Earnings estimates are a rigged game – especially in the US

The number of US stocks beating earnings estimates tells us only that guidance has deliberately been set too low

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

Of all the things that Donald Trump could claim are “rigged” against him, the number of jobs being added in the US economy is one of the oddest. Yes, there are real problems with statistics in many countries, and the situation has got worse since the pandemic. Firing the head of the statistics agency, as Trump did last week, is unlikely to fix that, especially if the replacement is picked for loyalty to him. However, the 258,000 cut to the estimated jobs added in May and June is completely in line with what you’d expect once in a while.

Data like these are prone to big revisions, sometimes long after they are first reported. One difficulty in trying to spot turning points in the economy using trends from past data is that the revised numbers we have now can sometimes be quite different from those reported at the time. Much of the information that statistics agencies collect is important in trying to understand long-term trends. But they are not reliable real-time signals. Investors, like Trump, could afford to take each release a little less seriously.

Earnings estimates are transparently biased

In fact, the prize for the most manipulated statistic in markets surely goes not to a government department, but to the private sector. Earnings estimates – and the ability of companies to beat them – are transparently a rigged game, especially in the US. If analysts’ estimates were an unbiased forecast of earnings, you’d expect companies to beat them 50% of the time and miss 50% of them. This doesn’t happen – on average, companies beat estimates significantly more often.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

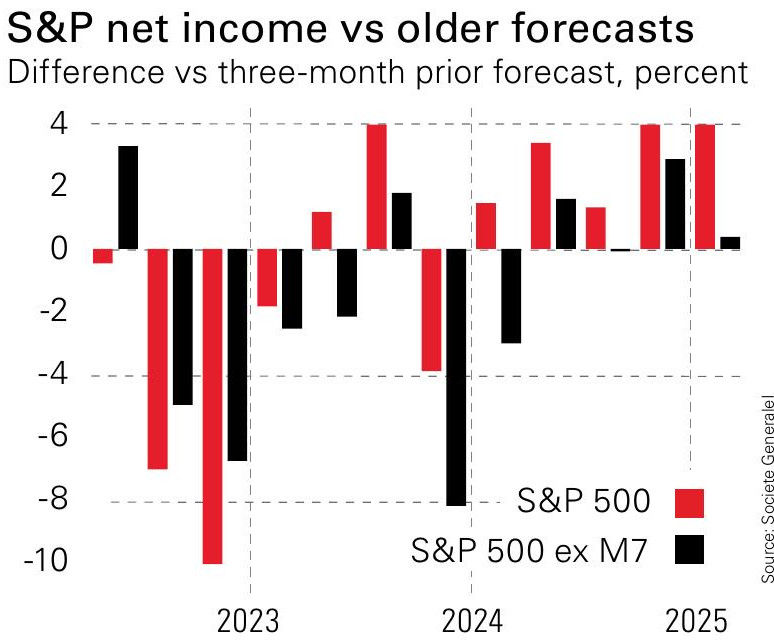

The reason is that company management – most blatantly in the US – guide analysts to lower forecasts as the reporting date approaches. They can then report earnings that beat the forecasts, and the positive surprise buoys the share price. However, if you compare reported net income for each quarter to forecasts made further in advance (three months before the quarter), “these ‘surprises’ are somewhat less impressive or not there at all”, says Andrew Lapthorne of Société Générale – see chart above.

Of course, earnings growth matters. Europe or emerging markets look better long-term value than America – but not if S&P 500 earnings keep growing much faster than the rest of the world. If the US continues to excel (which the chart suggests is increasingly a bet on the Magnificent Seven), the S&P 500 might yet come out ahead. But that has little to do with whether companies can beat short-term forecasts that they’ve carefully talked down.

So when the headlines say – as they doing right now – that more than 80% of S&P 500 companies are beating estimates, it is wise to be a bit sceptical. Does this mean that the corporate sector and the US economy is doing even better than expected; or does it suggest that the upheaval as Trump brought in his tariffs in April proved an excellent opportunity to guide down earnings aggressively and ensure a solid surprise?

This article was first published in MoneyWeek's magazine. Enjoy exclusive early access to news, opinion and analysis from our team of financial experts with a MoneyWeek subscription.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Cris Sholt Heaton is the contributing editor for MoneyWeek.

He is an investment analyst and writer who has been contributing to MoneyWeek since 2006 and was managing editor of the magazine between 2016 and 2018. He is experienced in covering international investing, believing many investors still focus too much on their home markets and that it pays to take advantage of all the opportunities the world offers.

He often writes about Asian equities, international income and global asset allocation.

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?

Early signs of the AI apocalypse?Uncertainty is rife as investors question what the impact of AI will be.

-

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industry

Reach for the stars to boost Britain's space industryopinion We can’t afford to neglect Britain's space industry. Unfortunately, the government is taking completely the wrong approach, says Matthew Lynn

-

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens

8 of the best properties for sale with beautiful kitchensThe best properties for sale with beautiful kitchens – from a Modernist house moments from the River Thames in Chiswick, to a 19th-century Italian house in Florence

-

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyond

Three key winners from the AI boom and beyondJames Harries of the Trojan Global Income Fund picks three promising stocks that transcend the hype of the AI boom

-

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth market

RTX Corporation is a strong player in a growth marketRTX Corporation’s order backlog means investors can look forward to years of rising profits

-

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of finance

Profit from MSCI – the backbone of financeAs an index provider, MSCI is a key part of the global financial system. Its shares look cheap

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China