The year trust became the currency in the art market

Collectors looking for accountability are turning to smaller dealers, says Sarah Ryan of New Blood Art

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

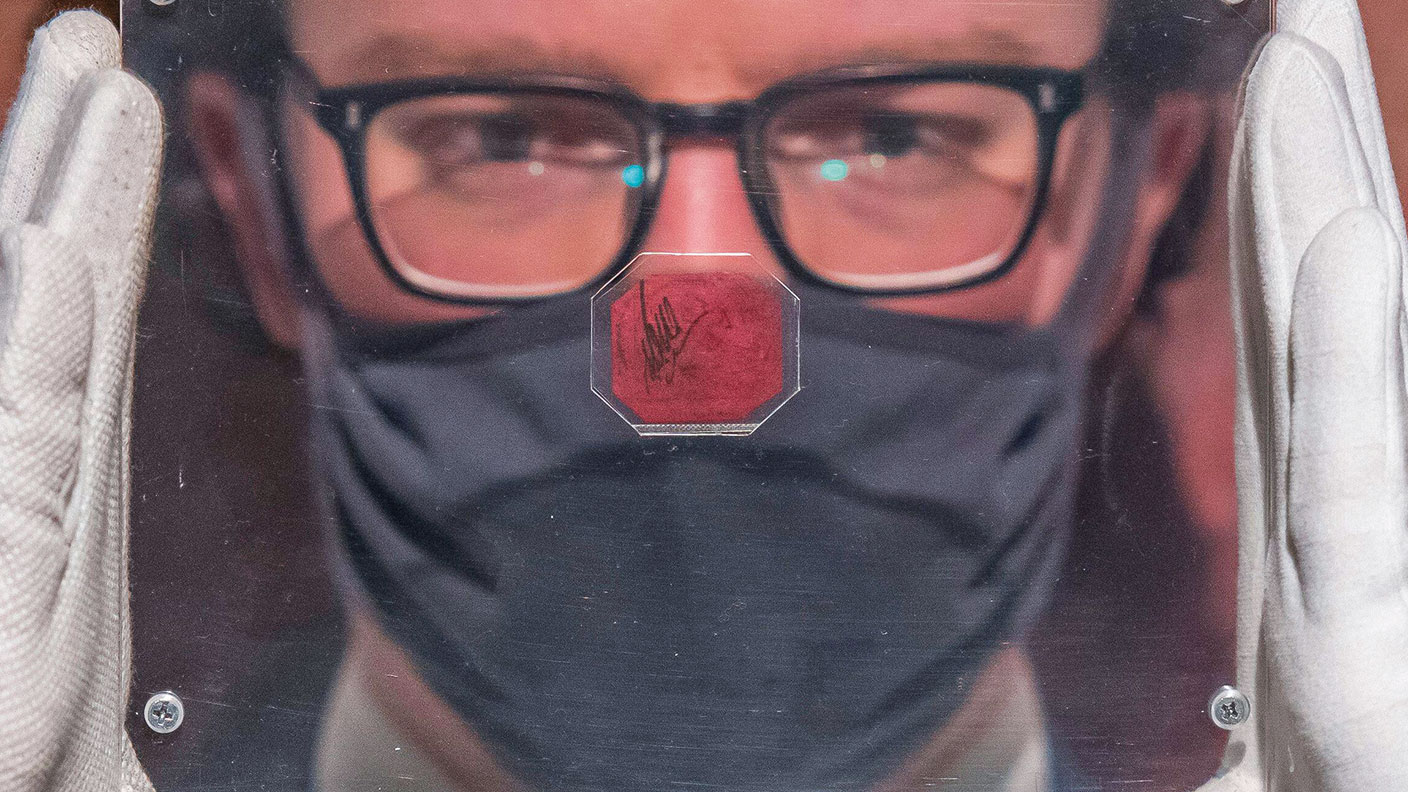

In 2024, nearly $7.7 billion less was spent on art than the year before, that’s a 12% drop in global sales, according to the latest Art Basel and UBS Art Market Report. Despite this, the overall number of transactions increased by 3%.

So activity and appetite haven’t fallen, but increased. Spending is down, yes, but participation is up.

The market isn’t shrinking, it’s shifting. Buyers are buying differently. The market is actually moving fast. Not collapsing. Reconfiguring.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The 12% global decline is largely driven by China’s 31% drop. A $3.77 billion contraction in one region accounts for nearly half the total global fall.

The global 12% decline isn’t evenly distributed, it’s front-loaded. If we were to strip that single figure out, what remains is perhaps a quiet reconfiguration: energy redistributed into smaller segments, younger buyers, and more intimate transactions.

So we don’t know how much of what we’re seeing is real, and how much has been distorted by that c. $4 billion rupture in China. The rupture itself was driven by a spike in non-payment – up 41% in China in 2024 – leaving billions in agreed sales unpaid.

Was the China drop so severe that it threw off the initial dataset? And did UBS fully account for that before drawing conclusions about things like buyer age, artist profile, price brackets? I haven’t yet had a chance to check this with UBS, and there’s certainly no accusation, but I think the question is worth asking.

Excuse me if I’m misunderstanding how these reports are consolidated, I’m not an analyst, but when non-payment is this widespread, it starts to raise structural questions. If a sale was originally recorded at auction, but the payment never arrived, was that sale removed everywhere it appeared? Can we still trust the reported increase in younger buyers, or were those figures partly driven by sales that later defaulted? Can we still rely on the price bracket analysis, or were those numbers also shaped by transactions that never completed?

All this underscores the risks represented by the art market’s lack of regulation. Money, value, and intent can move through it without friction, oversight, or traceability, leaving the market open to both exploitation and corruption (through laundering). This is why art companies sometimes draw sudden institutional scrutiny, with banks freezing accounts or HMRC launching reviews. But this same lack of regulation is also what makes the system vulnerable to something else now playing out in real time: people agreeing to buy artworks, then not paying.

Trust is the basis of all relationships, not just in the art world. The global art market fundamentally relies on trust because it’s unregulated. In most regions, that trust still holds. But in China, it’s broken down. And when trust collapses in an unregulated system, the surrounding structures – legal, financial, cultural – can’t intervene. They’re not designed to. There’s no enforcement mechanism. No fallback. Just collapse. The financial rupture is a symptom of something deeper: a collapse in trust that threatens the stability of the unregulated nature of the market.

Perhaps this is an indictment on the zeitgeist more generally – culturally, we’re less accountable. There’s more anonymity, less traceability. People can write a terrible comment online and then disappear. The shift is psychological, relational. It’s not just the market, it’s the culture.

In the West, defaults are rare and taken seriously. In China, their rise signals something more serious: a market teetering on the edge of credibility.

Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips have already been scaling back. Christie’s cancelled its spring Hong Kong auction in 2024. Sotheby’s and Phillips have reduced the size and ambition of their China-based sales. Several Western auction houses are shifting their focus back to New York, London, and Paris, where enforcement is clearer and buyer confidence is stronger.

The rationale for further retreat is clear. A market where sales don’t convert to payment isn’t just unprofitable, it’s reputationally dangerous. You can’t afford defaults on top lots. You can’t build long-term confidence in a system that doesn’t honour its own transactions.

At this scale, non-payment destabilises everything: consignors lose faith, buyers hesitate, brands erode. And without regulation, when someone defaults, no authority steps in.

Unless something changes structurally in China, it’s likely that major Western houses will keep retreating from the market.

The art market thrives on discretion – prices, buyers, terms – much of it stays hidden. That makes it easier for buyers to overcommit, delay payment, disappear, or even use non-payment as a post-sale tactic.

Enforcement is left to individual institutions. Each auction house or gallery is responsible for chasing its own defaults. There’s no collective mechanism. No shared blacklist. A buyer can default in one place and keep bidding elsewhere.

Buyers’ behaviour is changing

Happily, and it strikes me this is no coincidence, there’s a recalibration happening lower down the market, where relationship remains at the centre: more sales at lower price points, more activity in quieter corners.

Sales of work under £5,000 are up 13%. Smaller dealers – those with annual turnover under $250,000 – saw a 17% rise. And that figure matters, because it’s structurally trustworthy. These are relationship-led transactions: the kind where you agree to the deal, transfer the money, and the work changes hands. There’s little scope for non-payment. The relationship itself holds the exchange.

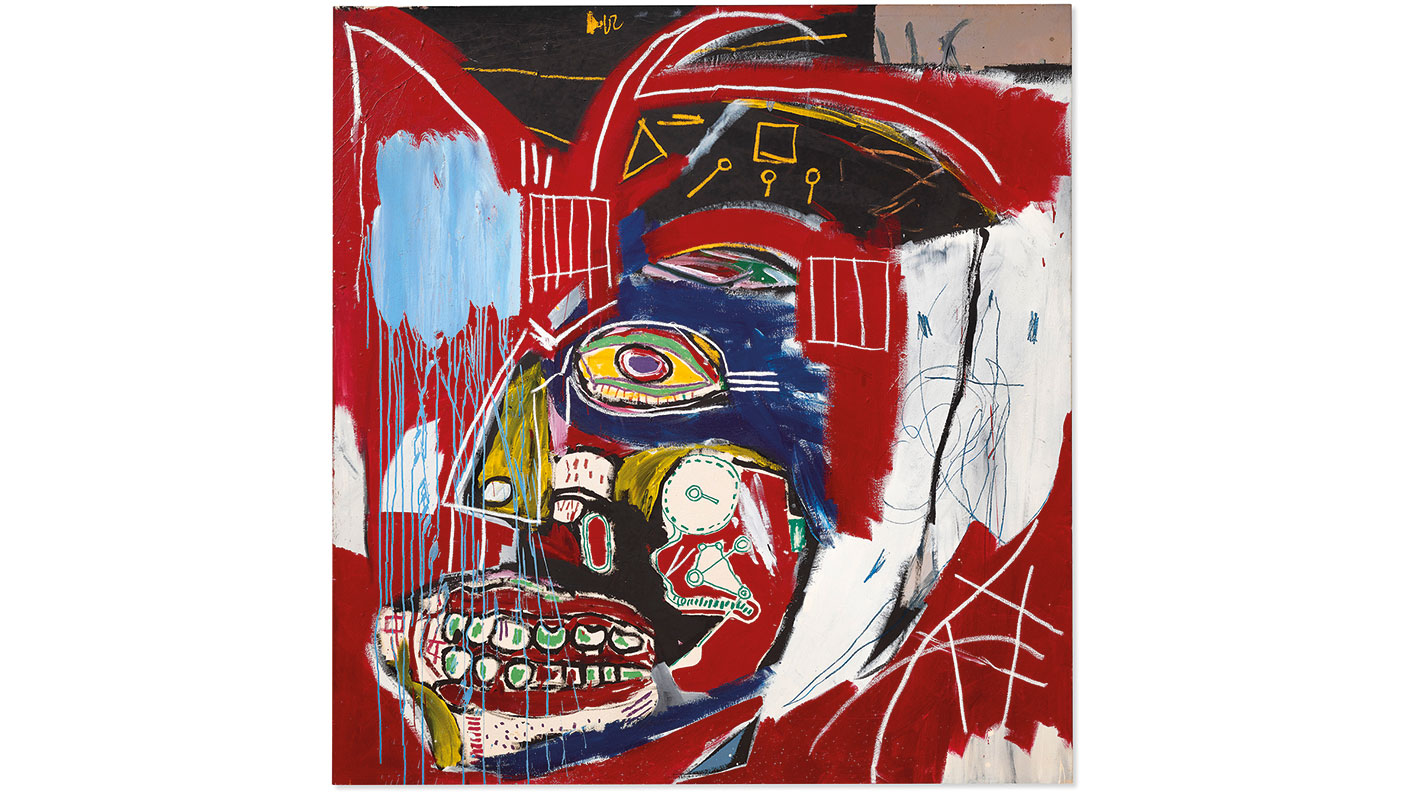

If the numbers can be trusted, there’s a shift happening – more young and new buyers are entering the market, and they’re not chasing big names or big prices. They’re finding work in smaller spaces, with emerging artists, through personal relationships and quieter transactions. The energy is moving away from spectacle and towards substance.

At the top end, the landscape is radically shifting. Take Marlborough Gallery, who closed in 2024 after nearly 80 years – not just a big gallery, but one known for exactly what the market claims to value now: long-term relationships, depth, trust, intimacy. And still, it didn’t survive.

Founded in 1946, Marlborough helped shape post-war British art. It represented Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Henry Moore, Frank Auerbach. Its legacy is inseparable from the evolution of modern British painting.

What distinguished Marlborough was its commitment to personal relationships with artists. This wasn’t a depersonalised gallery chain, it was a gallery built on trust and continuity. That it couldn’t sustain itself in today’s market points to something deeper: a structural shift in how art is sold, and what is seen as viable.

Marlborough’s roster included not only the giants, but also contemporary artists like Maggi Hambling and Catherine Goodman. Just months before closing, they signed Lorena Levi – an emerging artist we introduced to the market. They weren’t winding down. They were reaching forward.

Marlborough’s closure isn’t just one gallery shutting its doors. It marks a broader transformation. The market is shifting toward more intimate, relationship-based transactions – often at lower price points and outside traditional gallery systems. That decentralisation challenges legacy structures and forces a reassessment of how art is bought, sold, and valued.

In this context, Marlborough’s end becomes a marker of change. Even the most established institutions must adapt, or risk being left behind. Maybe some got too big. Maybe they lost the human thread.

What’s clear, whatever the reason, is that the momentum is now elsewhere. With smaller dealers. Younger artists. Quieter transactions. People want something human. And maybe it’s no surprise that people are turning to smaller dealers, quieter purchases, places where they can shake someone’s hand. Because when the relationship disappears, anonymity creates space for people to act without accountability. And as we move headlong into an AI-shaped world, that desire may only grow.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Sarah Ryan writes about alternative investments for MoneyWeek. She is the founder and director of New Blood Art, an innovative online gallery for exceptional early-career artists, which helps to make collecting original fine art accessible to more people.

Many of the artists Sarah has featured have gone on to perform exceptionally well commercially, earning her a reputation among fans of alternative investments.

Sarah has a degree in fine art from London Metropolitan University and a PGCE in art education from Cambridge University and previously worked as a teacher.

Sarah also holds a diploma in integrative counselling & psychotherapy from the University of Roehampton, and is a practising psychotherapist.

-

Should you buy an active ETF?

Should you buy an active ETF?ETFs are often mischaracterised as passive products, but they can be a convenient way to add active management to your portfolio

-

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year end

Power up your pension before 5 April – easy ways to save before the tax year endWith the end of the tax year looming, pension savers currently have a window to review and maximise what’s going into their retirement funds – we look at how

-

Affordable Art Fair: The art fair for beginners

Affordable Art Fair: The art fair for beginnersChris Carter talks to the Affordable Art Fair’s Hugo Barclay about how to start collecting art, the dos and don’ts, and more

-

Fine-art market sees buyers return

Fine-art market sees buyers returnWealthy bidders returned to the fine-art market last summer, amid rising demand from younger buyers. What does this mean for 2026?

-

Reinventing the high street – how to invest in the retailers driving the change

Reinventing the high street – how to invest in the retailers driving the changeThe high street brands that can make shopping and leisure an enjoyable experience will thrive, says Maryam Cockar

-

Where to look for Christmas gifts for collectors

Where to look for Christmas gifts for collectors“Buy now” marketplaces are rich hunting grounds when it comes to buying Christmas gifts for collectors, says Chris Carter

-

Sotheby’s fishes for art collectors – will it succeed?

Sotheby’s fishes for art collectors – will it succeed?Sotheby’s is seeking to restore confidence in the market after landing Leonard Lauder's art collection, including Gustav Klimt's Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer

-

Napoleon’s bicorne headgear, the original MAGA hat, could fetch €800,000

Napoleon’s bicorne headgear, the original MAGA hat, could fetch €800,000Collectables Napoleon would not be out of place in Trump’s America, says Chris Carter

-

Grab a piece of art – or music – with fractional ownership

Grab a piece of art – or music – with fractional ownershipAdvice Fractional ownership allows you to buy shares in assets such as stamps, paintings and music royalties, says David Stevenson.

-

The high-end art market is still on fire

The high-end art market is still on fireReviews The art-market billionaires are coming out of lockdown. Chris Carter reports