Why we need to chop off the “dead hand” of the Treasury

HM Treasury, the department in charge of long-term growth, fiscal policy, and departmental budgets, is a single bloated behemoth. It would be better to split the roles.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Recent weeks have seen yet another supposedly ambitious announcement from the government – in this case on the UK’s future energy security – first delayed and then radically scaled back in the face of objections from the Treasury.

Boris Johnson came to power promising to solve the social care crisis, make the UK a “science superpower”, “level up” the country and speed up progress to net zero carbon. All are noble ambitions, but all require massive long-term investment of a kind the Treasury appears determined to avoid, just as it pulled the plug on delivering the whole of HS2.

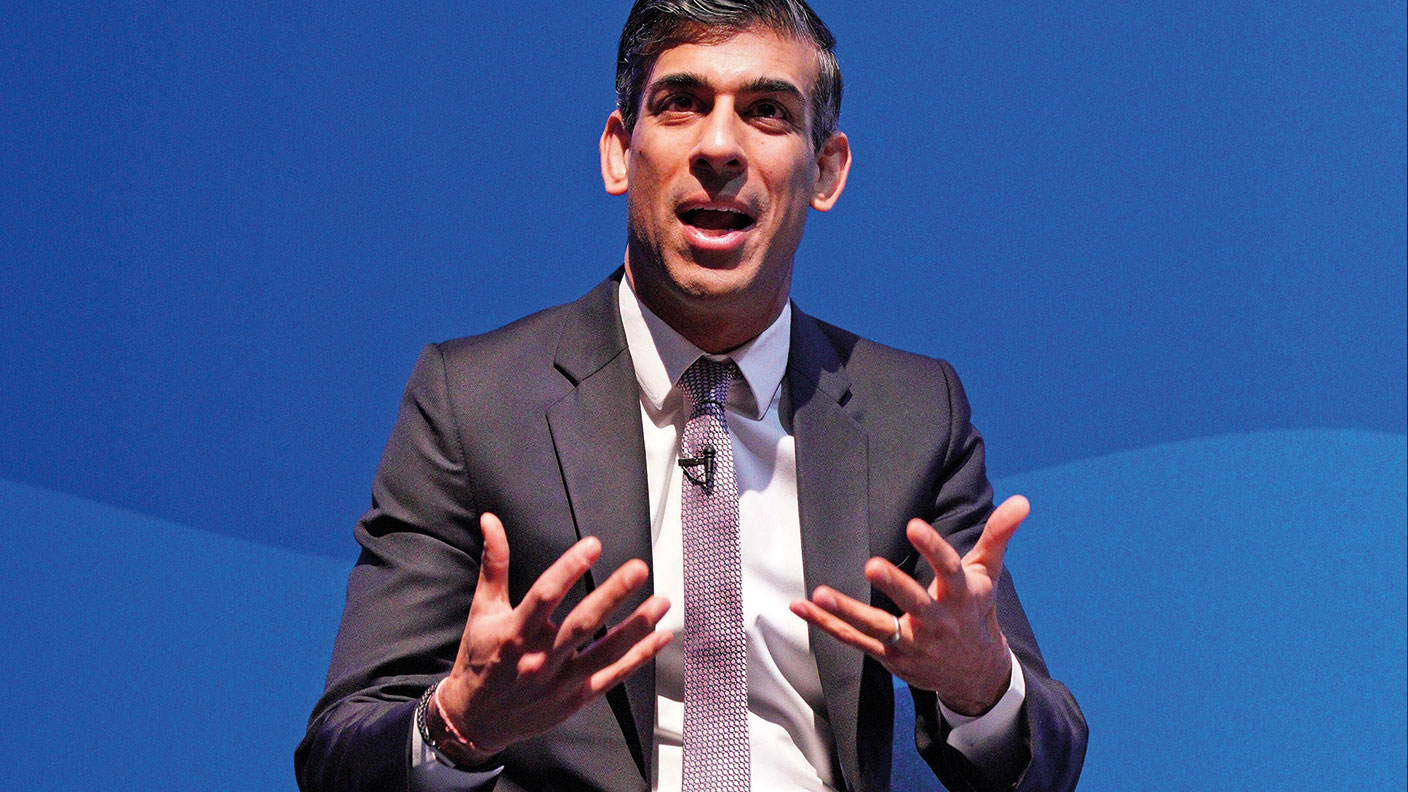

Most recently, Rishi Sunak’s lacklustre response to the current crisis over energy costs is proof that the chancellor has developed all the known symptoms of “Treasury brain”, says Eliot Wilson in CityAM. This unfortunate malady ends up affecting all chancellors and is “endemic” in the present Treasury – the symptoms being “instinctive parsimony, distrust of large-scale spending projects, a deeply possessive attitude towards taxpayers’ money and, most importantly in this case, appalling short-termism”.

Try 6 free issues of MoneyWeek today

Get unparalleled financial insight, analysis and expert opinion you can profit from.

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Isn’t fiscal stability important?

Yes, but it’s a means to an end, not an end in itself – and the Treasury is prone to confusing the two, say critics. The Treasury is not just in charge of fiscal policy, it’s the UK’s economic ministry, charged with steering long-term growth and prosperity.

Part of the problem is that in most developed economies the Treasury’s functions are spread across different departments of state. Here, the Treasury is both the economics ministry responsible for fostering policies that encourage long-term growth and the finance ministry responsible for fiscal policy and public-sector debt. It is also, third, in effect a budgetary ministry responsible for managing departmental spending.

Why does that matter?

Because the mega-ministry is an overmighty behemoth, dominating the whole domestic policy agenda and yet tasked with potentially conflicting aims that lead it to prioritise cost-saving at the expense of long-term benefits. It unbalances Whitehall by sucking in many of the most talented civil servants. It’s also the only department to send two ministers to cabinet (or three if you count the Treasury’s “First Lord”, the PM). In short, it’s too powerful.

In the post-war decades, the Treasury was the hub for “Keynesian demand-management”, says The Economist – while under Margaret Thatcher it drove the monetarist revolution. Under New Labour, the Treasury commandeered social policy; under the coalition of 2010-2015 it oversaw austerity. Now its instinctive caution and lack of long-term vision is hindering the kind of action needed to address the UK’s structural problems and cost of living crisis, critics say.

Critics such as who?

Left-wing voices have been arguing for years that the Treasury is a fundamentally conservative institution whose fiscal caution is against the national interest. But these days it’s not just the usual suspects making that case. The core problem with the Treasury, according to the FT’s chief economics commentator Martin Wolf, is that it is “institutionally sceptical about anything that comes from spending departments and is particularly sceptical about schemes for economic improvement”.

The Treasury is competent, but also “defensive and defeatist” – and its excessive caution is almost certain to doom the “levelling up” agenda to failure. It’s a “dead hand” on policy-making that needs to be “lopped off”. Wolf’s FT colleague Robert Shrimsley castigates the Treasury as a “complacent toad” that squats over government instilling it with short-termism and lack of ambition. Its “groupthink, innate fiscal orthodoxy” and resistance to the devolution of powers to the regions have long made it a “block to progress”, says Shrimsley. And given the weakness of this prime minister, that’s not going to change.

So should the Treasury be broken up?

It has been tried before, in the 1960s, when the Labour prime minister Harold Wilson – determined to push through a levelling-up-style “National Plan” for growth and investment – decided that a finance ministry focused on spending restraint could not also be charged with setting long-term economic strategy. Wilson’s solution was to split up the Treasury, handing some of its responsibilities to a new Department of Economic Affairs.

The idea, says George Dibb in the New Statesman, was that a “creative tension” between the Treasury and its upstart sibling would benefit the government overall. Alas, the arrangement led merely to turf wars and discord, while a balance-of-payments crisis engulfed Wilson’s government.

So what to do?

Other governments have toyed with reform. Gordon Brown, pre-1997, considered a plan to slim down the Treasury, but dismissed it on the grounds of the DEA precedent leading to “turf wars”. Later, “Operation Teddy Bear”, a plan mooted in 2003 by Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson, was aimed at clipping Brown’s wings by making the Treasury into a much-reduced finance ministry overseeing macroeconomics, and splitting off oversight of departmental spending. Brown, by now a powerful chancellor, saw them off.

In 2016, Theresa May created an expanded business department (BEIS) that trod on the Treasury’s toes, and was scaled back again after May left office. Even today, says Dibb, there are “echoes of the DEA experiment” in the joint No. 10 and No. 11 policy team set up by Dominic Cummings.

What Johnson’s ousted chief adviser realised was that there’s not much point in joined-up policy-making if that merely means joining it up to the dead hand of the Treasury, says Dibb. How should the UK prepare to meet the economic and fiscal challenges of the 21st century? “The answer is simple: we need to break up the Treasury.”

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

-

What do rising oil prices mean for you?

What do rising oil prices mean for you?As conflict in the Middle East sparks an increase in the price of oil, will you see petrol and energy bills go up?

-

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentary

Rachel Reeves's Spring Statement – live analysis and commentaryChancellor Rachel Reeves will deliver her Spring Statement on 3 March. What can we expect in the speech?

-

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’

UK small-cap stocks ‘are ready to run’Opinion UK small-cap stocks could be set for a multi-year bull market, with recent strong performance outstripping the large-cap indices

-

The scourge of youth unemployment in Britain

The scourge of youth unemployment in BritainYouth unemployment in Britain is the worst it’s been for more than a decade. Something dramatic seems to have changed in the labour markets. What is it?

-

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growth

In defence of GDP, the much-maligned measure of growthGDP doesn’t measure what we should care about, say critics. Is that true?

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton