Why we need to get a grip on our government

Our government is trying to do too much, enacting policies that are destructive to the private sector. It needs to drop the the feel-good nonsense and create policies that lead to long-term wealth, says Merryn Somerset Webb.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Is there a glut of oil on the way? It doesn’t feel like it at the moment. Years of well meaning lack of investment into fossil fuels have tightened the market (the effect being similar to that of the Opec crisis in the early 1970s) and most analysts are now assuming the supply and demand mismatch will last for some years to come. But is this just to make yet another extrapolation mistake?

In most commodity markets, the cure for high prices is high prices – and there is no reason to think this will be any different, says Max King in this week's magazine. Already, governments and investors are busily backtracking on their opposition to fossil-fuel investment and there is likely be a “significant supply response” from Opec, the US (shale) and Venezuela. This time next year and it may be that the £100 tank of petrol is nothing but a distant nightmare, something that could solve a lot of our problems.

The real causes of inflation

Not everyone is convinced by this. Barry Norris points out that investment in the search for new oil and gas reserves is down 66% on a decade ago, and in this week’s podcast Charles Schwab’s Liz Ann Sonders notes that the environmental, social and governance (ESG) agenda is very much at odds with support for fossil-fuel exploration.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

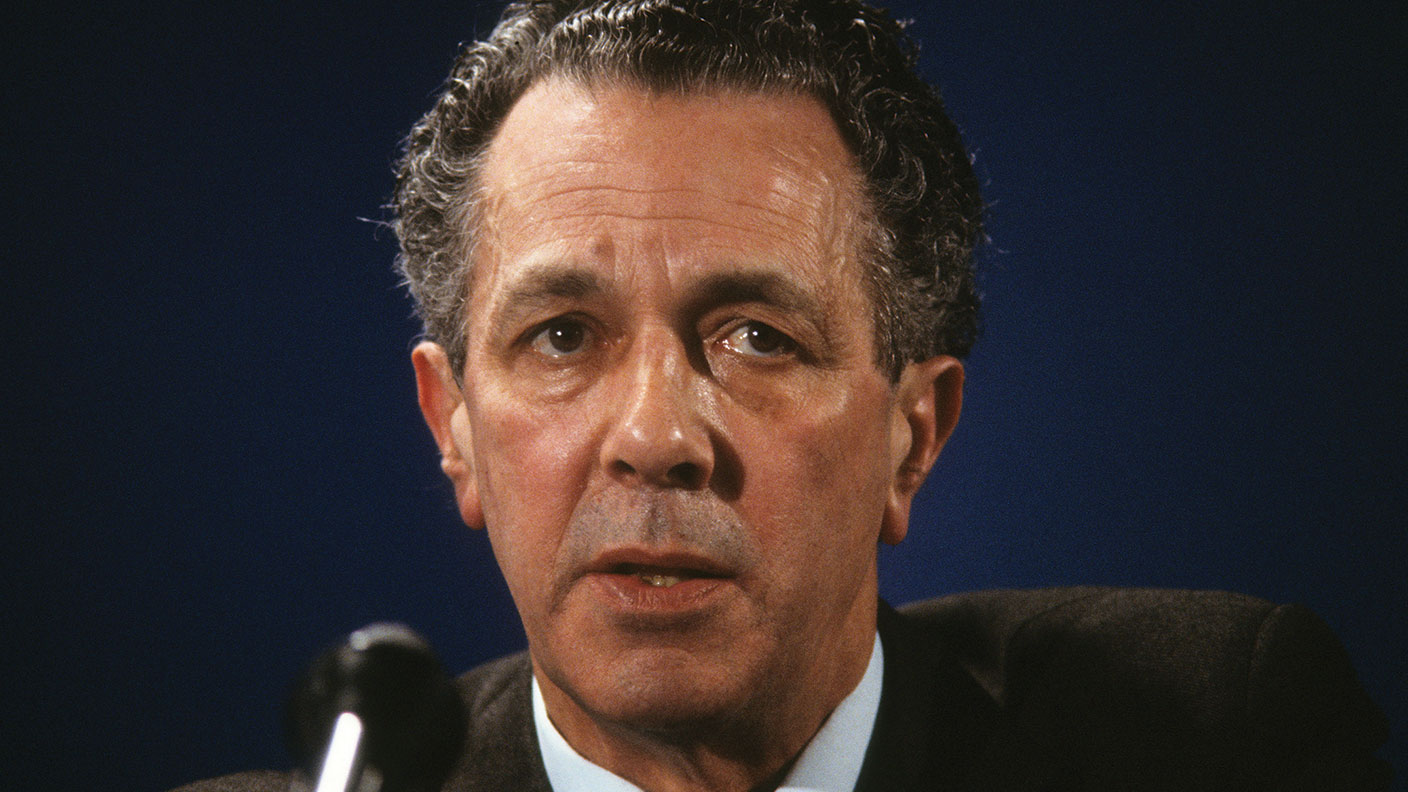

It also may not make the definitive difference the optimists think. The truth is that much as it suits politicians and central bankers to blame inflation on oil prices – and to claim oil prices are only up as a result of war in Ukraine – inflation is caused by governments. But inflation is really the result of politicians “trying to do too much too quickly”, says Andrew McNally of Equitile investments (quoting a 1974 speech from Keith Joseph, later Margaret Thatcher’s head of policy), creating and spending far too much money in the process.

This happened in the run up to 1974 when governments (terrified that they may again see the mass unemployment of the 1930s) tried to spend their way out of their problems. Government spending relative to GDP is at a historic high in the UK (albeit not quite as high as it is in many of our EU neighbours) and “higher inflation always follows higher spending”.

Our government is once again trying to do too much (see Matthew Lynn's column this week on why borrowing your way out of a crisis rarely works) and doing so while also enacting policies that are hugely destructive to the private sector – think lockdowns, the green agenda and the relentless rise of regulation.

Getting a grip on government

Note that the number of people working in the civil service is up 24% since 2016. The state is too big; it costs too much – and at some point it will be clear that it is crowding out the private sector. Not much long-term good can come of this. Oil prices may or may not self-correct, but unless governments get a grip, stagflation – and its nasty effects on our wealth and our living standards – will not.

MoneyWeek is in (fairly) rare agreement with The Economist on this matter: it is time for the UK to start making a few more of the hard choices that lead to long-term wealth and fewer of the feel-good ones that have got us where we are today. Markets like this kind of thing: by the end of the 1970s £100 invested at the top of the market was worth only £61 in real terms. By the end of the 1980s (after some work from Thatcher and Joseph) it was worth £261.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek Talks

Are money problems driving the mental health crisis? MoneyWeek TalksPodcast Clare Francis, savings and investments director at Barclays, speaks about money and mental health, why you should start investing, and how to build long-term financial resilience.

-

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change looms

Pensioners ‘running down larger pots’ to avoid inheritance tax as rule change loomsChanges to inheritance tax (IHT) rules for unused pension pots from April 2027 could trigger an ‘exodus of large defined contribution pension pots’, as retirees spend their savings rather than leave their loved ones with an IHT bill.

-

UK wages grow at a record pace

UK wages grow at a record paceThe latest UK wages data will add pressure on the BoE to push interest rates even higher.

-

Trapped in a time of zombie government

Trapped in a time of zombie governmentIt’s not just companies that are eking out an existence, says Max King. The state is in the twilight zone too.

-

America is in deep denial over debt

America is in deep denial over debtThe downgrade in America’s credit rating was much criticised by the US government, says Alex Rankine. But was it a long time coming?

-

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growth

UK economy avoids stagnation with surprise growthGross domestic product increased by 0.2% in the second quarter and by 0.5% in June

-

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%

Bank of England raises interest rates to 5.25%The Bank has hiked rates from 5% to 5.25%, marking the 14th increase in a row. We explain what it means for savers and homeowners - and whether more rate rises are on the horizon

-

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your money

UK inflation remains at 8.7% ‒ what it means for your moneyInflation was unmoved at 8.7% in the 12 months to May. What does this ‘sticky’ rate of inflation mean for your money?

-

Would a food price cap actually work?

Would a food price cap actually work?Analysis The government is discussing plans to cap the prices of essentials. But could this intervention do more harm than good?

-

The cost of petrol in the UK compared with the rest of the world

The cost of petrol in the UK compared with the rest of the worldNews The price of petrol in the UK went through the roof last year, but has since settled. We look at how UK petrol price compares with the rest of the world.