’ve never lacked or lost it can enjoy. In 1920, he wrote to his mother: “Money is a funny thing ... [with] a little extra knowledge and experience of a special kind, it simply keeps rolling in.”

In another letter to his father, he wrote: “Win or lose, this high stakes gambling amuses me.” It’s the sort of casual-yet-secretly-thrilled boast that you hear from anyone who happens to get lucky when they start out trading or investing. It’s also usually a sure sign that they’re going to come a cropper further down the line.

And that’s what happened. In 1928, Keynes was wiped out in a commodities crash, which forced him to sell the majority of his share portfolio.

The remnants of said portfolio were then almost entirely lost in the crash of 1929. As Justyn Walsh notes in his book, Keynes and the Market, Keynes’ net worth fell by more than 80% to less than £8,000.

So how did he turn it around?

How Keynes discovered the joys of value investing

At the time he lost his own money in the stockmarket crash of 1929, Keynes was already involved in helping with the investments of various institutions, including King’s College, Cambridge, his alma mater. Fortunately for them, while he used the same sort of investing style as for his own portfolio, he didn’t bet as aggressively.

As a result, Keynes was lucky enough to have the resources to draw upon to start again. But he was also flexible enough to shift strategy, rather than trying to pursue the same doomed system.

He noted that his market-timing system (which he’d given the somewhat grandiose name of “credit cycling”) required “abnormal foresight” and “phenomenal skill”.

He would later go on to explain, in a memo to King’s College estates committee, that attempting to time the market “is for various reasons impracticable and indeed undesirable. Many of those who attempt it sell too late and buy too late, and do both too often, incurring heavy expenses and developing too unsettled and speculative a state of mind”.

He realised that, for him at least, investment success hinged not on second-guessing the crowd, but on spotting inexpensive yet promising companies that had been neglected by the market, investing in them, and being patient (value investing, in other words).

In the same memo to King’s, he outlined his new approach. He now preferred to hold “a careful selection of a few investments ... having regard to their cheapness in relation to their probably actual and potential intrinsic value over a period of years ahead and in relation to alternative investments at the time.”

And in 1944, he emphasised the need to avoid what was popular, in a letter to Sir Jasper Ridley (at Eton). “The central principle of investment is to go contrary to the general opinion, on the grounds that if everyone agreed about its merit, the investment is inevitably too dear and therefore unattractive.”

In other words, he found situations where it was clear to him that the crowd was wrong, and then he settled back to wait until the crowd woke up to its error. Within six years, he had recovered spectacularly from his earlier losses, notes Walsh, “parlaying net assets of just under £8,000 at the end of 1929 to more than £500,000 only six years later.”

Overall, according to performance data compiled by Cambridge Judge Business School’s David Chambers and Elroy Dimson, Keynes managed annualised returns of around 5.7% between 1924 and 1932. But after changing his style, from 1933 until his death in 1946, he made closer to 13% a year.

That’s an impressive return, made all the more impressive by the fact that it was achieved during a time period that included World War II, and also that it was achieved without dividend reinvestment – the dividends were used to provide an income for the college.

When he took over as bursar of King’s College, Cambridge in 1924, the college had £285,000 in funds. By the time he died in 1946, the pot had grown to £1.2m.

If you enjoyed this extract, you can pick up a copy of The Sceptical Investor here.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Financial education: how to teach children about money

Financial education: how to teach children about moneyFinancial education was added to the national curriculum more than a decade ago, but it doesn’t seem to have done much good. It’s time to take back control

-

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon Valley

Investing in Taiwan: profit from the rise of Asia’s Silicon ValleyTaiwan has become a technology manufacturing powerhouse. Smart investors should buy in now, says Matthew Partridge

-

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive month

Halifax: House price slump continues as prices slide for the sixth consecutive monthUK house prices fell again in September as buyers returned, but the slowdown was not as fast as anticipated, latest Halifax data shows. Where are house prices falling the most?

-

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?

Rents hit a record high - but is the opportunity for buy-to-let investors still strong?UK rent prices have hit a record high with the average hitting over £1,200 a month says Rightmove. Are there still opportunities in buy-to-let?

-

Pension savers turn to gold investments

Pension savers turn to gold investmentsInvestors are racing to buy gold to protect their pensions from a stock market correction and high inflation, experts say

-

Where to find the best returns from student accommodation

Where to find the best returns from student accommodationStudent accommodation can be a lucrative investment if you know where to look.

-

The world’s best bargain stocks

The world’s best bargain stocksSearching for bargain stocks with Alec Cutler of the Orbis Global Balanced Fund, who tells Andrew Van Sickle which sectors are being overlooked.

-

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in Britain

Revealed: the cheapest cities to own a home in BritainNew research reveals the cheapest cities to own a home, taking account of mortgage payments, utility bills and council tax

-

UK recession: How to protect your portfolio

UK recession: How to protect your portfolioAs the UK recession is confirmed, we look at ways to protect your wealth.

-

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage rates

Buy-to-let returns fall 59% amid higher mortgage ratesBuy-to-let returns are slumping as the cost of borrowing spirals.