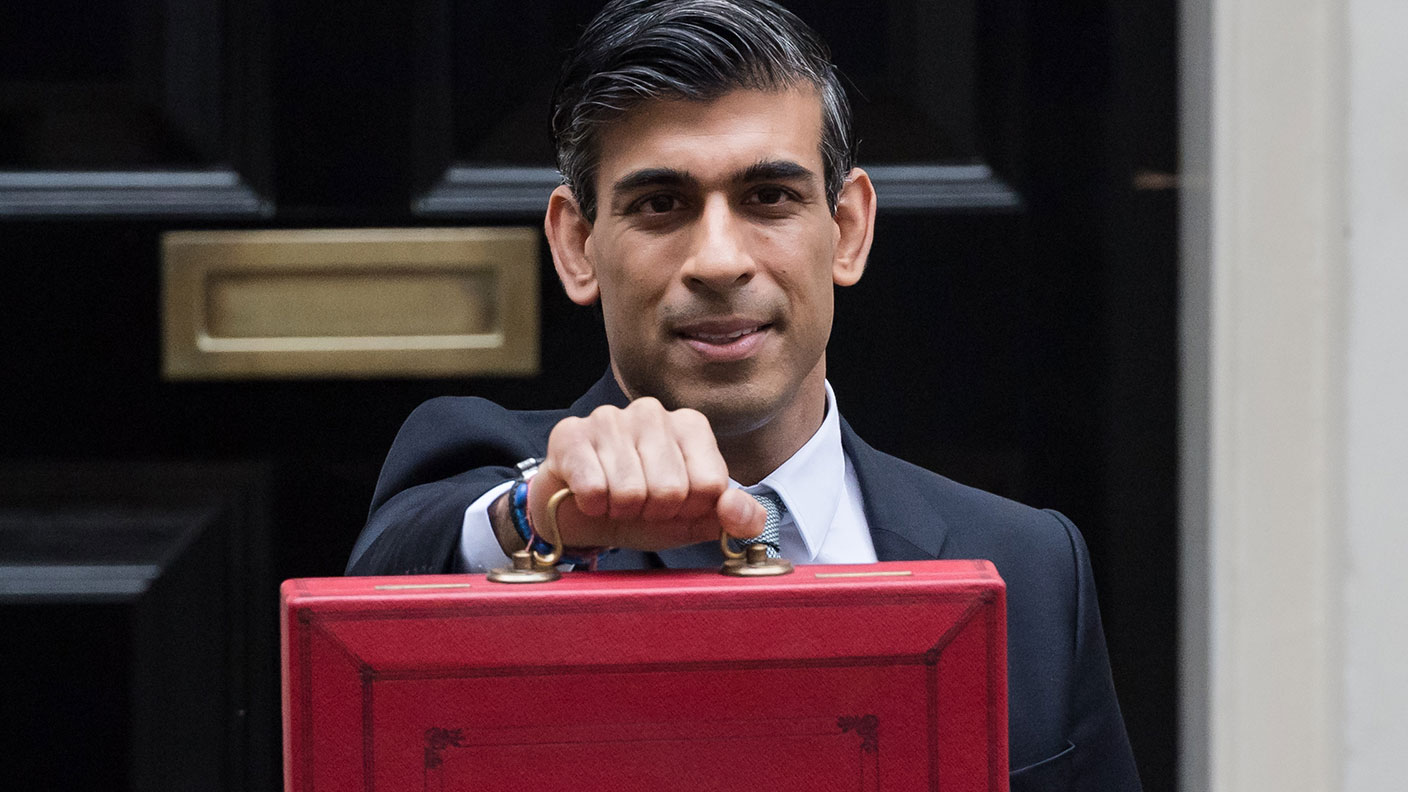

Why Rishi Sunak must tighten the government’s purse strings

We can’t turn to the printing press every time there’s a crisis. It’s time to face up to reality, says Matthew Lynn.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Twice daily

MoneyWeek

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Four times a week

Look After My Bills

Sign up to our free money-saving newsletter, filled with the latest news and expert advice to help you find the best tips and deals for managing your bills. Start saving today!

There must be moments when Rishi Sunak wonders why he ever accepted the job of chancellor. Only months after he moved into No. 11 he had the Covid-19 crisis to deal with. Now he has the war in Ukraine as well. Already he is under pressure to find a way of alleviating the inevitable pain that is going to cause for the economy.

Oil and gas prices are soaring as Russian supplies start to get cut off, and if there is a ban on importing its energy they will go a lot higher still. Food prices will start rising very soon as it becomes clear how much the world has relied on the wheat fields of Ukraine to feed itself. And all the sales lost as company after company pulls out of the Russian market and stops buying raw materials from the country will very soon feed through into output and profits.

There is a very real possibility of a quarter or two of negative growth, and at the very least there will be a slowdown. Against that backdrop, it wouldn’t be a great surprise if the government, and certainly one as free-spending as this one has proved, decided that some kind of rescue package is needed. That would be a big mistake. Here’s why.

MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

The war has made us poorer

First, we have to accept that the war has made us poorer. The vast supplies of Russian oil and gas, plus all the other raw materials it exported, as well as the vast quantities of wheat from Ukraine, lowered global prices. As all that stuff starts to disappear from the market, as with sanctions it inevitably will, then prices will be permanently higher. At some point, we will start to replace that. If Europe, including the UK, starts fracking in the same way the US has done, there will be plenty of gas available, and if we build nuclear plants as well as more wind turbines, then there will be plenty of electricity as well. If we allow gene editing we can almost certainly boost farm yields enough to replace the lost wheat and corn. But none of that is going to happen quickly and until then we will simply have to consume less. That is what happens in war.

Next, we have to get off the treadmill of permanent rescues. Over the last 15 years we spent tens of billions bailing out the financial system following the crash of 2008-2009. We spent five or ten times as much coping with the Covid-19 pandemic. And now here we are again, with a fresh crisis, and another round of demands for the government to rescue the economy. We need to get off that track. The state can’t always step in with a rescue package to magic away every downturn in the economy. Our debt levels have already soared from less than 50% of GDP before the crash to close to 100% now and are set to rise even higher over the next few years. If we keep borrowing more and more money with no plan for ever paying it back the accumulated debt will eventually crush us.

More cash will pour into defence

Finally, we will have to start spending more on defence. A new Cold War is starting and will only end when Vladimir Putin’s corrupt, autocratic regime collapses, just as the last one only ended with the fall of the Soviet Union. How long that takes remains to be seen. One point is certain, however: it will involve spending a lot more on defending ourselves. Along with the rest of Nato, the UK will need to spend more on military equipment, on stationing troops along the eastern frontier to deter aggression, and on helping the Ukrainians. None of that will be cheap. During the last Cold War the UK was spending an average of 5% of GDP on defence, compared with 2% today. If we have to find another two or three per cent of our total output to spend on our armed forces that inevitably means that we have less to spend on everything else. That includes bailing out the economy.

The very poorest among us may well need extra money to stay warm and pay for food. But we can do that through the welfare system and far more effectively than with price caps and controls for everyone. We will just have to tighten our belts and adjust – and stop expecting the chancellor to bail us out with printed cash every time there is a crisis.

Get the latest financial news, insights and expert analysis from our award-winning MoneyWeek team, to help you understand what really matters when it comes to your finances.

Matthew Lynn is a columnist for Bloomberg and writes weekly commentary syndicated in papers such as the Daily Telegraph, Die Welt, the Sydney Morning Herald, the South China Morning Post and the Miami Herald. He is also an associate editor of Spectator Business, and a regular contributor to The Spectator. Before that, he worked for the business section of the Sunday Times for ten years.

-

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%

How a ‘great view’ from your home can boost its value by 35%A house that comes with a picturesque backdrop could add tens of thousands of pounds to its asking price – but how does each region compare?

-

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?

What is a care fees annuity and how much does it cost?How we will be cared for in our later years – and how much we are willing to pay for it – are conversations best had as early as possible. One option to cover the cost is a care fees annuity. We look at the pros and cons.

-

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?

"Botched" Brexit: should Britain rejoin the EU?Brexit did not go perfectly nor disastrously. It’s not worth continuing the fight over the issue, says Julian Jessop

-

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'

'AI is the real deal – it will change our world in more ways than we can imagine'Interview Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates talks to Andrew Van Sickle about the AI bubble, the impact of tariffs on inflation and the outlook for gold and China

-

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still suffering

Tony Blair's terrible legacy sees Britain still sufferingOpinion Max King highlights ten ways in which Tony Blair's government sowed the seeds of Britain’s subsequent poor performance and many of its current problems

-

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect you

How a dovish Federal Reserve could affect youTrump’s pick for the US Federal Reserve is not so much of a yes-man as his rival, but interest rates will still come down quickly, says Cris Sholto Heaton

-

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut out

New Federal Reserve chair Kevin Warsh has his work cut outOpinion Kevin Warsh must make it clear that he, not Trump, is in charge at the Fed. If he doesn't, the US dollar and Treasury bills sell-off will start all over again

-

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald Trump

How Canada's Mark Carney is taking on Donald TrumpCanada has been in Donald Trump’s crosshairs ever since he took power and, under PM Mark Carney, is seeking strategies to cope and thrive. How’s he doing?

-

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curve

Rachel Reeves is rediscovering the Laffer curveOpinion If you keep raising taxes, at some point, you start to bring in less revenue. Rachel Reeves has shown the way, says Matthew Lynn

-

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for us

The enshittification of the internet and what it means for usWhy do transformative digital technologies start out as useful tools but then gradually get worse and worse? There is a reason for it – but is there a way out?