What caused the Birmingham bin strike – and what does it mean for British businesses?

The Birmingham bin strike is the fallout from an equal-pay claim brought by female cleaners. That bodes ill for the rest of British business

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

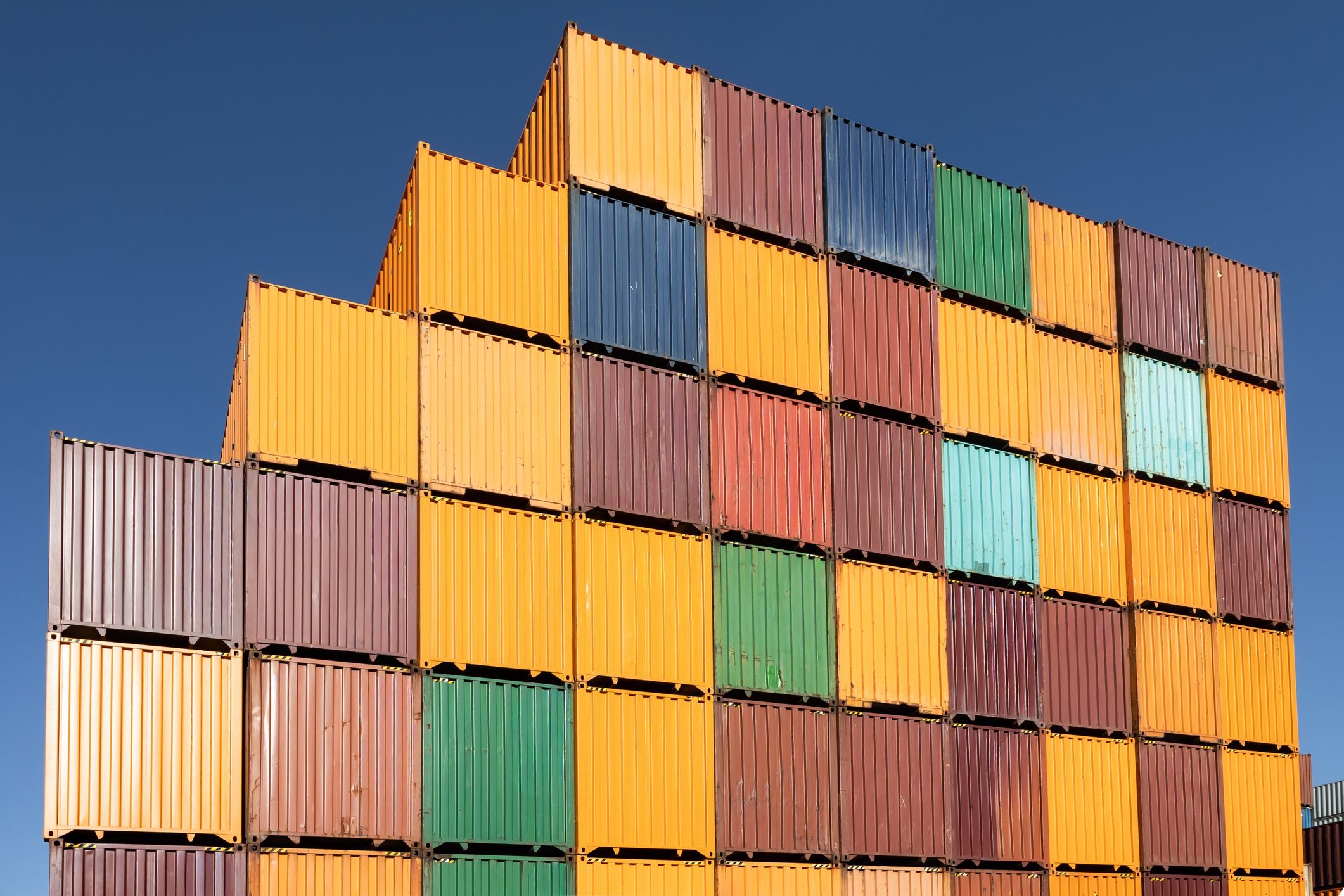

What’s going on in Birmingham?

The rubbish continues to pile up in the streets – to the disgust of residents and the delight of the local rat population – as the city’s binmen last week rejected the latest pay offer from the municipal authorities. It’s an intractable row, with no immediate resolution in sight. But what’s getting lost in all the media coverage, says Ross Clark in The Spectator, is a clear-eyed view of what caused the stand-off. The strike, which began on 11 March, is the “fallout of Birmingham City Council going bust as a result of an equal-pay claim brought by [female] cleaners who complained they were not paid as much as [male] binmen”. Their successful case was built on the allegation of sex discrimination, and based on the concept of “work of equal value”. That’s a worryingly nebulous concept, which has the potential to wreak much havoc on UK business, says Clark – and we can expect things to get worse once Labour’s new “Fair Work Agency” muddies things further.

How is “equal work” defined?

Employers have been required to offer men and women equal pay for equal work since the Equal Pay Act in 1970. The concept was widened under the Equality Act 2010, and today it applies to employees (including agency workers) no matter whether they are full-time, part-time, apprentices, or on temporary or freelance contracts.

When it comes to defining “equal work”, there are three kinds of equality recognised by the law. The first two are “like work” (work that involves similar tasks, knowledge and skills), and “work rated as equivalent” (under a job-evaluation scheme). The third type of equal work is the most controversial and hard to define; namely, the “work of equal value” at the centre of Birmingham’s woes. This refers to “equal” job roles that might not in fact be remotely similar, but are judged to be equivalent in terms of the effort and skill needed to carry them out, and the level of decision-making involved.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Sounds quite subjective?

Indeed – and it’s that that has proved a boon for (mostly) female workers and even more so for their lawyers. The concept of “equal pay for work of equal value” was enshrined in law in 1984; the Conservative government was obliged to legislate under European Community rules.

To make a claim, a worker needs to identify a “comparator” employee – someone of the opposite sex within their organisation, or an “associated” organisation – and show that their pay or conditions are worse. This is a difficult thing to do – and there were relatively few cases until 1999, when legal changes (a new Europe-wide right to claim six years’ extra back pay rather than just two; the relaxation of rules on “no-win no-fee” lawyers) improved things for plaintiffs.

Ever since, it has led to a multitude of legal cases – originally in the public sector and now increasingly in the private sector, too – in which (for example) female cleaners and carers have argued that their work was just as valuable as that of dustmen or caretakers. One of the most high-profile cases, involving Asda, finished (for now) its ten-year crawl through the courts in January.

What happened in the Asda case?

The judges decided in favour of tens of thousands of shop-floor workers (most of them female) who were suing Asda for being paid less than their colleagues (most of them male) in warehouses.

It’s the biggest private-sector case so far, involving at least 60,000 staff. The case work was certainly thorough, says The Economist: “Detailed job descriptions submitted for the judges’ consideration spanned over three times the length of the complete works of Shakespeare.”

Of the 14 store-based roles they analysed, they concluded that 12 were of equal value to the warehouse-based roles. Although the plaintiffs did not have to prove intentional sexism, Asda does now have to prove it had a good reason (a “material factor”) other than sex for the pay disparity. That could take another two years.

What if it can’t?

If the supermarket can’t justify the pay disparity, it will be on the hook for compensation of about £1.2 billion – plus higher ongoing wage costs of about £400 million (15%) a year.

Leigh Day, the law firm representing Asda’s staff, is also representing shop workers bringing claims against Tesco, the Co-op, Morrisons and Sainsbury’s; clothes-chain Next is already on the hook to pay compensation, possibly more than £30 million.

For free-market liberals, says Tim Worstall of the Adam Smith Institute, to argue about the equal value of work is “to commit a category error” akin to the one Marx made with his labour theory of value.

In reality, the “value” of work – the wages paid for it – is determined by the supply of workers able to do the job and the demand for them to do so. Thus, two different jobs can never be said to be of “equal value”, since the only useful measure we have of what a job’s worth is “what someone is willing to pay to get it done. How can it be otherwise in a market economy?”

How can it?

When policymakers decide that it can, and pass laws to make it so. But organisations can protect themselves in a number of ways against unequal-pay claims and ensure they are acting fairly, says Charles Cotton of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

Transparency: “Being transparent about pay and grading systems should avoid discrepancies that trigger equal-pay claims.”

Audits: conduct regular equal-pay audits to identify potential issues.

Action plan: identify risks around pay disparities and make a plan to resolve them.

Job evaluation: put a formal scheme in place that rates the value of each job to the organisation.

Salaries: do line managers tend to offer higher salaries to male new joiners?

High levels of managerial discretion can increase the risk of unequal pay. “The gavel-wielding hand is on the move at the (considerable) expense of the invisible hand,” says The Economist. It’s an ominous development: forewarned is forearmed.

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era

ISA reforms will destroy the last relic of the Thatcher eraOpinion With the ISA under attack, the Labour government has now started to destroy the last relic of the Thatcher era, returning the economy to the dysfunctional 1970s

-

'Expect more policy U-turns from Keir Starmer'

'Expect more policy U-turns from Keir Starmer'Opinion Keir Starmer’s government quickly changes its mind as soon as it runs into any opposition. It isn't hard to work out where the next U-turns will come from

-

Britain heads for disaster – what can be done to fix our economy?

Britain heads for disaster – what can be done to fix our economy?Opinion The answers to Britain's woes are simple, but no one’s listening, says Max King

-

Goodwin: A superlative British manufacturer to buy now

Goodwin: A superlative British manufacturer to buy nowVeteran engineering group Goodwin has created a new profit engine. But following its tremendous run, can investors still afford the shares?